© Bomboozled / Pointed Leaf Press

In George Orwell’s 1984, citizens of the totalitarian state of Oceania were required to accomplish the impossible task of holding two contradictory ideas in their minds and accepting both of them:

War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.

Orwell called this “Doublethink.”

Similarly, Americans during the early years of the Cold War between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. — the 1950s and early 1960s — were expected to be able to reconcile these two diametrically opposed thoughts:

A nuclear war can destroy all life on earth.

You will survive if you build a family fallout shelter.

The family fallout shelter’s ostensible purpose — to ensure survival during and after a nuclear attack — was impossible to achieve. That wasn’t why it was created. It was part of the propaganda campaign to convince the American people that they could survive a nuclear war.

Tens of thousands of Americans — maybe even hundreds of thousands — actually did build shelters, and millions considered doing so. Why? How could so many people believe that hiding in an underground concrete cube would save their lives during a nuclear attack? And then, if they somehow did survive, why did they believe they could function in a post-apocalyptic world with fires raging, cities destroyed, and a landscape littered with the dead and injured?

People built shelters because it was a desperate grab for empowerment in the face of the unthinkable. Doing something felt better than doing nothing.

© Bomboozled / Pointed Leaf Press

The roots of the family fallout shelter can be traced back to 1952, when the U.S. created a new bomb — the hydrogen, or thermonuclear, bomb — that was 1,000 times as powerful as the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

The world witnessed the astounding power of this new weapon on March 1, 1954, when it was exploded above the Marshall Islands in the Pacific. It threw several million tons of radioactive fallout into the atmosphere, fallout which can drift in unpredictable directions for thousands of miles over a period of years.

No longer was a nuclear bomb’s killing power limited to the place where it was detonated. Now everyone, everywhere was a potential victim of radioactive fallout.

The following year, the U.S.S.R. exploded its first hydrogen bomb. Fear of fallout gripped the nation. The government acknowledged that a bomb shelter would be useless against a direct hit by the H-bomb, which would destroy a bomb shelter as easily as the wolf blew down the house of straw in the fairy tale, The Three Little Pigs. However, it said, you can protect yourself against fallout. During a nuclear attack, go into your fallout shelter and stay there for two weeks, until the radiation in the atmosphere has dropped to a safe level.

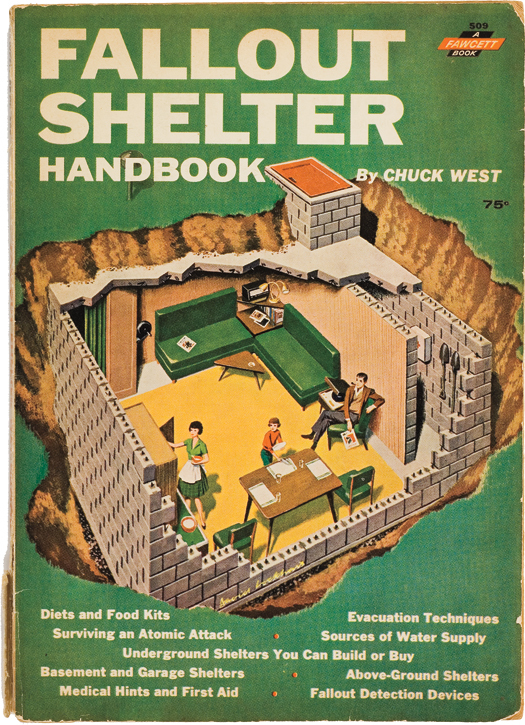

In 1959, the government published and distributed millions of copies of a 32-page booklet called The Family Fallout Shelter. It included step-by-step instructions for building the Concrete Block Shelter, a cube constructed of concrete block and mortar.

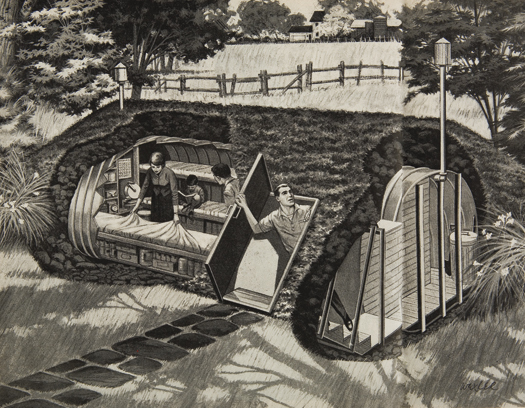

The Concrete Block Shelter could be installed in the basement. But for optimum protection against radiation, it should be buried in the backyard and covered with three feet of earth. Entry was to be through a ground-level hatch door. Drawings, photographs, and both miniature and full-size models of this shelter were disseminated in brochures, posters, television shows, Civil Defense films, public exhibitions, lectures, architectural journals, print advertisements, and large-circulation magazines. It became the iconic family fallout shelter.

Millions of Americans saw photographs in Life of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a messianic proponent of fallout shelters, sitting in a mockup of the Concrete Block Shelter in a New York City bank in 1960. Rockefeller installed shelters in his homes in Pocantico, New York, Washington, DC, and in the Governor’s mansion in Albany, New York. He even tried, unsuccessfully, to pass a law that would have required every New York State resident to have a family fallout shelter.

© Bomboozled / Pointed Leaf Press

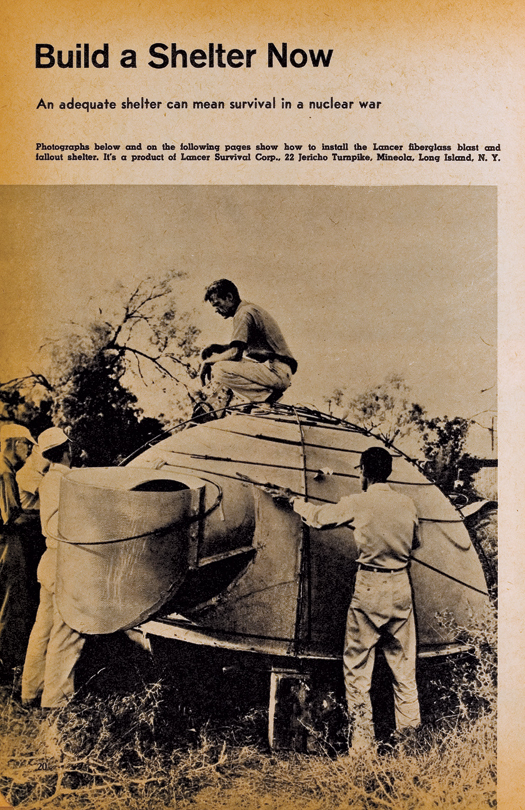

Sensing opportunity in the shelter market, materials makers leapt onto the bandwagon. The National Lumber Manufacturers Association published a booklet called Family Fallout Shelters of Wood, which included plans for a buried cubic room that required 2300 linear feet of lumber. In Steel Shelters for Fallout Protection, the American Iron and Steel Institute promoted the flexibility of a steel shelter. Because it is constructed of panels that are bolted or screwed together, “a shelter of steel does not saddle you with a permanent, hard-to-move ‘monument’ in your basement or yard when the current emergency is over.” For people who didn’t want to go the do-it-yourself route, there was a dizzying array of prefabricated shelters.

But whether built or prefabricated, shelters didn’t come cheap. The Concrete Block Shelter, for example, could cost more than $10,000 in today’s currency. But cost be damned! Building a shelter isn’t throwing money away; it is a prudent and patriotic step that every American must take to ensure his and his family’s survival. As the Civil Defense publication Individual and Family Preparedness declared, “Protection of our people is not new in the United States. When a free America was being built by our forebears, every log cabin and every dwelling had a dual purpose — namely, a home and a fortress.”

© Bomboozled / Pointed Leaf Press

Shelter mania peaked starting with the Berlin Crisis in 1961 and ended after the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the world came as close to nuclear war as it ever had, before or since. Once that crisis was safely resolved, Americans lost their interest in family fallout shelters. Polls showed that Americans rejected shelters because they had no faith that a shelter would protect them. Many people adopted a fatalistic attitude. As one poll respondent succinctly said, "Why should we do anything? If that bomb is dropped, we'll all be blown to bits anyway."

So, the Kennedy administration quietly abandoned its endorsement of the family fallout shelter. It shifted its attention to its National Fallout Survey, a program of identifying potential shelter space in existing buildings and marking these spaces with the now-iconic "Fallout Shelter" sign — three yellow triangles set inside a black circle on a yellow background. Now, fifty years later, these signs remain, rusted and faded legacies of the Cold War.

This piece is adapted from Bomboozled: How the U. S. Government Misled Itself and Its People into Believing They Could Survive a Nuclear Attack by Susan Roy (Pointed Leaf Press, June 2011).

So, the Kennedy administration quietly abandoned its endorsement of the family fallout shelter. It shifted its attention to its National Fallout Survey, a program of identifying potential shelter space in existing buildings and marking these spaces with the now-iconic "Fallout Shelter" sign — three yellow triangles set inside a black circle on a yellow background. Now, fifty years later, these signs remain, rusted and faded legacies of the Cold War.

This piece is adapted from Bomboozled: How the U. S. Government Misled Itself and Its People into Believing They Could Survive a Nuclear Attack by Susan Roy (Pointed Leaf Press, June 2011).