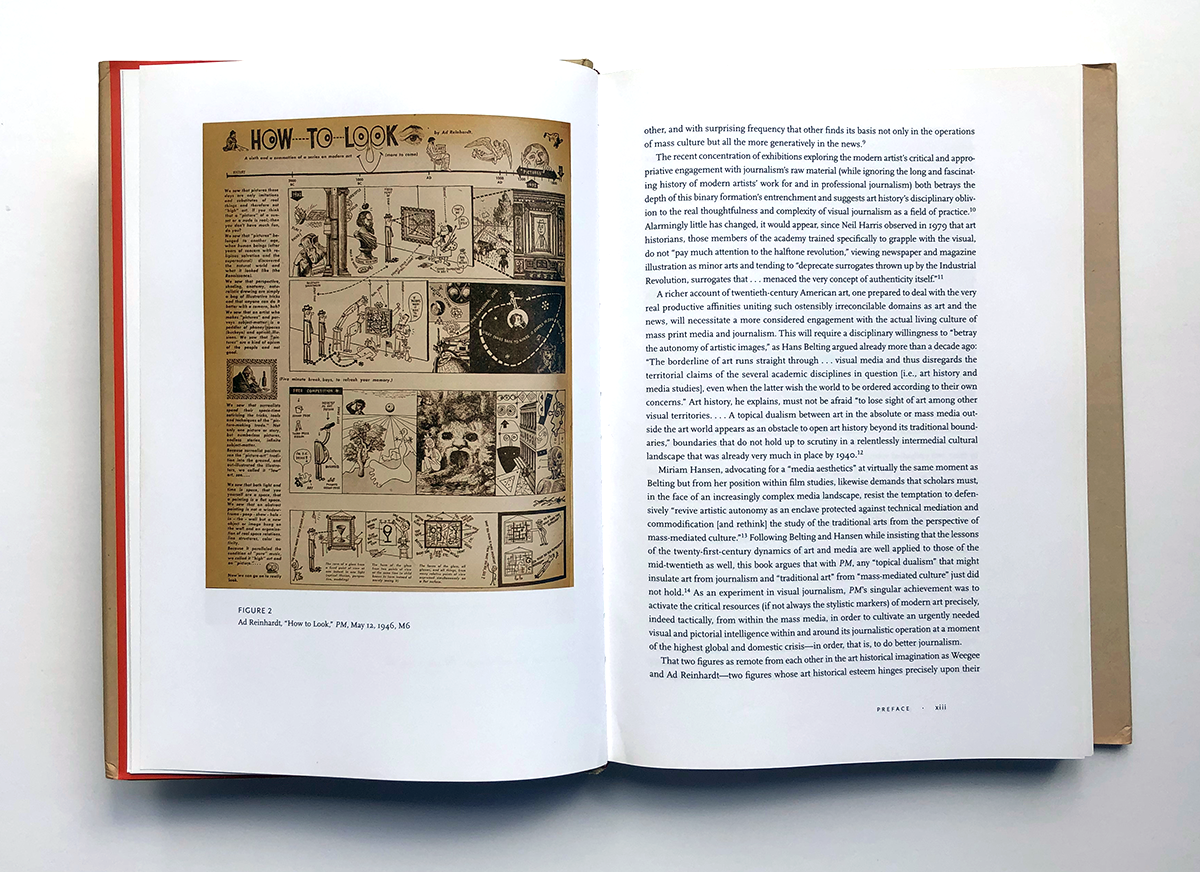

Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from Chapter Two of the book Artist as Reporter: Weegee, Ad Reinhardt, and the PM News Picture, by Jason Hill. The chapter, entitled "Drawing on Newsprint," considers the 1940s New York daily newspaper PM's experiment with the then already "lost art" of sketch reporting.

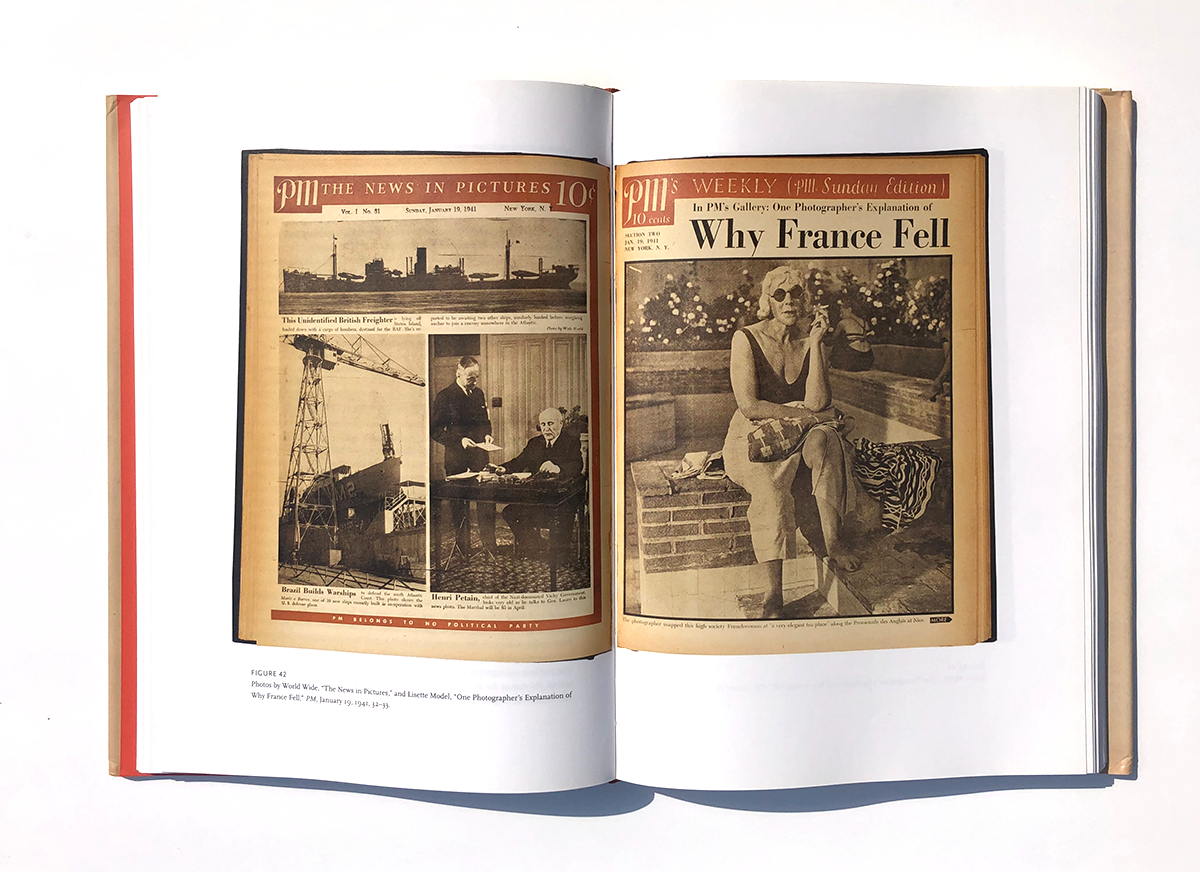

The 1940s New York daily tabloid PM invested as heavily in high-end production apparatus as in talent, and early staff memos and publicity brag of PM using heavier, more expensive paper stock, finer halftone screens, and a newly developed “frozen ink” printing process enabling sharper and faster (i.e., less smudge-prone) visuals. All money spent in the pursuit of reproductions closer in quality to the weekly and monthly picture magazines than to PM’s reprographically wretched competitor dailies—and all yielding photographs whose mediating work was that much harder to see for it. The fruit of this investment pervades the tabloid, and the briefest perusal of PM’s first year yields a functional anthology of canonical midcentury New York photography by the likes of Berenice Abbott, Margaret Bourke-White, Sid Grossman, Helen Levitt, Lisette Model, and Weegee, all lavishly printed and elegantly staged as a matter of daily journalistic routine.

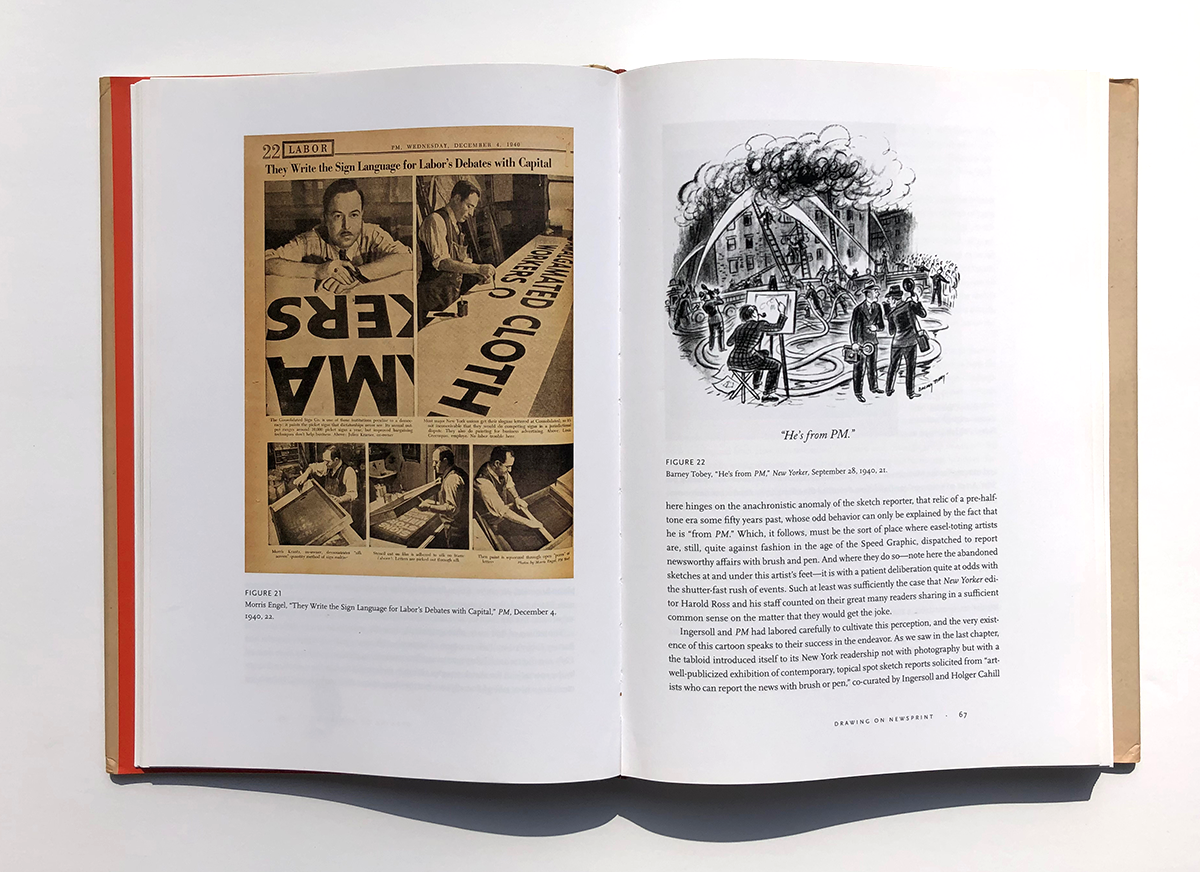

This would seem to speak to an unambiguous confidence in photography, but the photographs themselves often tell another story. A single, unheralded and (for PM) procedurally unremarkable essay photographed by staffer Morris Engel, published on Wednesday, December 4, 1940, conveys the productively doubtful character of this tabloid’s photographic activity in its early goings. Photographed for editor James Wechsler’s daily “Labor” section, Engel’s feature takes as its subject not some murder or conflagration such as one might expect from tabloid journalism, but instead the local Consolidated Sign Company, “one of those institutions peculiar to a democracy,” according to PM’s caption, that “paints the picket signs that dictatorships never see.” Under a headline declaring that “they write the sign language for labor’s debates with capital,” Engel and PM train their news-making machinery on the small company’s staff in order to relate the artisanal particulars of their infrastructural contribution to the messy democratic visual culture of labor and protest.

In its pairing of Engel’s unmistakable photographic formal intelligence and the pressroom printer’s almost flashy reprographic fidelity in the service of a smartly laid out tribute to organized labor in its own graphic methods and priorities, the brief essay crisply encapsulates PM’s thematic and formal priorities. It activates good photographic (productive and reprographic) practice toward the ends of foregrounding, by photo-mechanical reference to the Consolidated Company’s more plainly artisanal modes of visual argument, the means by which a sound visual politics might proceed. PM justly enjoys a formidable position in the photo-historical literature. But to further indulge the temptation and continue to engage with PM through the photographic lens alone will be to distort matters too much. PM, as we’ve seen, worked hard to carve out rather a different pictorial reputation for itself.

Something of that early, photographically agnostic reputation can be gathered from Barney Tobey’s New Yorker cartoon of September 28, 1940, published three months into PM’s run. Tobey’s cartoon offers two veteran picture-snatchers more dazzled by the spectacle of the sketch reporter sitting in their midst than by the sensational apartment fire they have been called out to record. Tobey’s gag here hinges on the anachronistic anomaly of the sketch reporter, that relic of a pre-halftone era then some fifty years past, whose odd behavior can only be explained by the fact that he is “from PM.” Which, it follows, must be the sort of place where easel-toting artists are, still, quite against fashion in the age of the Speed Graphic, dispatched to report newsworthy affairs with brush and pen. And where they do so—note the abandoned sketches under this artist’s feet—it is with a patient deliberation quite at odds with the shutter-fast rush of events. Such at least was sufficiently the case that New Yorker editor Harold Ross and his staff counted on their great many readers sharing in a sufficient common sense on the matter that they would get the joke.

Filling its pages with artists’ reports, PM made a sound if often dully practical case for the sketch reporters’ contemporary relevance in the wake of their otherwise-entrenched displacement at the hands the faster and more economical press photographers. Much of this artists’ reporting was presented with a clear and unimpeachable journalistic purpose, granting to vision events that, due to extra-journalistic constraints of space, time, regulation, or coercion, remained strictly unavailable to the press photographer. William Sharp’s sketch reporting offered a journalistic workaround where legal and institutional regulations prohibited camera access to the newsworthy scene. That Sharp frequently supplied courtroom sketch reporting to the tabloid is to be expected: the courtroom sketch has been routine in post-halftone journalism since the American Bar Association and Congress banned cameras from courtrooms in the late 1930s.

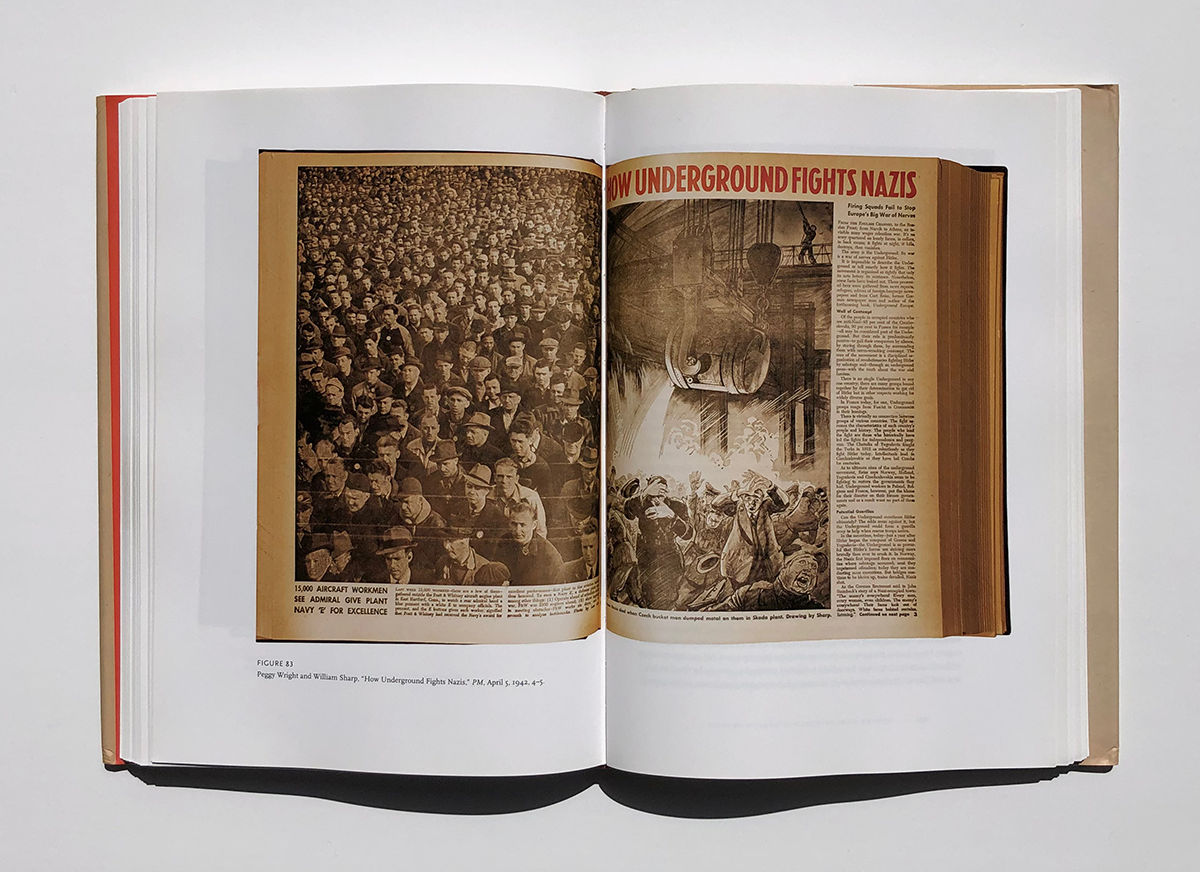

Sharp’s sketch reporting for PM took on a more urgent cast with its treatment of the Nazi regime, which the veteran Berlin press artist had fled following a terrifying encounter with Joseph Goebbels in 1934, after the discovery by Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry of Sharp’s pseudonymous anti-Nazi press illustrations. Over seven days in October 1940, PM countered that ministry’s tight control over media representations by publishing dozens of pages from a “smuggled sketchbook” drawn by Sharp in the early 1930s. Sharp’s sketchbook catalogued both atrocities witnessed firsthand and, through artful invention, the less empirically visible atmosphere of terror accompanying the Nazis’ rise to power during those years. Sharp’s drawings—including one of a Czech saboteur dumping molten steel on touring officers at the Nazi-controlled Skoda munitions plant—depict events whose description passed only through underground channels and for which no photographic evidence was available.

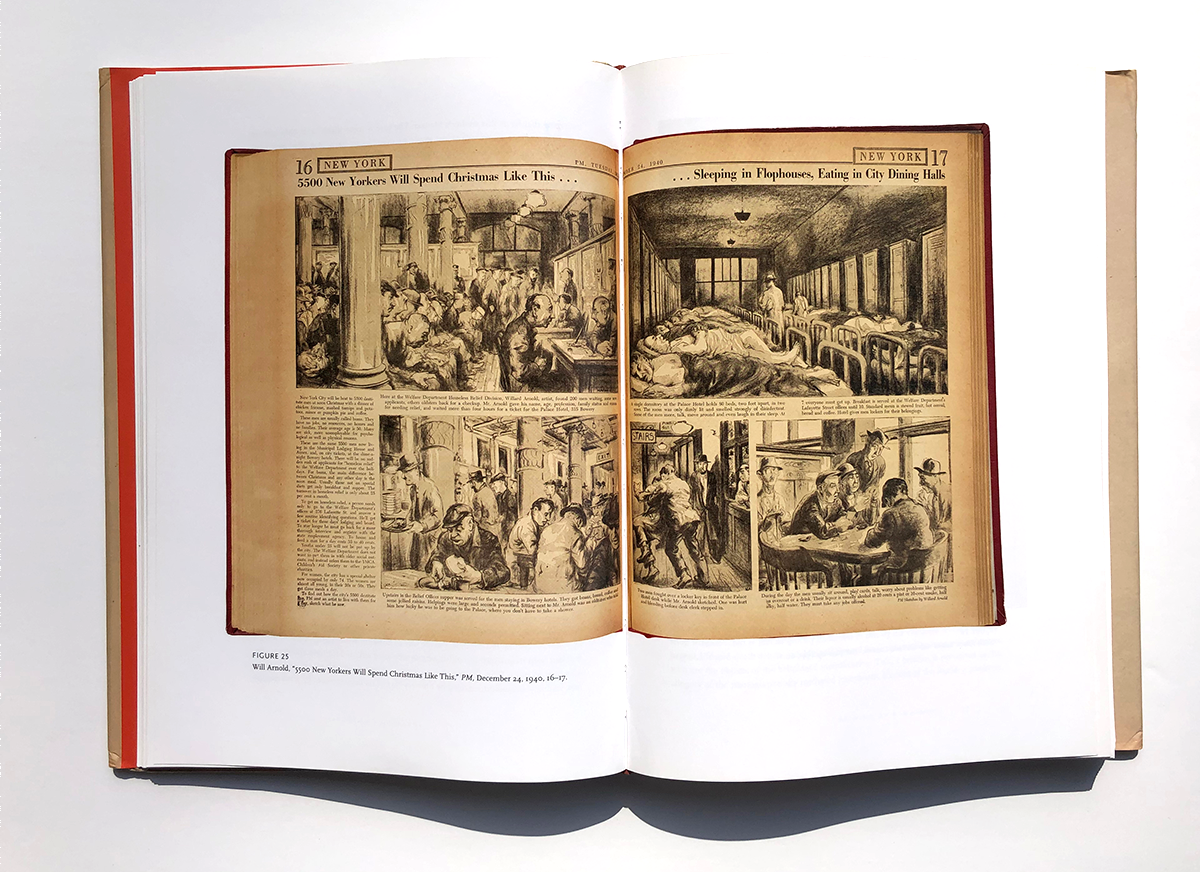

Just as typical for PM was the rather more surprising tactic of assigning artists to report on local and topical circumstances perfectly suitable and available to photography. Such reports were ubiquitous in PM’s reporting in its first years, and, like Will Arnold’s virtuosic December 24, 1940, report on the Christmas holiday travails of New York’s Bowery homeless population, they are transparently as much a record of their depicted subject matter as they are proof of their makers’ sustained transactional engagement with the “news” they would report. Amid its moment’s freshly consolidated discourse of press-photographic objectivity and instantaneity, Arnold’s was an ungainly, impractical kind of proof that could only have been measured against that seemingly surer kind promised by the camera—so much slower than photography, and so much weaker in its evidentiary claims. PM’s doubt about photography and corollary faith in the sketch report hinged on something more than the weak notion that one medium or the other enjoyed, by some essential virtue, a stronger purchase on its pictured world. But it did in one important sense hinge on an essence, something difficult to see because it was still more fundamental to photography as a medium, and something PM was very much at pains to make visible within its press-photographic practice: photography’s, and more emphatically press photography’s, built-in invisibility as a mediating apparatus.

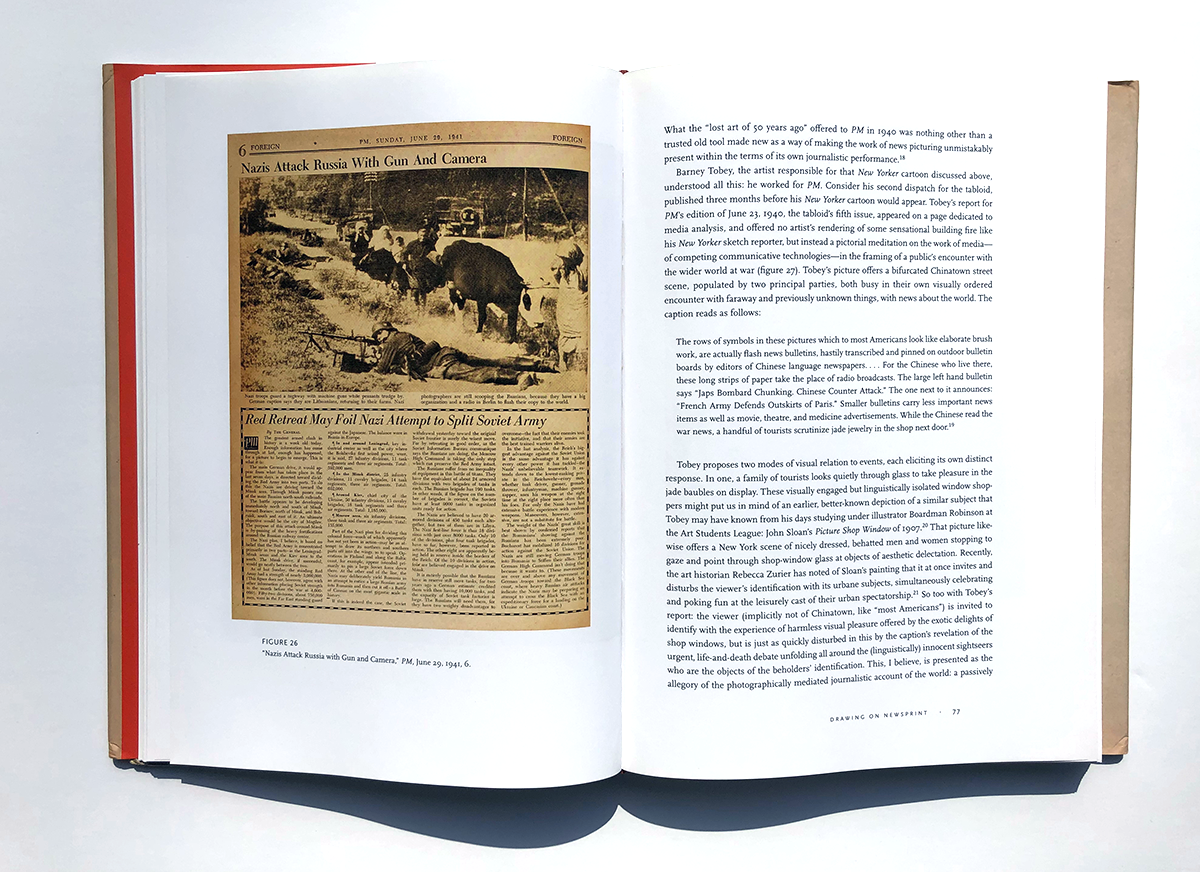

On occasion PM’s project of engendering this visibility—of making the invisible work of photographic world-making available to sight—was flagged photographically. Consider a photographic report of June 29, 1941: “Nazis,” PM’s bold headline declares to be the news here, “Attack Russia with Gun and Camera.”. It is a confusing claim, weighed against the evidence presented in the picture. A German machine-gunner is plain to see, but the presence of a camera is an altogether more obscure matter. There is a small box at this soldier’s elbow, to be sure, but this photograph’s legibility has suffered too much in its wired transmission to allow any clear reading of its function. Two discs protrude just enough from its depressed face to cast slim crescent shadows, permitting a plausible reading of this box as some kind of military-issue twin-reflex camera. But the box reads just as easily, and at least as plausibly, as a munitions magazine that feeds this soldier’s Mauser. The case is undecidable, and PM’s caption further complicates our sense of just where we might locate the activity of photography in the Nazi aggression here: “Nazi troops guard a highway with machine guns while peasants trudge by. German caption says they are Lithuanians, returning to their farms. Nazi photographers are still scooping the Russians, because they have a big organization and a radio in Berlin to flash their copy to the world.”

PM’s caption directs its readers’ attention less toward that ambiguous box nestled beside the Nazi gunner than to the camera that cannot be seen in this or any picture. PM, in its judicious conflation of two weapons of war, walks its readers’ attentive gaze some meters back from that uncertain box and toward the certain camera behind the photograph presented here, toward the activity of the man who wants us to see this picture and to believe in the totality of its discourse, and further, toward the whole of the photographic apparatus of wire services and strategy and information control into which that same camera is instrumentally woven. This latter, this invisible and therefore doubly dangerous camera work, this photography that cannot be seen in the photograph, is the picturing work that PM labored to grant to its readers’ vision.

This was and is difficult work. The invisibility of the photographer in the photographic image, and particularly in the journalistic photographic image, supports the double myth that photography has not in some way produced the object of its capture, and that the photographic image is not intrinsically a politically motivated instrument. For PM, the activation of the artist’s sketch report was the favored instrument for disrupting this model of press photographic sophistry, for disrupting a press photographic system founded on the invisibility of its work. What PM’s editors understood was that photography’s journalistic transparency—its invisibility—was not natural but cultural, a made way of thinking about a given class of images that had been naturalized through a long synthesis of editorial framing and sheer, generation-long ubiquity. What the once but no longer ubiquitous sketch report offered was a new visibility-as-medium enabled by the very fact of its displacement by photography. What the “lost art of 50 years ago” offered to PM in 1940 was nothing other than a trusted old tool made new as a way of making the work of news picturing unmistakably present within the terms of its own journalistic performance.