Child Bollards, Leicester, England, 2009

These uncanny child bollards were placed outside Avenue Primary School in Leicester, England. Life-like in scale, their features are convincingly real to drivers moving at speed. Though they were designed to slow traffic, it is pedestrians who find them most disturbing. The frozen children staring straight ahead signal something is wrong. The dummies usurp the authority of adults, instructing them through fright. In making this a safe place for children, the city has inadvertently cast them in the role of zombies.

Author's Note: Where design projects possibilities, literature activates their potential. Brought together in Thinking Design through Literature, they form a new and wider tributary in the thought of things and places. That said, in this excerpt from the chapter on Beings, readers will note that the word ‘design’ is largely absent. That’s because few people, if any, refer to their possessions or homes or cities as ‘design.’ The reality is, we give our things names like table or apartment, and in this instance, golems and cyborgs. In naming these things, we bring design into life; but, perversely, they then become unremarkable. That is, until we meet them again in the context of literature. —Susan Yelavich

Stories of the supranatural would seem to be among those childish things it is long time we put away. But somehow we never do. Legions of superheroes with artificial appendages continue to invade our home screens. Monsters and aliens still want a piece of real estate on planet Earth — a suburban house or a skyscraper will do just fine. Crop circles and stone carvings are taken as signs that others have already been here. Clearly, all these Hollywood-manufactured scenarios are designed to exorcise our fears and hopes about the presence of other beings within the safe confines of fiction. But box office proceeds aside, these fabrications are driven by deeper investments in making more perfect companions. (And what could be more perfect than an idealized copy of oneself?)

The perennial urge to make our own doppelgangers would seem to be the ur-act of design — the creation of sentient beings by mortal beings. This is not simply a matter of mystical vitalism or escapist fantasy. The golems, puppets, cyborgs, and mutants of literature are manifestations of recognizable cultural neuroses, real psychological traumas, and the ever-fertile territory of visionary design. Their authors situate the outlandish in the familiar so that the outlandish can’t be dismissed as unthinkable. Their narratives fall along a spectrum from innocence to corruption. Virtually all of them are allegories of ethics and morality told through creatures — material surrogates — not abstractions. Some draw attention to the lively nature of things (e.g., dancing puppets), while others are enervating and lethal (e.g., rabid hybrids).

In an important sense, the literature of artificial proxies is as much about the reasons for designing as it is about the consequences of designing. These fictions — like design itself — combine a dicey pairing of hyper-rationalism and messianic romanticism, tilting toward the latter with its lore of the lone genius. In some cases, the design “products” in these stories are conscientious correctives to social or personal shortcomings. In others, they are avatars of unconstrained power, dangerous results of a single-minded determination to create another species at any cost. Designing with unfettered freedom in an exalted state of privilege is always risky, but never more so than when the goal is to assign sentience to mute materiality.

If we are to entertain these stories as seriously as they deserve to be (given that their fictions are gradually being realized), we must become temporary romantics. We need to admit the possibilities for the bizarre in otherwise ordinary situations — all the while acknowledging that the verifiable and the inexpressible qualities of places and objects do not observe strict borders, especially when viewed from a historical perspective.

Welcome to Seraing, Nik Baerten and Virginia Tassinari, with Yara Al Adib, Elisa Bertolotti, Pablo Calderón Salazar, Henriëtte Waal, 2015

Welcome to Seraing is a storytelling project that encouraged social innovation in the Trasenster neighborhood in Seraing, a Belgian city once famous for its steel industry, now facing severe socio-economic challenges. In collaboration with a local puppeteer, the design team worked to foster new forms of civil participation. Here, suspension of disbelief is not a retreat into fantasy but a state of mind and a safe space in which to speak out. The designers write that: “The anarchic character of the puppet theatre allowed [the puppeteer] the freedom to make the voice of Tchantchès (an outspoken working-class character) forthright and honest, and to intro-duce characters such as the Devil, representing the private owners of industries, and the White Fairy, representing the designers, who arrive with good intentions and a great deal of naiveté. Furthermore, an anonymous local hero was created as a surrogate for each and every inhabitant of Trasenster.”

Unruly Things, Rambunctious Marionettes

To understand how deeply the idea of willful things has permeated our consciousness, it is worth pointing out that the lore of animated matter isn’t just confined to the realms of fiction and poetry. History tells us that enlivened entities were not exceptional in antiquity. There are records of “soulless objects” being “sued, tried, convicted (but probably not acquitted), exiled, executed, and rehabilated.” In ancient Greece, a javelin could be tried and found guilty of murder “quite apart from the person who threw it.” Perhaps even stranger than the custom of attributing autonomous behavior to things is the fact that such legal decisions continue to inform the law today. Judgments like that of the javelin form the underpinnings of the legal fiction we know as forfeiture law. The practice of punishing things persists.

Unlike those who would dismiss it out of hand, legal scholar Paul Schiff Berman looks at how and why we continue to assign blame to objects. Little more than two decades ago, the U.S. Supreme Court stood by the State of Michigan’s decision to confiscate a jointly-owned car from its owners because it was the scene of a crime, despite the fact that one of the owners had no part in the incident. The automobile in question wasn’t forfeited because it had an “inherent vice” — the legal term for the fundamental instability of materials of the kind that accounts for rust. The car was taken from its owners because it was deemed to be what theologians call an “occasion of sin,” a person or thing that invites immoral acts. In this case, illicit sex. Whether the act of banishing an offending object hinges on animism (as in the case of the actively guilty javelin) or association (as with the passively guilty car), the intention is the same: to heal a rupture in the social order by removing the corrupted object from sight. The object is punished — removed from society — not the person or persons.

Virtually all such banishments occur after the commission of crimes; there’d be no point in exiling an innocent thing. But innocent doesn’t mean mute. The notion that things talk to each other and that they talk back to us, reflects their relational nature as well as the interdependence of people and things. We swear when something fails us; we say things like “my car has a faulty battery,” as though the battery were culpable. Such conflations of feelings and functions recognize that a capacity for action inheres in things — in their hinges and joints, their sensors and skins, even their data, which is arguably a form of speech. This is why multiple potentials — latent and obvious — can be identified in things well after they are designed. But what about before they are designed?

Unabomber Cabin, FBI Storage, Sacramento, CA, Richard Barnes, 1998

The Unabomber’s Cabin wasn’t removed from the community because anyone thought it was the embodiment of evil — even though it harbored a terrorist. Nevertheless, it was placed in secure FBI storage (an act rationalized as the protection of evidence) as though it carried a taint of evil in its wooden boards. The phenomenon of placing the banished on display is also repeated endlessly in museums. A perverse romanticism pervades the narratives of their isolation. Whether in a typical exhibition case or a mammoth hangar, they take on the aura of caged animals.

***

Pinocchio, written by Carlo Collodi in 1883, is such a case. Its famously naughty, eponymous protagonist makes his first appearance in an indeterminate state of nature — a rambunctious spirit trapped inside a raw piece of wood. He has a mind of his own but as yet no form, and more critically, no conscience. The design project is the union of this trinity: brain, body, and a moral compass. Indeed, much has been made of the Blue Fairy as the Madonna, Geppetto as Joseph the Carpenter, and Pinocchio as the Christ taking on human form. But this puppet is not the incarnation of divine power or any kind of rival to the Messiah. Pinocchio just wants to be a “real boy.” (In the newly united Italy of the time, “real” could be also taken as a metaphor for the process of making a nation out of formerly separate provinces.) Even his name tells us that this is a decidedly earthbound myth. Translated literally from Italian, pino means pine and occhio means eye.

Pinocchio’s journey of becoming starts when Geppetto sets out to carve the block of wood. The carpenter quickly discovers he’s not in control. When Geppetto fashions the nose, it keeps growing; the mouth, even before it was finished, starts laughing and mocking him. Geppetto is a designer who believes he can determine how raw materials will evolve despite all the evidence to the contrary right in front of him.

“Stop laughing!” said Geppetto, annoyed. But it was like talking to a wall. “I said stop laughing!” he yelled in a threatening tone.Taming the wild child would seem to be the project of the book — Pinocchio’s progress is constantly halted by temptations — but as the philosopher Benedetto Croce observed, Pinocchio is carved from the “wood of humanity itself.” The idea of designing with live matter — which is what Geppetto unwittingly is doing with his tools — raises another prospect: that we animate to exceed our limitations. (Deploying a familiar trope in the literature of beings, Collodi empowers Geppetto with the capacity to make a son, not out ofa woman’s womb but out of love for his wooden miscreant.) This kind of design ambition in extremis plays out in cautionary narratives that don’t always come with happy endings. Characters like Pinocchio — who after all his misadventures is amazed and delighted to be fully human — are greatly outnumbered by beings that materialize out of plans and accidents much less innocent than Geppetto’s.

The mouth stopped laughing but stuck its tongue all the way out.

Not wanting to damage his own handiwork, Geppetto pretended not to notice and kept on working.

Talos, Neri Oxman with W. Craig Carter (MIT) and Joe Hicklin (The Mathworks), produced and 3D printed by Stratasys, 2012

Like wearable golems, Neri Oxman’s prototypes augur an era in which myths become wearable and habitable. Her project Talos is one in a series entitled “Imaginary Beings: Mythologies of the Not Yet.” (In Greek mythology, Talos was the embodiment of armor.) Oxman’s wearable shield varies its thickness to accommodate for soft regions requiring more protection and for stiff regions covering bone perturbations. Talos bears no small resemblance to the superhero costumes that glorify the human physique. However, like all armor, it positions the body itself as a threat to life by virtue of its vulnerability.

Golems: Saviors, Monsters, Singular Surrogates

Where an excess of life force invigorates Collodi’s puppet, dread and fear mold creatures of crisis, like superheroes, figures whose powers compensate for our lack. In Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, caped crusaders emerge on American comic book pages, drawn out of their Jewish creators’ frustrated hopes for the rescue of family and friends stranded in Hitler’s Europe. In this quasi-fictive version of the birth of the comic book trade, we bridge the world of childlike toys and adult escape of the most literal sort. Written in 2012, the novel centers on two cousins, Sam Klayman and Josef Kavalier. Josef arrives in New York in 1939, an émigré from Europe. Sam gets him a job where he works at the Empire Novelties Incorporated Company and they begin working together to create their own superhero.

Spirited out of Nazi-controlled Prague in a magician’s wooden box, Josef’s near-miraculous escape is the set up for the cousins’ choice of hero and his roots in the myth of the golem. A creature of Jewish folklore, the golem is a giant typically fashioned out of clay or wood and brought to life, first by incantations and then by the hands which give it form. Sam explains to Josef that:

Every universe, our own included, begins in a conversation. Every golem in the history of the world, from Rabbi Hanina’s delectable goat to the river-clay Frankenstein of Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, was summoned into existence through language ... literally talked into life.Together they create “the Escapist, Master of Elusion,” a golem formed out of “black lines and the four-color dots of the lithographer,” who carries his power in a Golden Key: “He frees people, see.” Chabon’s golem lives in that liminal space between metaphor and material reality. For Josef, it was briefly incarnated as a wooden coffin made for rescue, his vehicle for a Houdini-inspired escape from Prague. Sam’s golem, the Escapist, is a figure of conscience but also a figure made of lines on a page that made them into artists. And like the golem, these lines exist in a liminal space between the image and the imagined.

Madonna Lamps from People and Saints of Four Races series. Konarska-Konarski, 2010

These Madonna Lamps are designed by Polish designers Beata Konarski and Pavel Konarska. Perhaps even more interesting than the lamp’s chromatic allusions to race is its merger of lamp and figure to produce the ineffable light of a halo. The convergence of secular and sacred would seem to be a fitting tribute to someone we are told was an ordinary girl graced with an “immaculate” conception. Made of concrete and light, the lamps, like O’Brien’s characters, conjure a state of being in-between that characterizes myths like Mary’s.

Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Golem” also portrays the creature in words. However, this one is conjured not to save others but out of a desire for self-ag- grandizement. Borges uses the structure and tempo of poetry to gesture toward the ritualized nature of a pseudo-divine creation. This is a step beyond the naïve, wishful thinking that Kavalier and Klayman brought to life with ink and paper.

With Borges, we move from the altruism that renders Chabon’s golems to the hubris that attempts to make a being, an attempt whose only purpose was wield the power of life without the intervention of God or a woman. (It is as though Pinocchio is written in reverse; instead of discovering life in a puppet, Borges’ rabbi tries to insinuate it into a dummy.) In this excerpt from “The Golem” not only do we get a more visceral understanding of matter conjured to life, but also an echo of the Biblical origin myth in which God fashions Adam out of clay and creates a flawed (albeit, human) being.

***

Apart from functioning as prophetic signs of warning, the golem and other paranormal figures are significant as objects — objects not outside the mind but within it— objects that form us. Such imaginings are as much a part of our psychological makeup as the things we played with, the environments we grew up in, and the persons we’ve encountered. We are as much the product of the stories we hear and tell as we are of our tangible surroundings. When we internalize such object-myths — like that of the incompletely human “thing” that Borges describes, they carry the potential for what psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas calls “a complex psychosomatic experience.” In other words, a state of mind that elicits the senses, and thus cannot be divorced from reality. This is why, I would argue, we cannot dismiss golems or other invented beings out of hand. These “evocative objects,” to use Bollas’s term, are designed and deployed with consequence, namely as projections of more powerful selves.

With Borges, we move from the altruism that renders Chabon’s golems to the hubris that attempts to make a being, an attempt whose only purpose was wield the power of life without the intervention of God or a woman. (It is as though Pinocchio is written in reverse; instead of discovering life in a puppet, Borges’ rabbi tries to insinuate it into a dummy.) In this excerpt from “The Golem” not only do we get a more visceral understanding of matter conjured to life, but also an echo of the Biblical origin myth in which God fashions Adam out of clay and creates a flawed (albeit, human) being.

Thirsty to know things only known to God,Failing to acquire the infinite knowledge and power of God, the rabbi produces a deeply fallible creature and suffers the consequences of seeking total control. (This is a risk that gods and designers take repeatedly.) Borges’s creature exists only to punish its maker’s hopes, living as it does trapped in a human chronology of “After, Before, Yesterday, Meanwhile, Now.” Not only is the golem denied access to the divine, it is also denied the possibility of being completely human. In that sense, Borges’s golem is also like Adam’s descendants, who were forced to live half-lives imprisoned in the confines of ghettos. In another sense, the poem is also recognizable as a portrait of failure: of the “potent sorcery” that “never took effect.” This is also the failure of design (or any kind of making) when it is approached as pure invention (flowing solely from the designer’s “sorcery”) instead of as the work and play of discovery. Nothing, and more to the point, no one, is sui generis.

Judah León shuffled letters endlessly,

trying them out in subtle combinations

till at last he uttered the Name that is the Key,

the Gate, the Echo, the Landlord, and the Mansion,

over a dummy which, with fingers wanting grace,

he fashioned, thinking to teach it the arcana

of Words and Letters and of Time and Space.

The simulacrum lifted its drowsy lids

and, much bewildered, took in color and shape

in a floating world of sounds. Following this,

it hesitantly took a timid step.

Little by little it found itself, like us,

caught in the reverberating weft

of After, Before, Yesterday, Meanwhile, Now,

You, Me, Those, the Others, Right and Left.

That cabbalist who played at being God

gave his spacey offspring the nickname Golem.

(In a learned passage of his volume,

these truths have been conveyed to us by Scholem.)

....

Perhaps the sacred name had been misspelled

or in its uttering been jumbled or too weak.

The potent sorcery never took effect:

man’s apprentice never learned to speak.

Its eyes, less human than doglike in their look,

and even less a dog’s than eyes of a thing,

would follow every move the rabbi made

about a confinement always gloomy and dim.

Something coarse and abnormal was in the Golem.

***

Apart from functioning as prophetic signs of warning, the golem and other paranormal figures are significant as objects — objects not outside the mind but within it— objects that form us. Such imaginings are as much a part of our psychological makeup as the things we played with, the environments we grew up in, and the persons we’ve encountered. We are as much the product of the stories we hear and tell as we are of our tangible surroundings. When we internalize such object-myths — like that of the incompletely human “thing” that Borges describes, they carry the potential for what psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas calls “a complex psychosomatic experience.” In other words, a state of mind that elicits the senses, and thus cannot be divorced from reality. This is why, I would argue, we cannot dismiss golems or other invented beings out of hand. These “evocative objects,” to use Bollas’s term, are designed and deployed with consequence, namely as projections of more powerful selves.

It is worth noting here that the particular psychosomatic experiences that nourished generations of golems have been the exclusive province of men who, it must be said at the risk of being obvious, cannot otherwise give birth. It is not just Jewish men who have felt compelled to project themselves into the world by creating living beings from scratch, as it were. The notion that a life can be engendered solely (and literally) from a male body has roots in ancient beliefs in the superiority of sperm over menstrual blood. This fiction (and no doubt others beyond our scope) laid the groundwork for the notion of monogenetic reproduc- tion that alchemists would find so compelling in the sixteenth century. One of the best known was the Swiss physician and occultist Paracelsus, who believed it was truly possible to create a “Man out[side] of the body of a Woman.” (It involved keeping sperm heated by horse dung.)

Putting such radical attempts to make women completely expend- able aside, we find history casts women in the role of mediums. (Even the “Immaculate Conception” entailed the intervention of the Holy Spirit.) Women are almost never independent progenitors. We had to wait until the last gasp of the twentieth century for a female golem to emerge from a woman, not from her womb but from her mind and a messy urban environment.

***

Cynthia Ozick’s 1997 novel The Puttermesser Papers is a story of revenge against centuries of myth mismanagement — mismanagement as viewed from a feminist perspective, which would argue against male privilege in the art of the golem. The story opens in an equally mismanaged New York City. The traditional rabbi’s role is given to Ruth Puttermesser. Fortyish, childless, and unmarried, Ruth is an attorney who works in the Department of Receipts and Disbursement, from which she is summarily demoted and fired when political patronage favors someone else. Humiliated by bureaucrats, she’s then dumped by her married lover Rappoport for reading Hebrew in bed. The next day Ruth wakes to find a naked adolescent girl — a golem unwittingly fertilized by Ruth herself with the flotsam and jetsam of her Manhattan apartment, specifically the soil from the broken crocks of her houseplants and a particularly hefty bundle of the Sunday Times. As always, in the beginning was the word: words and dirt.

Like her predecessors, Ruth’s golem Xanthippe exists to serve. Xanthippe takes her name from Socrates’ wife, and as a wife, her first duties are to cook and clean. But also, like Socrates’ wife, whose argumentative nature purportedly prepared him for his dealings with men, she is far more than a servant. She becomes the force behind Ruth’s rise to power. When Ruth decides to run for office, Xanthippe takes on the role of campaign manager and becomes Ruth’s first political appointee. Her trajectory from home to office allows her to realize Ruth’s civic-minded dreams and insure she succeeds in becoming Mayor Puttermesser. None of this is accidental because we’re told from the start that “the difficulty with Puttermesser is that she is loyal to certain environments.” She is especially dedicated to the difficult city she grew up in. So, when she discovers that a golem thrives on a vision of Paradise, Ruth immediately recognizes the Eden that she and Xanthippe will bring about:

There can be no “next generation” for a limited edition of one. Infertility is the tragic flaw of golems, robots, puppets, and other such creatures, seemingly regardless of their gender. Their progeny come through imitation, and one golem’s story begets another’s. It seems that each generation — driven by its own existential anxieties about the future — is impelled to revisit the same stories and transfer its fears onto, and into, surrogate forms. We labor under the delusion that we can control these objects of design (and their consequences) since we cannot dictate our own scripts. But the best we can do is make them in such a way as to not foreclose the future, itself, from possibility — either because they encourage fantasies of rescue (as with golems) or because they obscure the toll they take on the environment (as with products of design that contribute to global warming).

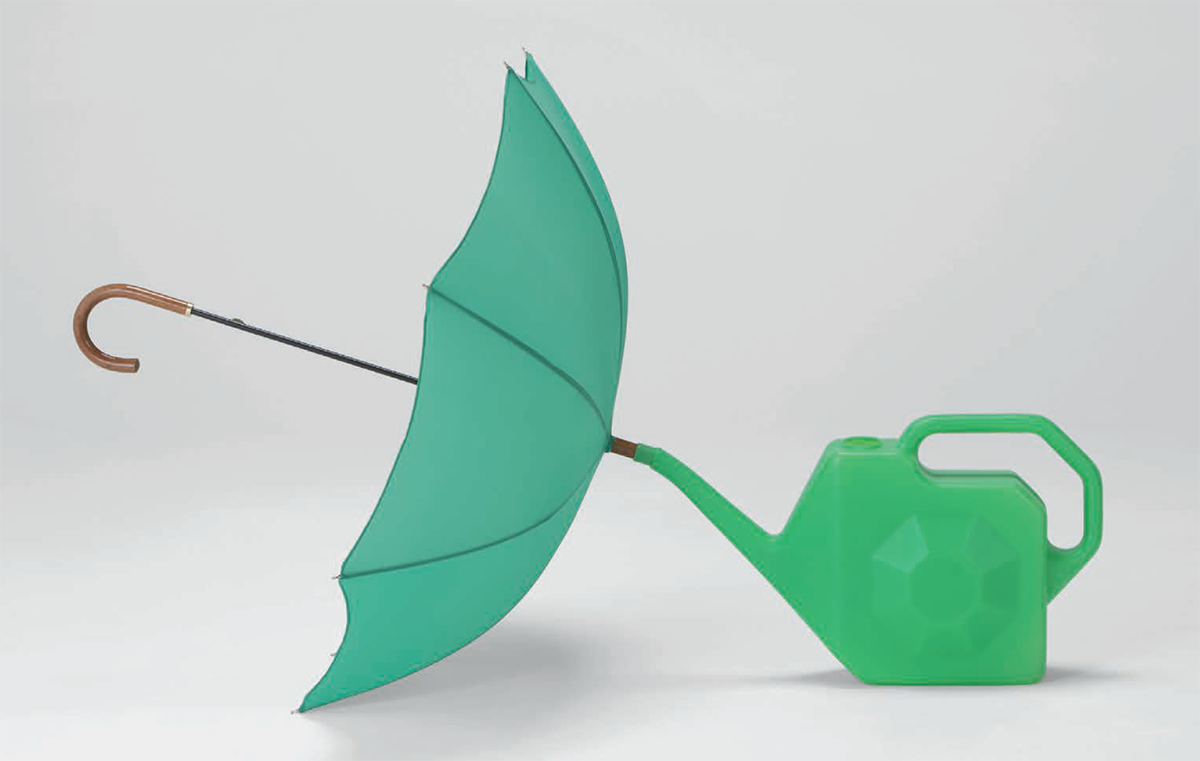

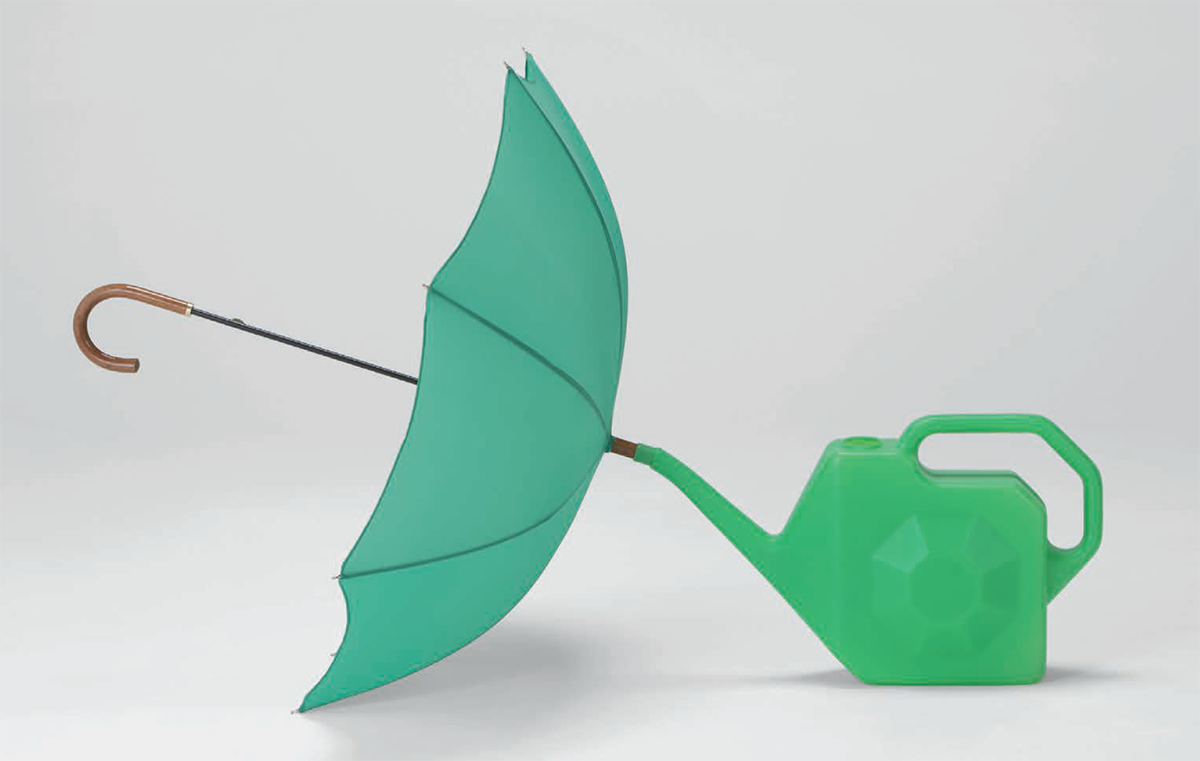

Umbrella + Watering Can, part of One + One collection, © 2012 Daniel Eatock

The umbrella-cum-watering can operates on the logic of the bicycle-characters in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman. Both rely on the absurd to demonstrate an uneasy mutual dependence. In the case of One + One, the rain we wish to avoid is essential for watering plants; in the case of the half-human bicycles, wheels and legs, handle bars and arms, are as essential for getting around as they are for getting in trouble with the law. The umbrella complements the workings of the watering can, and in The Third Policeman, the bicycle does the same for the body. To paraphrase design scholar Clive Dilnot, design is indispensable because we humans are “essentially failed animals.” Unable to shed or collect water with our hides, we make portable canopies and spouts. Here, Eatock’s objects are not linked with people but with each other, resulting in an uncanny new being, apart from us.

All the works in this chapter could be said to be manifestations of the desire to exceed our capacities for control. But where most revolve around a utopian desire for a better world in this life, Flann O’Brien (pen name of Brian O’Nolan) situates his quest for equilibrium in the next. The Third Policeman is set in the hereafter — a most bizarre hereafter at that. (There is some irony in the fact that the novel was published posthumously in 1967, after O’Brien’s own death in 1966.) Here, bodies aren’t resurrected intact. Instead they are recomposed. The molecules of objects and people get mixed up to the point where they’re no longer completely separate. At the time this truly was a fanciful idea, whereas today there is ample evidence that particles of microplastic have infiltrated our bodies by way of our food. O’Brien, however, is projecting a scenario that is far less granular; his is less a critique of science than of religion and bourgeois values. Accordingly, the hybrid beings in The Third Policeman are trapped in an afterlife that’s closer to limbo than a state of final rest. We are never explic- itly told that this is the case; even our protagonist doesn’t seem to know he’s dead. Rather, we (and he) experience this peculiar Irish purgatory in the vagaries of novel’s circular plot — a plot driven by bicycles.

The tale begins with an admission of murder by the accomplice to the crime. The narrator doesn’t so much confess as matter-of-factly state that he delivered the final blow to “old Mathers.” As it happens, the first (and fatal) blow came from one John Divney, who hit the man “with a special bicycle-pump which he manufactured himself out of a hollow iron bar.” (The pair of conspirators were after the man’s strong box.) From here on in, our narrator will never escape the ubiquitous bicycle and its accessories.

It is by bicycle that he returns to Mathers’ house, where Divney claims to have hidden their ill-gotten gains for their own safety. Of course, they aren’t there, but Mather (or his specter) is. After a conversation about policemen who give out gowns whose color indicates whether one’s life will be long or short, our man is persuaded that these prescient authorities — the guardian angels of bicycles — must be able to help him find the missing box and the thousands of negotiable securities inside it.

Arriving at the police barracks, he’s asked if he’s come to inquire about a bicycle. Incredulous that he hasn’t, officer Sergeant Pluck is faced with “a very difficult piece of puzzledom, a snorter.” (And my favorite, “a supreme pan- cake.”) Pluck insists that the only possible crimes in these parts have to do with bicycles, not watches like the one our narrator uses as a pretext for his queries. Indeed, if the watch is found, says Pluck, “I have a feeling there will be a bell and a pump on it.” As if to clarify his non sequitur and explain why a bicycle must be implicated, the Sergeant tells him of another missing item. It seems an elderly woman was reported lost by her son, who describes her as suffering from rusty rims and jerky brakes. She and others appear to have been “banjaxed from the principle of the Atomic Theory.” (It’s worth remembering that nuclear fission was responsible for the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and more to the point of The Third Policeman, that the resulting fragments of fission are not the same element as the original atom. O’Brien gives the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation a neat double twist here.)

No other theories of loss or existence apart from the “principle of Atomic Theory” could possibly matter. Everything and everyone, including the narrator’s made-up missing watch, is subject to the law of dancing particles “lively as twenty leprechauns doing a jig on top of a tombstone.” Though in Pluck’s domain, the jig is more of a square dance. When an action is repeated enough, particles change partners.

But the bicycle is only partly to blame. The real crime is exercising — exercising a measure of independence from the strict social norms of 1960s Ireland. But the bicycle isn’t altogether innocent either as it is also a source of temptation and sin. The bicycles in The Third Policeman are endowed with latent (and sometimes lascivious) capacities, ready and waiting to be activated.

This is precisely the double-edged nature of design and its capacity to delegate morality to the stuff of life — the kind of delegation we usually associate with air bags or smoke alarms that keep us safe, but rarely with ordinary things like the two-wheeled vehicle at the hub of this story. Nor do we pay much attention to the most basic ways that things act,not just for and with us. but also instead of us — ethically or not. As the sociologist Bruno Latour argues, things exert agency, albeit indirectly, all the time: “In addition to ‘determining’ and serving as a ‘backdrop for human action,’ things might authorize, allow, afford, encourage, permit, suggest, influence, block, render possible, forbid, and so on.” Thus, the products of design — and designing itself — can be thought of as temptations to act, in the sense that temptation involves a conscious choice to act one way or another. In Sergeant Pluck’s domain, bicycles activate a mobility that is measured in both molecules and miles with statistical precision, as if to counteract the freedom inherent in movement. Though as we have seen, things don’t generally submit to the law’s checks and balances — hence their history of banishment and forfeiture.

The loveliness of O’Brien’s choice of the bicycle is that it is a fulcrum for critiquing provincial prejudices at the same time exposing the risks of design- ing even the most modest of things and letting them loose in the world. Case in point, despite the fact that he rides one himself, Sergeant Pluck is suspicious of bicycles. He fears they carry a high quotient of humanity within them and that their capacity for movement extends well beyond the road.

The peculiar workings of justice become clearer in the story of MacDadd and Figgerson. A simmering feud between the two men takes a bad turn after MacDadd assaults Figgerson’s bicycle with a crowbar. Figgerson challenges MacDadd to a fight and loses — badly. Defeated, dead, and properly waked, Figgerson and his bicycle are buried — the latter in a bicycle-shaped coffin specially fitted out to accommodate its extremities, its handlebars and foot pedals.

To continue reading Thinking Design through Literature you can purchase it here.

Putting such radical attempts to make women completely expend- able aside, we find history casts women in the role of mediums. (Even the “Immaculate Conception” entailed the intervention of the Holy Spirit.) Women are almost never independent progenitors. We had to wait until the last gasp of the twentieth century for a female golem to emerge from a woman, not from her womb but from her mind and a messy urban environment.

***

Cynthia Ozick’s 1997 novel The Puttermesser Papers is a story of revenge against centuries of myth mismanagement — mismanagement as viewed from a feminist perspective, which would argue against male privilege in the art of the golem. The story opens in an equally mismanaged New York City. The traditional rabbi’s role is given to Ruth Puttermesser. Fortyish, childless, and unmarried, Ruth is an attorney who works in the Department of Receipts and Disbursement, from which she is summarily demoted and fired when political patronage favors someone else. Humiliated by bureaucrats, she’s then dumped by her married lover Rappoport for reading Hebrew in bed. The next day Ruth wakes to find a naked adolescent girl — a golem unwittingly fertilized by Ruth herself with the flotsam and jetsam of her Manhattan apartment, specifically the soil from the broken crocks of her houseplants and a particularly hefty bundle of the Sunday Times. As always, in the beginning was the word: words and dirt.

Like her predecessors, Ruth’s golem Xanthippe exists to serve. Xanthippe takes her name from Socrates’ wife, and as a wife, her first duties are to cook and clean. But also, like Socrates’ wife, whose argumentative nature purportedly prepared him for his dealings with men, she is far more than a servant. She becomes the force behind Ruth’s rise to power. When Ruth decides to run for office, Xanthippe takes on the role of campaign manager and becomes Ruth’s first political appointee. Her trajectory from home to office allows her to realize Ruth’s civic-minded dreams and insure she succeeds in becoming Mayor Puttermesser. None of this is accidental because we’re told from the start that “the difficulty with Puttermesser is that she is loyal to certain environments.” She is especially dedicated to the difficult city she grew up in. So, when she discovers that a golem thrives on a vision of Paradise, Ruth immediately recognizes the Eden that she and Xanthippe will bring about:

A city washed pure. New York city (perhaps) of seraphim. Wings had passed over her eyes. Her arms around Rappoport’s heavy Times, Puttermesser held to her breast heartlessness, disorder, the desolation of sadness, ten thousand knives, hatred painted in subways, explosions of handguns, bombs in the cathedrals of transportation and industry ... the decline of the Civil Service, maggots in high management. Rappoport’s Times, repository of dread freight! All the same, carrying Rappoport’s Times back to bed, Puttermesser had seen Paradise.Under Mayor Puttermesser, crime goes down and the city becomes a paragon of Vitruvian virtues: firmness, comfort, delight. Subways and their tunnels sparkle; sanitation carts are heralded by flutes and clarinets. Vandals form dance clubs, children jump rope in the streets unharmed, office workers flock to libraries to study different languages. Puttermesser’s dream of a civil society, backed by her golem’s tireless energy, transforms the city into a latter-day Eden. Its “streets are altered into garden rows .... There are ... a hundred urban gardening academies. There is unemployment among correction offi- cers; numbers of them take gardening jobs.” All goes according to her “radiant PLAN” for the redemption of New York — a utopia by another name, and a wink to architect Le Corbusier’s ideal of the modern city, the Ville Radieuse, a.k.a. the Radiant City. Everything thrives. “Nothing is broken, nothing is despoiled. No harm comes to anything or anyone.” That is, up and until Xanthippe discovers sex. Eros crushes justice, putting an end to Mayor Puttermesser’s stint in office. Her ideals foreclosed, the topos of her utopia loses its blooms and starts to brown, all because Xanthippe is infertile.

New York washed, reformed, restored.

There can be no “next generation” for a limited edition of one. Infertility is the tragic flaw of golems, robots, puppets, and other such creatures, seemingly regardless of their gender. Their progeny come through imitation, and one golem’s story begets another’s. It seems that each generation — driven by its own existential anxieties about the future — is impelled to revisit the same stories and transfer its fears onto, and into, surrogate forms. We labor under the delusion that we can control these objects of design (and their consequences) since we cannot dictate our own scripts. But the best we can do is make them in such a way as to not foreclose the future, itself, from possibility — either because they encourage fantasies of rescue (as with golems) or because they obscure the toll they take on the environment (as with products of design that contribute to global warming).

Umbrella + Watering Can, part of One + One collection, © 2012 Daniel Eatock

The umbrella-cum-watering can operates on the logic of the bicycle-characters in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman. Both rely on the absurd to demonstrate an uneasy mutual dependence. In the case of One + One, the rain we wish to avoid is essential for watering plants; in the case of the half-human bicycles, wheels and legs, handle bars and arms, are as essential for getting around as they are for getting in trouble with the law. The umbrella complements the workings of the watering can, and in The Third Policeman, the bicycle does the same for the body. To paraphrase design scholar Clive Dilnot, design is indispensable because we humans are “essentially failed animals.” Unable to shed or collect water with our hides, we make portable canopies and spouts. Here, Eatock’s objects are not linked with people but with each other, resulting in an uncanny new being, apart from us.

All the works in this chapter could be said to be manifestations of the desire to exceed our capacities for control. But where most revolve around a utopian desire for a better world in this life, Flann O’Brien (pen name of Brian O’Nolan) situates his quest for equilibrium in the next. The Third Policeman is set in the hereafter — a most bizarre hereafter at that. (There is some irony in the fact that the novel was published posthumously in 1967, after O’Brien’s own death in 1966.) Here, bodies aren’t resurrected intact. Instead they are recomposed. The molecules of objects and people get mixed up to the point where they’re no longer completely separate. At the time this truly was a fanciful idea, whereas today there is ample evidence that particles of microplastic have infiltrated our bodies by way of our food. O’Brien, however, is projecting a scenario that is far less granular; his is less a critique of science than of religion and bourgeois values. Accordingly, the hybrid beings in The Third Policeman are trapped in an afterlife that’s closer to limbo than a state of final rest. We are never explic- itly told that this is the case; even our protagonist doesn’t seem to know he’s dead. Rather, we (and he) experience this peculiar Irish purgatory in the vagaries of novel’s circular plot — a plot driven by bicycles.

The tale begins with an admission of murder by the accomplice to the crime. The narrator doesn’t so much confess as matter-of-factly state that he delivered the final blow to “old Mathers.” As it happens, the first (and fatal) blow came from one John Divney, who hit the man “with a special bicycle-pump which he manufactured himself out of a hollow iron bar.” (The pair of conspirators were after the man’s strong box.) From here on in, our narrator will never escape the ubiquitous bicycle and its accessories.

It is by bicycle that he returns to Mathers’ house, where Divney claims to have hidden their ill-gotten gains for their own safety. Of course, they aren’t there, but Mather (or his specter) is. After a conversation about policemen who give out gowns whose color indicates whether one’s life will be long or short, our man is persuaded that these prescient authorities — the guardian angels of bicycles — must be able to help him find the missing box and the thousands of negotiable securities inside it.

Arriving at the police barracks, he’s asked if he’s come to inquire about a bicycle. Incredulous that he hasn’t, officer Sergeant Pluck is faced with “a very difficult piece of puzzledom, a snorter.” (And my favorite, “a supreme pan- cake.”) Pluck insists that the only possible crimes in these parts have to do with bicycles, not watches like the one our narrator uses as a pretext for his queries. Indeed, if the watch is found, says Pluck, “I have a feeling there will be a bell and a pump on it.” As if to clarify his non sequitur and explain why a bicycle must be implicated, the Sergeant tells him of another missing item. It seems an elderly woman was reported lost by her son, who describes her as suffering from rusty rims and jerky brakes. She and others appear to have been “banjaxed from the principle of the Atomic Theory.” (It’s worth remembering that nuclear fission was responsible for the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and more to the point of The Third Policeman, that the resulting fragments of fission are not the same element as the original atom. O’Brien gives the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation a neat double twist here.)

No other theories of loss or existence apart from the “principle of Atomic Theory” could possibly matter. Everything and everyone, including the narrator’s made-up missing watch, is subject to the law of dancing particles “lively as twenty leprechauns doing a jig on top of a tombstone.” Though in Pluck’s domain, the jig is more of a square dance. When an action is repeated enough, particles change partners.

The gross and net result of it is that people who spent most of their natural lives riding iron bicycles over the rocky roadsteads of this parish get their personalities mixed up with the personalities of their bicycle as a result of the interchanging of atoms of each of them and you would be surprised at the number of people in these parts who nearly are half people and half bicycles.The problem is that these centaurs of the mechanical age can become unbalanced: Pluck’s parishioners find themselves in all kinds of trouble. The postman has cycled himself into such a state that if he walks too slowly he collapses. A new “lady teacher” and a local man named Michael Gilhaney raise eyebrows when they go out with each other’s bicycles. Pluck worries that if things go too far bicycles will want the vote and “get seats on the County Council.”

But the bicycle is only partly to blame. The real crime is exercising — exercising a measure of independence from the strict social norms of 1960s Ireland. But the bicycle isn’t altogether innocent either as it is also a source of temptation and sin. The bicycles in The Third Policeman are endowed with latent (and sometimes lascivious) capacities, ready and waiting to be activated.

This is precisely the double-edged nature of design and its capacity to delegate morality to the stuff of life — the kind of delegation we usually associate with air bags or smoke alarms that keep us safe, but rarely with ordinary things like the two-wheeled vehicle at the hub of this story. Nor do we pay much attention to the most basic ways that things act,not just for and with us. but also instead of us — ethically or not. As the sociologist Bruno Latour argues, things exert agency, albeit indirectly, all the time: “In addition to ‘determining’ and serving as a ‘backdrop for human action,’ things might authorize, allow, afford, encourage, permit, suggest, influence, block, render possible, forbid, and so on.” Thus, the products of design — and designing itself — can be thought of as temptations to act, in the sense that temptation involves a conscious choice to act one way or another. In Sergeant Pluck’s domain, bicycles activate a mobility that is measured in both molecules and miles with statistical precision, as if to counteract the freedom inherent in movement. Though as we have seen, things don’t generally submit to the law’s checks and balances — hence their history of banishment and forfeiture.

The loveliness of O’Brien’s choice of the bicycle is that it is a fulcrum for critiquing provincial prejudices at the same time exposing the risks of design- ing even the most modest of things and letting them loose in the world. Case in point, despite the fact that he rides one himself, Sergeant Pluck is suspicious of bicycles. He fears they carry a high quotient of humanity within them and that their capacity for movement extends well beyond the road.

“You never see them moving by themselves but you meet them in the least accountable places unexpectedly. Did you never see a bicycle leaning against the dresser of a warm kitchen when it’s pouring outside? ... Near enough to the family to hear the conversation? Not a thousand miles from where they keep the eatibles?”Here, things, not people, are to blame. In this sense, the bicycle is a direct descendant of the criminal javelin prosecuted in ancient Greece, and a precursor of the sexualized American car, exiled in 1997. Although, in the context of O’Brien’s Catholic Ireland, it might be more apt to think in terms of original sin, the stamp of guilt everyone is believed to be born with. Here the sin of pride is transferred to everything we create — most especially bicycles. Yet, because sin is invisible, people (and their bikes) don’t look any different. As the Sergeant patiently explains, you can’t expect a man “to grow handlebars out of his neck.” He takes it for granted that the potential for sin infuses everyone and everything. However, new kinds of punishment are needed to fit the crimes of the parish’s doubly complicated citizens.

“You do not mean to say that these bicycles eat food?”

“They were never seen doing it, nobody caught them with a mouthful of steak. All I know is that food disappears.”

The peculiar workings of justice become clearer in the story of MacDadd and Figgerson. A simmering feud between the two men takes a bad turn after MacDadd assaults Figgerson’s bicycle with a crowbar. Figgerson challenges MacDadd to a fight and loses — badly. Defeated, dead, and properly waked, Figgerson and his bicycle are buried — the latter in a bicycle-shaped coffin specially fitted out to accommodate its extremities, its handlebars and foot pedals.

Meanwhile, the search for the killer MacDadd goes on.Appointed judge and jury, Sergeant Pluck duly condemns the bicycle to be hanged, entering a nolle prosequi for “the other defendant.” Surrogates are not projections of the ego here; they are sacrificial lambs. Indeed, our narrator is never punished for his alleged crime but nor is he free. Without a full confession of guilt, he’s left in purgatory, forever to be plagued by the question: “Is it about a bicycle?” The answer to the rhetorical question must be “yes,” because blaming things lets everyone off the hook.

We could not find MacDadd for a long time or make sure where the most of him was. We had to arrest his bicycle as well as himself and we watched the two of them under secret observation for a week to see where the majority of MacDadd was and whether the bicycle was mostly in MacDadd’s trousers pan passu if you understand my meaning.

To continue reading Thinking Design through Literature you can purchase it here.