Abstract

At the Aspen Design Summit sponsored by AIGA and Winterhouse Institute November 11–14, 2009, the Mayo Clinic Rural Healthcare Project considered what a massive, local rural healthcare intervention might look like. The Project envisioned working across Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation (CFI) platforms to research, prototype and build a healthcare delivery concept to improve healthcare services in rural communities.

The team focused on a CFI project already underway in Austin, Minnesota, where the healthcare system is considered broken. After examining the concept of community network building and well-being, the design mandate became the creation of a community health association called “Austin.us.” The goal is to create a network that changed the focus of the community from the consumption of healthcare to the collective production of well-being. The association’s network would allow community well-being to be driven through individual connections and change the currency of healthcare from dollars to commitment.

Austin, A Typical Town

Austin is a town of about 24,000 located an hour and a half southeast of Rochester, Minnesota. It’s the home of Hormel’s Spam plant as well as Quality Pork Products (QPP), another large meat processing business. Otherwise, Austin resembles many rural communities in the Midwest and Great Plains — a small concentration of low-slung retail and light manufacturing buildings in the midst of a sparsely-populated agricultural hinterland. Austin Medical Center, a Mayo Clinic affiliate, serves the community’s medical needs.

Mayo CFI researchers discovered that, like most of rural America, Austin’s healthcare system is inadequate. Residents are less likely to have had a healthcare visit in the past year, less likely to get prenatal care, more likely to visit the emergency room, and more likely to have delayed medical care or the purchase of drugs due to cost. Residents report that the system of care is fragmented; many critical specialties and specialized aftercare are unavailable locally.

The health ecosystem is further complicated by stakeholders with divergent interests. Despite its small size, Austin contains a heterogeneous mix of groups with different levels of access to healthcare, including a sizable concentration of undocumented workers. Other stakeholders include employers such as Hormel and QPP, that function as self-insured payers. The community has a number of civic organizations and governmental bodies that have only a tenuous link with healthcare services.

Initially there was some skepticism on the Project team about what a design intervention could accomplish. This was balanced by the opportunities in the situation. Seventeen percent of Americans live in rural areas, a substantial target population. Furthermore, a successful intervention in Austin would provide measurable evidence of the efficacy of community-wide healthcare interventions, something not possible in urban settings.

Focus on the Patient

The fundamental problem in Austin was not the sparseness of the population but the lack of connections among the people who lived there. Currently, the healthcare community concentrates largely on the conversation between the physician and patient. But the Project team postulated if people could talk to a wider array of community residents, healthcare provision would be both more comprehensive and less expensive (since a physician’s time is one of the most expensive elements of the healthcare system).

The team also shifted its focus from acute healthcare to overall well-being. The way to have a sustained conversation about health is to focus on an individual’s ongoing efforts to improve his or her physical welfare. Healthcare and well-being are closely linked. For someone who had a health crisis, recovery is discovering how to regain a sense of well-being given a new set of constraints.

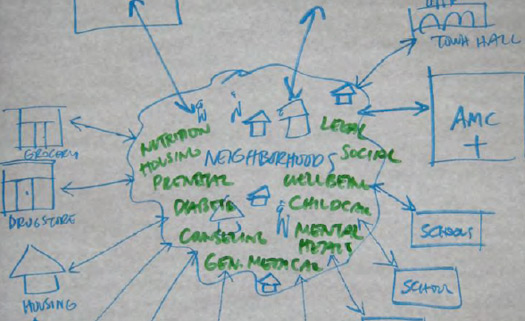

This focus on community network building and well-being led to the idea of creating a community health association called “Austin.us.” The association would create a network to refocus on the community’s collective well-being, driven by individual connections and with the goal of instilling commitments to improved individual well-being.

Defining Individual Roles in the Network

Rather than being centered on the physician, the group envisioned that healthcare responsibilities would be distributed across a wider network. Austin.us would serve to refer individuals both toward the primary care team as well as from the primary-care team to other nodes of a community network.

Physician involvement in the network was deemed a crucial component of the association’s success. Currently, a physician’s time is frequently taken up with routine monitoring or reassurance of patients. These tasks could properly be accomplished at less costly nodes of the network, allowing physicians to practice “at the peak of their license.” Patients conventionally desired direct physician contact. Therefore, a physician’s reliance on the network should be explicit. For example, a physician could “prescribe” conversations with community health workers and/or volunteers as part of a given course of treatment, legitimizing the role of the community network. The physician’s new slogan might be, “The doctor will connect you now.”

In addition, the network would depend on paid community health workers who would monitor chronic conditions and act as patient advocates with physicians or help a given individual connect to other nodes of the network. While such an individual should have healthcare training, the group thought it was equally important that community health workers would have project management skills.

Besides the paid portions of the network, the design team imagined a network heavily dependent on volunteers from the community. Roles could include volunteer promoters (generalists, such as a pastor in Austin who routinely helped parishioners monitor their blood pressure); volunteer promoters who are specialists (a grandmother, for example, who gives advice on parenting), or cancer survivors advising others on treatment; and supporters throughout the community.

Network Building

Several steps are involved in building a network; the first is mapping. There are health resources beyond the medical center in Austin, but they are fragmented and unconnected. If these invisible resources were made visible in a community-generated map, it would provide the initial connection to allow the network to emerge. A community-generated resource map could be posted to the internet and shared on Austin.us.

In addition, a number of dynamic web sites would provide entrée for community residents. A primary goal of these web sites would be to make content fun and engaging to encourage community participation. Possible web resources include: community characters (with videos and personal pages of residents); community calendaring system which aggregates community events and provides ability to publicize new health related events; community challenges, such as point system which rewards individuals for achieving health goals.

Physical connectors are also critical. Unlike virtual networks such as Facebook and MySpace, Austin.us should organize on the ground, providing opportunities for design interventions.

These include affinity badges and "walking” portals — LIVESTRONG-type bracelets to identify members of the association and for people who want to be more active — as well as T-shirts and badges that say, “Ask me, I am a well being.” A commercial portal would provide incentives for the community by offering special prices and deals for people in the association. Posters explaining the association would be seen at churches, coffee shops and recreation centers; tables would be staffed by volunteers to enlist new members or provide help. Pop-up exhibits would inform people in buses, and at street fairs and carnivals. A “Trojan Horse” health center with an inviting front-end would provide a place to just hang out as well as gain more substantive information. One possibility is "Shake and Bake” — a storefront that offers Dance, Dance Revolution and Wii-Fit type games, as well as cooking materials and instruction.

Funding Models

Most of the proposed interventions are not costly — at least compared to the cost of most medical procedures. Nonetheless, funding even modest interventions at a time when payers are putting pressure on providers to cut costs could reduce the space for experimentation and prototyping. The Project team identified two possible sources of funding: one is to offer self-insured employers a deal to front startup costs in return for the payment of a “bonus” if the model proved to reduce illness in the workforce and medical expenses for the company.

A second model works with third party insurers on the issue of a “medical home,” a place defined as the principal touch point of a patient within the healthcare system. Typically, this has been a primary care physician, but third-party providers have expressed interest in financing a transition to lower-cost community health workers as an individual’s medical home.

Next Steps and Action Plan

A group of design team members have agreed to meet to continue refining the financing model as well as prepare a pitch for potential benefactors. This work will happen in the first quarter 2010.

The suggestions made by the design team at Aspen have been forwarded to Mayo’s Center for Innovation. In December, Mayo will receive a formal research report from its team studying Austin, Minnesota. Then, a decision on what steps to take will be made. Various team members have agreed to help the Mayo group prototype the ideas presented above. Further, a Mayo CFI Advisory Board meeting is scheduled in Chicago for March, which includes many member who attended the Aspen Summit: CFI has committed that this project will be on the agenda.

While specific elements of the association will be determined by Mayo’s CFI and Austin, the network approach suggested by the team may have further application in other communities. A network-building toolkit around health care could be diffused to other locales and holds the promise of providing a way of inspiring grassroots efforts to greater wellness. The best way to reestablish the social contract on healthcare seems to be to focus on inter-individual connections rather than on some convocation of community interest groups.

Team Members

Moderator: Allan Chochinov, Editor, Core 77

Recorder: Jaan Elias, Director of Case Research, Yale School of Management

Maggie Breslin, Senior Designer/Researcher, SPARC Design Studio, Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation

Tim Brown, CEO, President, IDEO

Henry King, Global Account Manager, Doblin/Monitor

Carol McCall, Chief Innovation Officer, Tnezing Health, a subsidiary of Vanguard Health Systems

Margeigh Novotny, Vice President, Strategy and Experience, MOTO Development Group

Jay Parkinson, Pediatrician; Co-Founder, Hello Health

Barbara Spurrier, Administrative Director, Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation

Gong Szeto, CEO, yourowndemocracy.com

Helen Walters, Editor, Innovation and Design, BusinessWeek

Significant contributions to the writing of this report were made by Jaan Elias, Maggie Breslin and Allan Chochinov.

Documents

A PDF of the briefing book chapter on the Mayo Clinic Rural Healthcare Delivery Project is available here.

A PDF of a Powerpoint presentation by the Mayo Clinic Rural Healthcare Project team is available here: this is documentation of the process at Aspen, not indicative of final outcomes.

The original website for the Aspen Design Summit, as well as a list of all participants, is here.