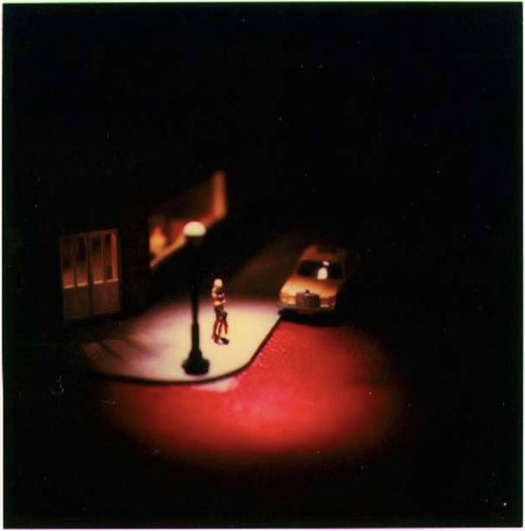

Untitled from the series Modern Romance,1983-1985, SX-70 Polaroid, 4.25 x 3.25 inches © David Levinthal

Editor’s Note: This is the sixth installment of an eight-part series from Adam Harrison Levy about designers, artists and cooking. To see all the installments, click here.

Don't be fooled by David Levinthal's taste in food. His recipes of choice, his mother's brisket and her chocolate roll, might seem nostalgic and safe, harkening back to an idyll of a 1950’s childhood. But just like the photography that he is known for, darker shadows lurk.

“One of the things about not being a cook is that you are less fearful of experimenting,” he says impishly. As a photographer, Levinthal is known as someone who fearlessly explores the disturbing realm where seemingly innocent objects ― the toys and miniature figurines of childhood ― encounter adult themes and obsessions.

In his Modern Romance series, film noir haunts the defocused images of women silhouetted under street lamps and men who linger in the shadows of darkened rooms. He constructs a world of loss and isolation out of innocence.

The same with food ― he takes the commonplace and gives it a peculiar and unsettling twist. When he moved east from California (where he was raised) to attend graduate school at MIT, his mother wrote out seven recipes for him on 3x5 cards. One of those recipes was for a boneless chicken breast glazed with soy, honey and gin. For Levinthal, the soy sauce and the honey “was sort of like the glue that held everything together,” which is the perfectly sticky descriptive language for someone who spent hours constructing miniature worlds in order to photograph them. Levinthal, following his mother's instructions, would assemble all the ingredients together and then cook them for two hours. It was one of his graduate school standbys.

Some years later he was living in New York. He was successfully supporting himself as a photographer by innovatively using a large format Polaroid camera to shoot his miniature worlds. One night he found himself with a leftover bottle of excellent champagne. “You really can't save champagne, so I decided, I'm going to use it. But what's going to be the glue that holds it all together? So I used Dijon mustard. And lo and behold the champagne and the Dijon mustard made this great glaze” which is an excellent example of an artist/cook making creative decisions in the kitchen with what he had at hand. But he then adds a detail that gives us a glimpse, in a melancholy Levinthal type of way, into his existence at that time: “for several nights in a row I ate this chicken with some rice and peas.”

As a child growing up in sun lit California, Levinthal had been drawn to the darker world of detective fiction, graphic novels and the secrecy of small spaces. His family was overwhelmingly accomplished and successful ― in academia, in physics, in business. Nobel Laureates would drop in for drinks at his parents' house and stay for dinner. He conformed to the high expectations of his parents ― he did well at school, even skipping a grade ― but he was always “the smallest and youngest, always out of step. No one should have to suffer that.” He was also the conciliator between an often explosive father and an emotionally reserved mother. He became sick. At the age of 19 he developed colitis, an inflammation of the large intestines, which was accompanied by a spastic colon: “a very unsexy disease.” While at Stanford, he memorized the location of every bathroom on campus, just in case he had an emergency. The veneer of successful normality was stained with darker concerns.

It's interesting, then, that one of his chosen recipes is his mother's brisket. It seems like a tribute to the sunny, optimistic, abundant 1950s. The dish is endearingly of its time, almost like a pop cultural reference, an image of cornucopia sitting on a table of plenitude.

Levinthal is married now and he has a young son. His studio loft radiates a feeling of tumultuous domesticity. But when he lived alone he would often cook one big batch of food on the weekends, with the intention that it would last through most of the following week. Brisket is perfect for this kind of utility eating.

In his mother's version, the sauce would turn redder the longer the meat was cooked, but since Levinthal favored a browner sauce he came up with his own variation. “You take onions and you brown them. I had this beautiful pot that had been my grandmother's ― one of these heavy thick pots that was shaped almost like a brisket. I would brown the onions ― actually, I'd burn them a little bit. And then turn off the heat ― you are doing this on the stove top ― and put in the brisket and it kind of sizzles a little bit, and then on top you pour a bottle of Heinz chili sauce. You then take some of the onions and put them on top of the brisket and you stick the whole thing in the oven at 350 degrees.”

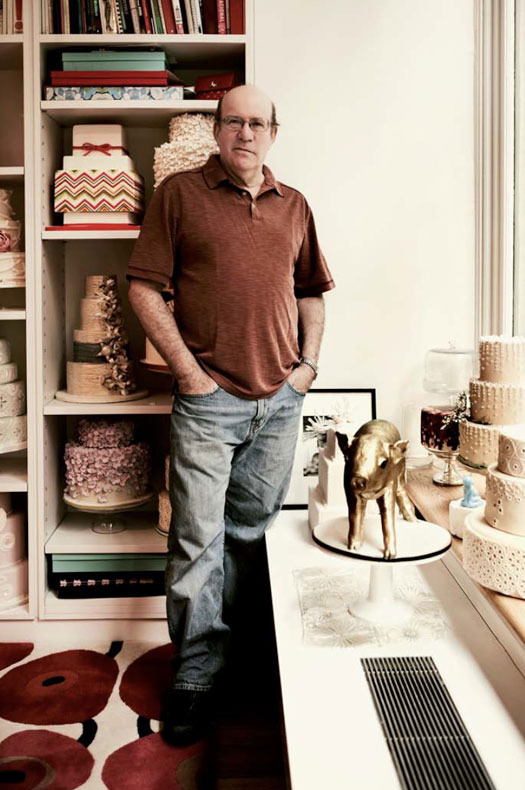

Photo by David Needleman

“Every once in awhile,” he continues, “you take some of the liquid that is forming at the bottom and you put it over the brisket while it's in the oven. And then an hour into the process, you add potatoes and carrots. You cut the potatoes in half and skin the carrots. I always put in a lot of potatoes because nothing is better later in the week than taking those potatoes, slicing them up, frying them in some butter and having them with your left over brisket. So about an hour and half into this process, you add a bottle of beer. I always use Heineken. There is no reason to use such good beer but it was what my mother used. It provides some liquid but the alcohol evaporates. You let the brisket cook from anywhere between two and a half to three hours. The longer it cooks, the better it is, because it's a tough cut of meat. So you have this wonderful brisket with burnt onions as well as potatoes and carrots. And a lot of leftovers if you live by yourself. It's a sort of simple, idiot-proof recipe.”

Food that develops with age is food that is prized by the Levinthal tribe. His mother used to make a sumptuous chocolate roll that always tasted better the day after it was baked. It remains the family dessert of choice to accompany all birthdays and anniversaries. “It's basically this chocolate sponge cake that you roll up with some whipped cream in the center of it. Then you put some powdered sugar on it. And after you slice it, you can then put some chocolate sauce on top of that.”

Levinthal’s face twitches. Discussing his family's culinary traditions has triggered a brisket-related memory. “The ideal way to serve brisket, which was the way my mother did it, was with potato pancakes. She made them very thin and extremely crisp. They were treasured by the four of us children ― it was very important that they be distributed equally.”

He leans forward slightly in his chair and adds dryly, “But because my mother used one of those old-fashioned potato scrapers. She used to say that the secret ingredient to her potato pancakes was her own blood.”

David Levinthal's Mother's Brisket

INGREDIENTS:

Three to three and half pounds of brisket with the fat trimmed

Two onions, sliced

One bottle of Heinz chili sauce

Three to four potatoes

Three carrots, peeled

One bottle of Heinekin beer

INSTRUCTIONS:

As described above.

David Levinthal's Mother's Chocolate Roll

INSTRUCTIONS:

1) Beat 6 egg yolks & 1/2 cup sugar well. Add 1/3 cup cake flour with 1/2 cup ground Ghirardelli

chocolate (sift first).

2) In a separate bowl, beat 6 egg whites with a little salt till peak. Beat in 1/2 cup sugar. Gradually fold the

two mixes together- light on top of heavy (egg whites on top of chocolate). Bake at 375 degrees for 15-

20 minutes. (Ready when cake separates from pan.) Bake in a greased jelly-roll pan lined with parchment.

3) As soon as the cake is done, put a dishtowel (you can dust it with powered sugar) over the cake and

flip it out. Peel off the parchment while hot. Roll up cake while hot and leave it to cool. Then fill it with 1

cup of whipped cream mixed with 1 T powered sugar and 1/2 t vanilla. Do not over-whip. Roll up the cake.

A version of this article originally appeared on Gourmet Live!