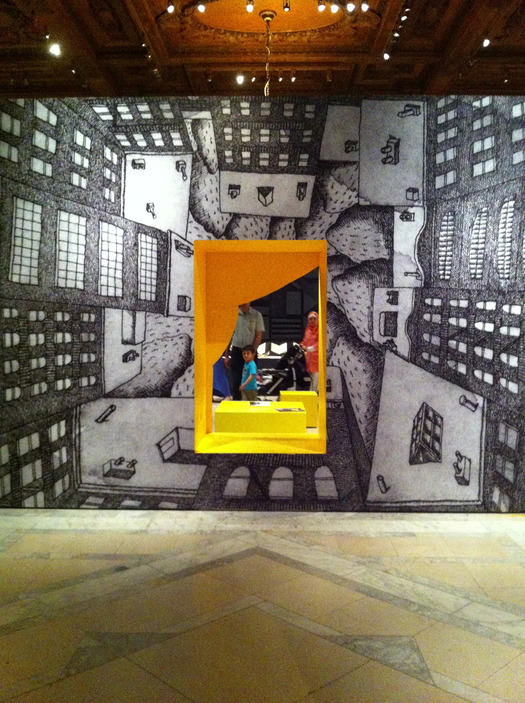

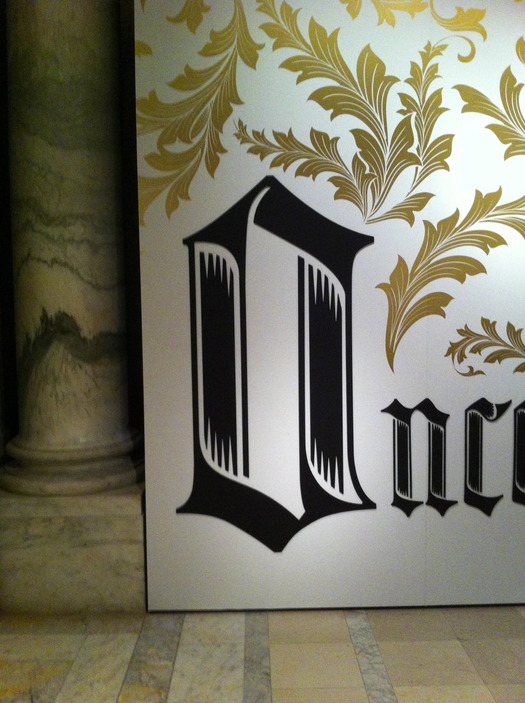

"The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter," at the New York Public Library (thru March 23). Designed by Pure+Applied.

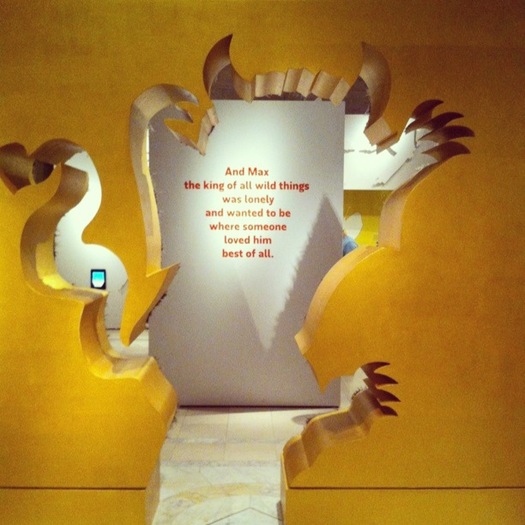

Were you a child? Did you read books? Then you will surely find the New York Public Library's new exhibition, "The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter," a portal back in time. Walking around the show, curated by Leonard S. Marcus and designed by Pure+Applied, can be a little like showing up at a party and finding it populated by elementary-school friends. There is Ferdinand in the corner, just smelling the flowers. Here is Alice in the hall: she's eaten something that doesn't agree with her, as her neck has stretched to giraffe proportions. You might think twice about heading for the kitchen, as a Wild Thing has gotten there first. If you actually are a child, you could just sit in the exhibition's foyer, watching three screens displaying pictures representing A, B, and C in their seemingly infinite variety. There's more to the exhibition than that, but from a visual perspective it is so refreshing to see a show on design for children with rich, imaginative scenery, interactive elements on screens and on shelves, and an educational agenda that can be accessed for 15 minutes or two hours. The theatricality inherent in exhibitions has not been forgotten or suppressed in order to prove the seriousness of children's books as literature. (The New York Times review, by Edward Rothstein, is here.)

For it is a serious show, one which opens with examples of writings on childhood from theology, philosophy and psychology. Deciding what children should read reveals larger differences about how and what kind of adults we want them to become. Does early exposure to the Bible make better Christians, as Cotton Mather believed? Or would they be better off reading "the book of Nature," a.k.a. experience, as Jean-Jacques Rouseeau argued. Or do they just need to learn to read, by whatever path delights them, per John Locke? Locke thought Aesop's Fables provided the right combination of entertainment and instruction. I recall my brother picking his way first through comic books and then more fluently through Stephen King. My parents didn't really understand, but they were happy he was turning the pages, and therefore happy to buy him paperback after paperback.

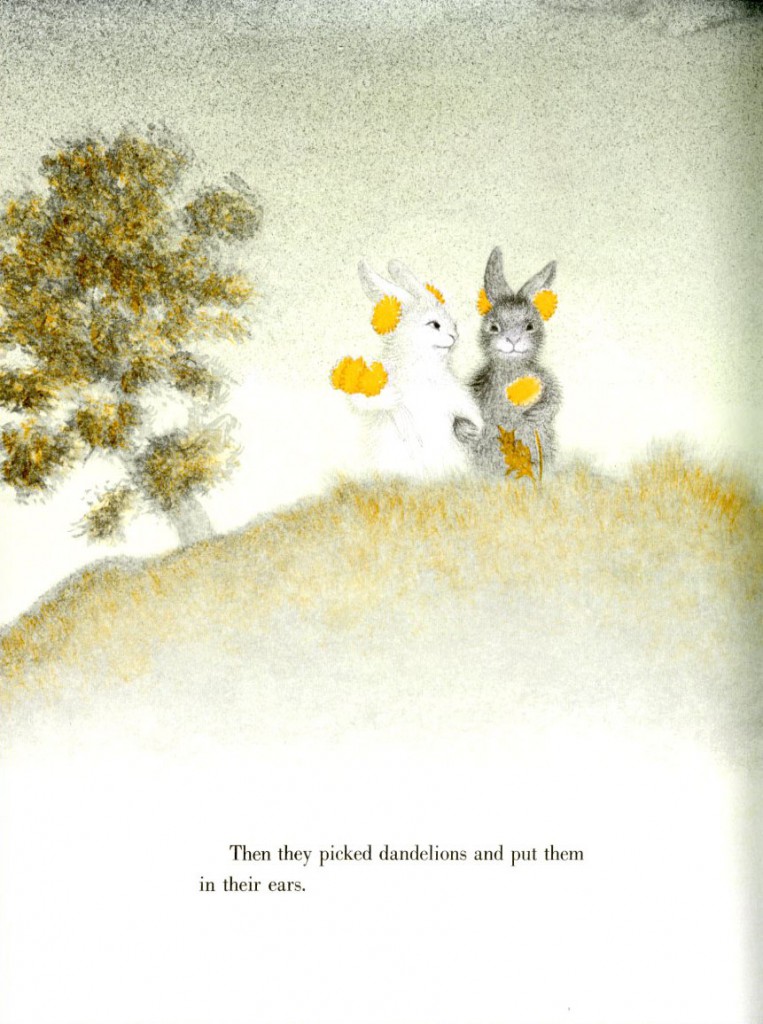

From The Rabbits' Wedding (1958), written and illustrated by Garth Williams.

"The ABC of It" moves forward and backward in time in each thematic section, revealing just how contested the territory of children and reading remains. A darkened hallway offers a chronology of once-banned books, with controversial passages helpfully highlighted. There is Adventures of Huckelberry Finn and Judy Blume, but also a picture book called The Rabbits' Wedding (1958) by Garth Williams, best known for illustrating E.B. White and Laura Ingalls Wilder. The controversy of the rabbits' wedding seems particularly apposite to our present moment, when an interracial family in a Cheerios ad generated controversy. Williams drew a black bunny and a white bunny getting married, and the book was removed from the Alabama state library system, accused of being hidden propaganda for interracial love.

The exhibition moves from pedagogy to fantasy, from children's books as a business (the Stratemeyer syndicate behind Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, and other now-dated escapades) to children's books as an art (Eric Carle's color studies). A few sections seemed of particular interest to designers. First, a number of original sketches of famous animals: Alice and her flamingo by John Tenniel, an early version of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter. Second, modernist children's books from a broad variety of sources. These include the Russian robot tale Topotun and the Book and In My Mother's House, a collection of Pueblo Indian poems created by Ann Nolan Clark, a white educator on a reservation, and illustrated by Velino Herrera. Did you know Edward Steichen photographed a children's book? I did not: but was drawn to the elegant still life of blocks from The First Picture Book.

Last in the gallery, but certainly not least, is a wonderfully-curated section of books about New York, including Faith Ringgold's striking Tar Beach and Sydney Taylor's All-of-a-Kind Family (a childhood favorite of my own). Lewis Hine's Men at Work, shown there, was originally published as a children's book. As Marcus writes on the label,

The editor, Macmillan's Louise Seaman Bechtel, was an ardent champion of the Bank Street 'here and now' approach to realism in children's literature... Bechtel believed that an eight-year-old would thrill to see real people operating modern machinery and building a skyscraper.I know my five-year-old would. I have to admit that, by the later sections of "The ABC of It" I began to use the exhibit as a future shopping list, gathering ideas for birthdays and Christmases off the beaten or franchised path. I've re-bought most of my early library for my children, and I have found that Make Way for Ducklings and Mary Poppins (also in the exhibition) still have the power to charm. If a book works for children, it will work for children born in any decade. It will also work for their parents, decades later. Adult preoccupations and projections change, but children still have to learn their ABCs, whether from robots, magical nannies or alligators.