Turn left as you enter the sprawling warehouse-style home of Liberty Auctions, in Pembroke, Georgia, if you want to examine the array of furniture and household goods and charismatic doodads judged to have enough potential value that they are worth auctioning piece by piece.

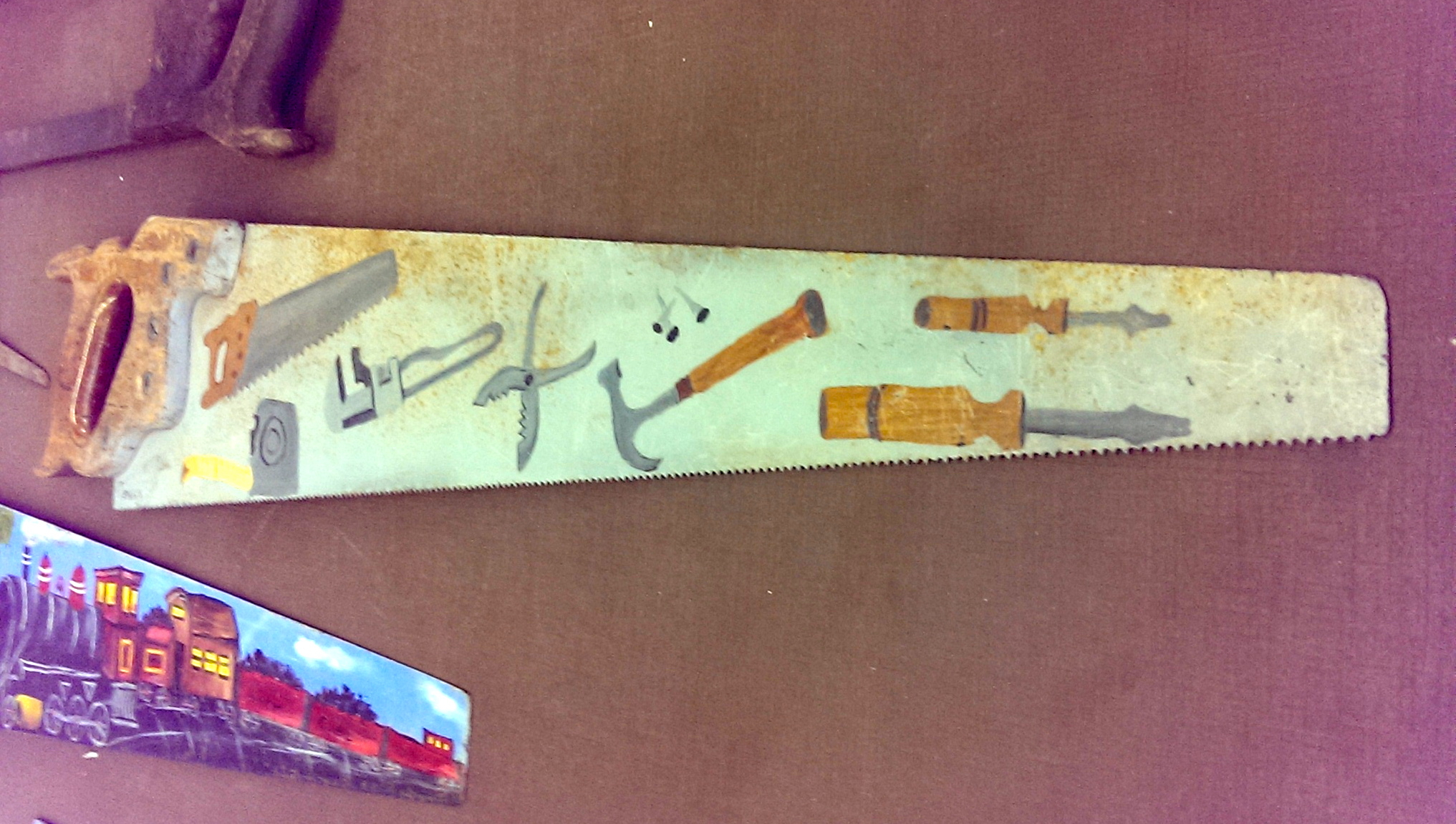

But head right for what I find more appealing: dozens of tables arranged in 50-foot-long rows, each completely strewn with objects. Uncountable things are stacked, crammed in boxes, leaning against each other.

It’s a carnival of stuff, and before the night is over, every bit of it will be gone.

Every thing here used to mean something to someone. But that's about to end. Whatever past these objects were a part of will be erased; whatever defined their value before tonight will be replaced — by some new value determined by the vagaries of whoever is here tonight.

The tables will be empty. Whatever lives these things used to have … will conclude.

Liberty Auctions offers “estates, household goods, defaulted storage and more items,” every Thursday night, starting at 5 p.m. The auctions — for much of the night, there are two running simultaneously — go to 11 p.m. or later. In short, the ritual lasts for as long it takes to clear this massive space of the week’s material haul.

I’d been to estate sales, auctions, and all manner of garage/yard/stoop selling events. But I’d never been to anything like Liberty Auctions. E came upon this place in the course of a furniture hunt, came away fascinated at the scale and the scene, and insisted I come see it.

I think she has been to four of these events; I’ve come along twice. We make a night of it, as many other attendees do. You see familiar faces; there are regulars. There is even a surprisingly solid sit-down eatery embedded in the space, serving up burgers and chicken sandwiches and Cokes and popcorn. It’s fun. For someone interested the ways the lives of things intersect with commerce, Liberty Auctions is a great place to be.

I can’t say I have a firm grasp on Liberty Auctions as a business, so I’m not sure how many estates or defaulted storage units are represented by those long tables of junk.

What I’m fascinated by, really, is the quietly ruthless nature of the proceedings.

An auctioneer climbs a rolling stepladder. Potential bidders and a handful of other Liberty employees crowd around. It’s a “pick lot”-style auction, meaning maybe-buyers signal what interests them, and the bidding begins.

Sometimes that bidding is focused on a specific object — a lamp, a vacuum cleaner.

Sometimes the auctioneer isn’t clear on the object specifics — “A router? Some kind of power tool.” Or even: “I don’t know what that is.”

And often the bidding is focused on a vaguely defined bunch of objects:

“Basket of maps.”

“Drawer-full of wrenches.”

“Pile of records.”

“Box-full of kitchen stuff.”

“Stack of bibles.”

(I’m not making that up: I saw two “stacks of bibles,” literally, auctioned off for a few bucks each.)

The phrases are poetic enough. But the auctioneer’s deadpan ambivalence repeatedly turns me into the one guy standing at the junk table wearing an idiotic grin of delight.

The absolute highlight, to me, of these pick-lot affairs, is the “boxfull.” It’s a box, full ... of something.

The details, that nomenclature implies, aren’t worth getting into. Whatever the box may be full of, you get it all. I am constantly tempted to bid on a “boxfull,” just to see what I’d end up with.

Eventually every thing or boxfull that anybody wants to bid on has sold. At the point, bids are taken for everything left on the table, collectively.

Thirty pounds of completely random objects can go for five bucks.

It’s really a poignant moment in the biography of a thing: reduced to story-less, indifferent anonymity in a crowd of objects — the precise opposite of a glorious life climaxing with a triumphant turn on Antiques Roadshow,let’s say.

I would love to know what happens next to material in these boxfulls, these random collections of every thing left over on a row of tables. Some of it, I assume, is headed for landfill.

But the rest presumably finds its way back into the ecosystem of objects and money and (maybe?) meaning, via flea markets or eBay and the like. Surely the buyers will comb their hauls hoping there is treasure lurking.

And maybe there is. Things confront an ending at Liberty Auctions. But also, maybe, a beginning.