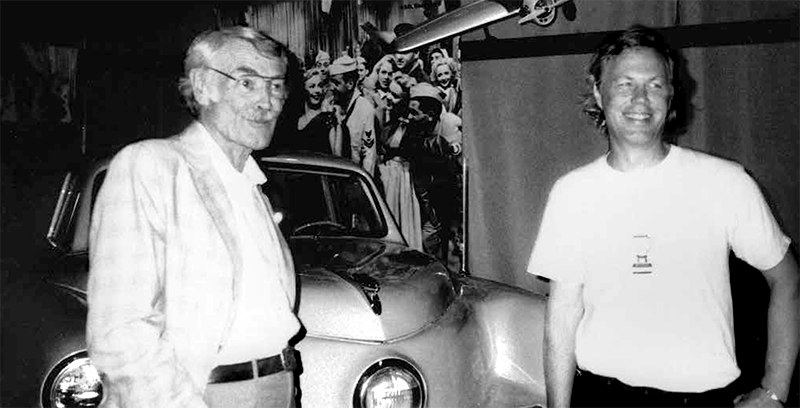

Along with a team from Lippincott, Read Viemeister, FIDSA (on the left) helped design the Tucker car (middle) and named his son, Tucker Viemeister, FIDSA (right) after it. This photo taken during a visit to a car museum during the 1991 IDSA conference in Boston.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2015 issue of the Industrial Designers Society of America Quarterly, INNOVATION, and has been condensed and reprinted here with permission of the author.

The beginning of industrial design set the stage for arguably the most influential era in design history: midcentury modernism. By “the beginning,” I’m not referring to the moment when the Renaissance emerged from the Dark Ages or the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. I’m referring to the time of unprecedented opportunity for designers like Norman Bel Geddes, Walter Dorwin Teague, and Raymond Loewy, who came from backgrounds in fashion and theater design. This was when, turbocharged by World War II, the explosion of new materials (like Plexiglas) and technology (like the TV) catalyzed innovation in industrial design. By bringing style to old and new machines, designers of this time created things that people wanted to use. They strove to beautify the ordinary, and their successes are now milestones in design, like Loewy’s housing for the Gestetner duplicating machine.

These early designers also believed that design led progress. They not only created desirable things—they also used them to promote the idea of societal advancement. Good design suggested a good life. And this led to good business. Loewy declared, “There is a frantic race to merchandise tinsel and trash under the guise of ‘modernism.’ I can claim to have made the daily life of the 20th Century more beautiful.” That made him a hero, and he was put on the cover of Time magazine. His work was considered groundbreaking.

This type of progressive design lasted until the 1960s, when the founding designers began retiring and hippie culture began reshaping the arts. Art and design became experimental, decorative, and counterculture. This new direction did not appeal to all designers, particularly those in accounting and engineering fields, or those with their own design sciences tailored to marketers and appraisers. These designers would intentionally refrain from the sensual and emotional, and instead grounded their work on human factors. Dieter Rams ranked aesthetics third in his ten commandments for good design, after utility and innovation. Likewise, design schools moved away from art schools. A common value for beauty quickly became lost in the general rush for progress, efficiency, comfort, and entertainment.

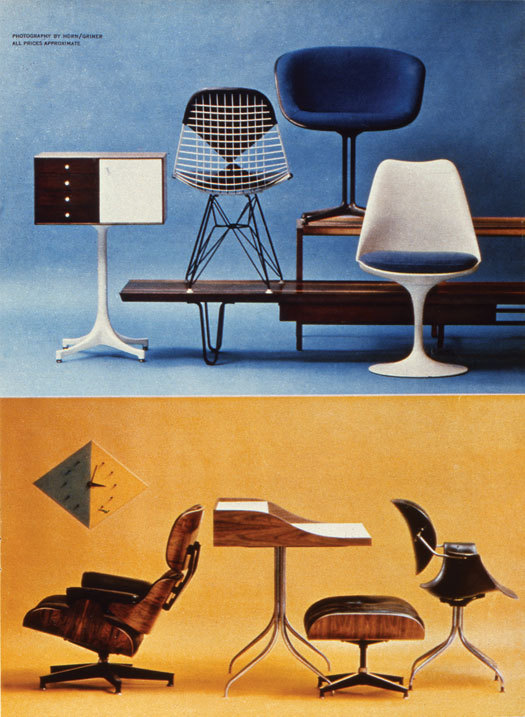

A page from a Playboy magazine article featuring Eames, Nelson and Saarinen furniture. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 2010

Why is midcentury modern design so lastingly beautiful? Perhaps it is partly because midcentury designers cared deeply about beauty as a standard in quality design. That kind of commitment was evident in the beautiful objects designed by Ray and Charles Eames, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Eliot Noyes, and Nelson. These designers were on a quest: to show how good design was good for everyone. Bertoia said, “The urge for good design is the same as the urge to go on living.”

But perhaps it is also because most midcentury designers took an interdisciplinary approach, striving to create products that encompassed utility and pleasure. To change culture, these designers organized design schools and research projects, put on competitions, created media outlets and global expos, and converted businesspeople and politicians to the cause of good design. Eliel Saarinen said, “Always design a thing by considering it in its next larger context—a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in a city plan.” So, perhaps midcentury design remains beautiful because the attitude to design was inclusive, and determinedly so.