A more ambitious argument is that branding transcends corporate and commercial domains. Branding cheerleader Waly Olins claimed: “The influence, strategies and tactics of branding go way beyond this. Branding is playing a large and increasing part in politics, the nation, sport, culture, and the voluntary sector.” This defense is, however, its most significant indictment. Witness Trump brand vodka, steaks, casinos, and now presidencies. Even more than corporate legitimization and co-option, branding’s reconstitution of non-corporate entities as market-tamed subordinates is causing real harm. Branding has become an ideological Trojan horse, invading social and cultural realms traditionally resistant to corporate influence.

Donald Trump launching Trump Vodka in 2007. Associated Press

Graphic design relates to conflict in at least two important ways. The first is by destructively concealing it. The second is by productively revealing it.

The concealing of conflict is, of course, the camouflaging of power. It’s the distracting seduction of consumer novelty. It’s the engine of consumer culture, pumping out mental and atmospheric pollutants, hazy sceneries of shifting spectacle. Branding is now what we call these strategies of aestheticizing the concealment of social and political conflict. The global shock at Trump’s election victory is the veil tearing.

Although utterly superficial and cynical, branding is actually more significant than even its cheerleaders claim. Everyone now has opinions about branding, and everything—from your haircut to your handwriting—is spoken about in terms of branding. The ubiquity of the word is a candid index of neoliberal victories. Is there a corner of our culture still untainted by branding? Branding is a symptom of consumer capitalism’s failings, but not only a symptom. Branding has now breached the last barriers to advertising’s voracious environmental and psychological penetration. The heretofore stubborn evidence of coercive corporate power, of real social and political antagonisms, is hereafter elegantly “branded” away. This is design’s complicity in maintaining social inequity, disadvantage, and atomization. The designer is daily obscuring and reinforcing hierarchies of privilege and class division.

But these are just the obvious consequences of omnipresent branding. Less obvious is its colonization of social organizations, non-profits, public institutions, and geographical territories, so that even those entities with explicitly independent or oppositional agendas are displaced and transformed.

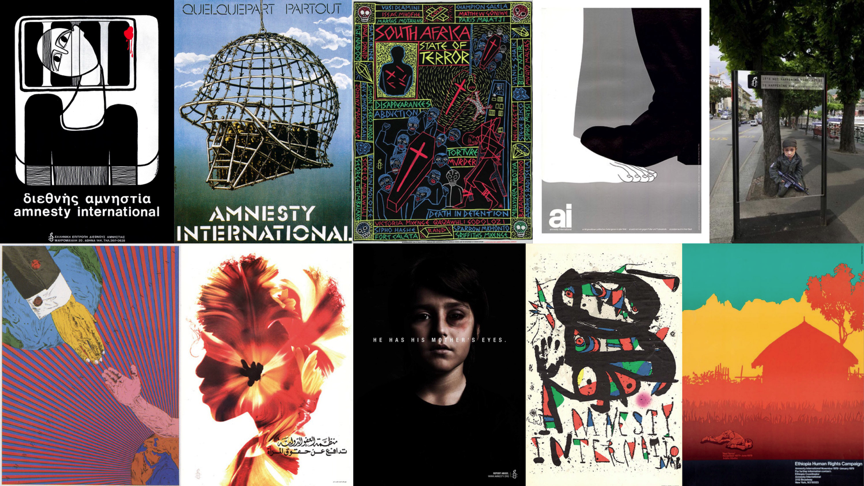

Here’s a fairly random selection of 20 Amnesty International posters. The first half were created prior to 2008, and the second half after 2008, when Wolf Olins implemented a global branding campaign.

Amnesty posters pre-2008 Wolff Olins’ global rebrand. Various designers.

Amnesty posters post-2008 Wolff Olins’ global rebrand. Various designers.

Isn’t this is the difference between expressive human communication (for a human rights organization, after all) and corporate messaging? The difference between diverse, imaginative, visual provocations, and an emasculated voice, both formally and rhetorically? Is this not the waning from illustrative to photographic, from colorfully carefree to carefully approved, from compositionally fluid to rigid, symbolic to indexical, metaphoric to concrete, from unexpected to predictable? My point is not that all the pre-branding instances here are great and all the branded ones bad. The real problem is that this general devolution of communication isn’t likely to stop at the aesthetic.

It may not be possible to understand how this change affects an organization like Amnesty International—to sift the communicative and constitutional consequences. But insisting that the results are all positive is not honest. While I’m not claiming that there’s no room for consistency in visual identity design, isn’t the uncritical application of any communications methodology asking for trouble? To me, these posters illustrate that the recent semantic shift from terms like “design” and “visual identity” to “branding” was necessary to define an increasingly dehumanizing process. The historical application of the term “branding” from livestock, slave, prisoner, and product identification to the expression of personal values has a consistent trajectory.

Ask anyone who works in a public university, for example, how deep the bureaucratic agendas of corporate marketing have seeped into the fabric of their institution. This communication is not just “consumer facing;” it is internally absorbed and manifested at best as a demoralized academic culture, and at worst as a debased common good. The cynical advertisements become hallowed mission-statements. And increasingly, the reputational contrivance and competitiveness of branding in the public university sector does not merely reflect its gradually corporatized culture—it is also fueling the change. Here in Brisbane, higher learning institutions are all “Universities for the Real World” (so goes a prominent institution’s brand statement). Perhaps “Universities for the Perverse Whims of the Marketplace” just lacked a little poetry? For students, that’s the reality of “reducing the worth of a thing to the price of the thing, and the worth of a person to the wealth of the person… of defining your value exclusively in terms of your activity in the marketplace” as William Deresiewicz recently put it. And for staff, it’s the real world of pressurized and precarious contract employment, bureaucratic barriers, and impossible workloads.

The mindless conformity to branding principles is transposing fundamental priorities. Standards for appropriate corporate communication infiltrate public institutions, democratically elected governments, nation-states, geographical regions, non-profit organizations, and other social enterprises whose very missions are to resist homogenizing values. Branding is regulating critical agency and subtly directing ethos.

Of course, these brandings are already reflections, collective representations, and myths that have been inverted, overturning culture into nature so that, as Roland Barthes wrote, “what is nothing but a product of class division and its moral, cultural and aesthetic consequences is presented as […] Common Sense, the Norm, Right Reason and General Opinion […]”

These myths have long made it unfashionable and impolite to even mention class. Manufacturing has mostly migrated out of developed countries, but because we can't see it, do we somehow think it has vanished, and do we assume that class struggle has vanished also? And did we expect the inequality—experienced so acutely by those left behind, and so lethally exploited by Trump in the US heartland—to just fade away?

São Paulo, Brazil, is an example of how branding has veiled social antagonisms, both literally and figuratively. São Paulo became famous as the first city in the world to ban what the industry calls “out of home” advertising, the commercial billboards and signage that blanket most cities. Removing these signs helped reveal the stark poverty of the favelas (urban slums). “Debranding” São Paulo unmasked the divide between the promoted aspirations of consumer luxury and the reality of rampant disadvantage. It visually confessed class conflict.

The Paraisópolis favela next to the gated Morumbi complexes. Image by Tuca Vieira.

So if design is complicit in these processes, how can it be redeemed? With all our skills and creativity, we can highlight what is airbrushed away in the name of marketing. We can render alternatives. We can do much to change the meaning of things, and therefore change the world and our role in it. This is what design theorist Tony Fry calls “recoding,” an assumption that a total transformation of the material world towards sustainability is not possible, but that recreating meaning is. Even if designers’ critical responses are sometimes tiny gestures against a greater force of commercial manipulation, doing nothing is active acquiescence.

Design is unavoidably an art of conflict. It inevitably attempts to organize conflicting social relations in time and space, just as Daniel Bensaid described politics as “an art of shifting the lines (of changing the balance of forces) and of breaking apart the march of time.” We are entering a crisis of civilization where, as Bensaid wrote, “the essential thing is to give the non-fatal side of history its proper opportunity.” This opportunity will require us to design democratic spaces for productive resistance, and for these realms to repel the ideological weapons of the market, among them the petty, lethal enchantments of branding.

Read on: Against Branding: Part 2 — Design and Happiness.

Based on talks given at the Asia Pacific Design Library’s lecture series.