The human instinct for self-preservation manifests in interesting ways, especially when extended to insure the welfare of our progeny. Adults are constantly devising systems of rules to protect the youth of today so they will become the leaders of tomorrow. Fittingly, there is a curious— and long-lived—sub-genre of children’s literature specifically intended to counsel young’uns on the dangers of the world. If I had to coin a name for these kinds of book, I would probably choose “Books of Accidents,” borrowing the phrase from a group of related texts popular in the early part of the nineteenth century. Born out of a much broader category of books for juveniles—texts concerned with the salvation of young souls—these books of accidents addressed a very real and rapidly growing menace in the early modern period: the dangers of urban spaces. The rise of urban centers in the United States in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—concomitant with improvements in health care—meant that early childhood deaths from disease slowly began to be supplanted by deaths from more immediate and gruesome means: horse cart accidents and falls from windows.

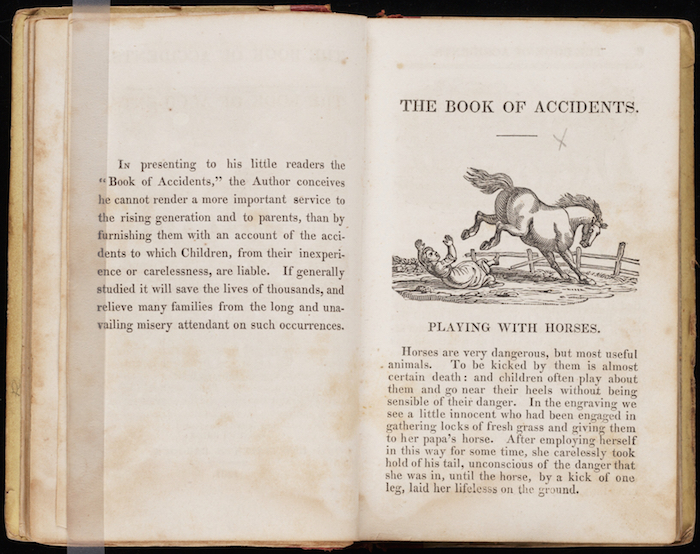

The Book of Accidents, published in New Haven, Connecticut, by S. Babcock in 1831 is a prime example of the genre. The intent of this book is stated in an introductory note: “In presenting to his little readers the ‘Book of Accidents,’ the Author conceived he cannot render a more important service to the rising generation and to parents, than by furnishing them with an account of the accidents to which Children, from their inexperience or carelessness, are liable.”

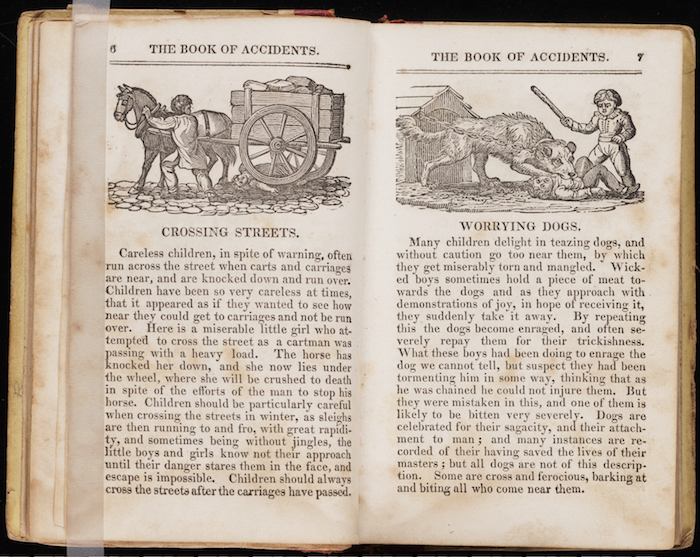

The inventory of accidents include: Playing with horses; crossing streets; worrying dogs; playing with knives; playing with fire-arms; climbing on chairs; and troubling the cook (“This little girl is seen rushing forward to tell some idle tale, perhaps, to the cook,” who proceeds to scald her by accidentally tipping a large pot of boiling water).

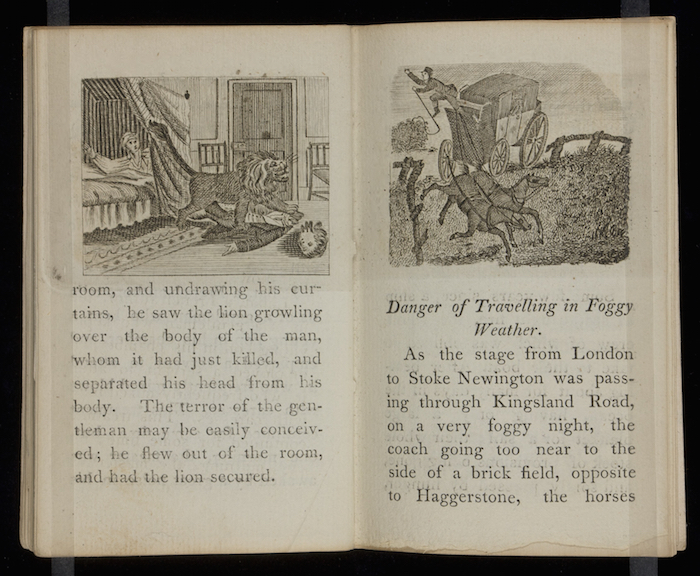

In the Third Chapter of Accidents, published earlier, in 1807 (seemingly out of sequence, but bibliographic order in children’s literature is, if anything, elusive), there are accounts of even more horrible events, such as may happen while “Travelling in Foggy Weather.” The tale that is most interesting is of The Young Lamp-Lighter who leaves his burner against a pole while going to get a beer, leaving his burner to be found by a pair of young boys who climb his ladder and become “giddy,” fall and are then scalded by hot oil.

A later publication, The Beacon; or Warnings to Thoughtless Boys, published in New York between 1856 and 1857, starts with the tale of John Stevens, a “very reckless boy,” who was prone to trouble and who ends up being crushed to death by a horse cart. The most bizarre tale in that collection is “The Mask,” transcribed here in its entirety:

Here is a mask. It is employed to conceal the face. It is a pretty thing for amusement, when it is properly used. A heedless boy once put on an ugly mask to amuse himself by alarming some very small boys and girls, and one of them was so terrified that she died the next day.

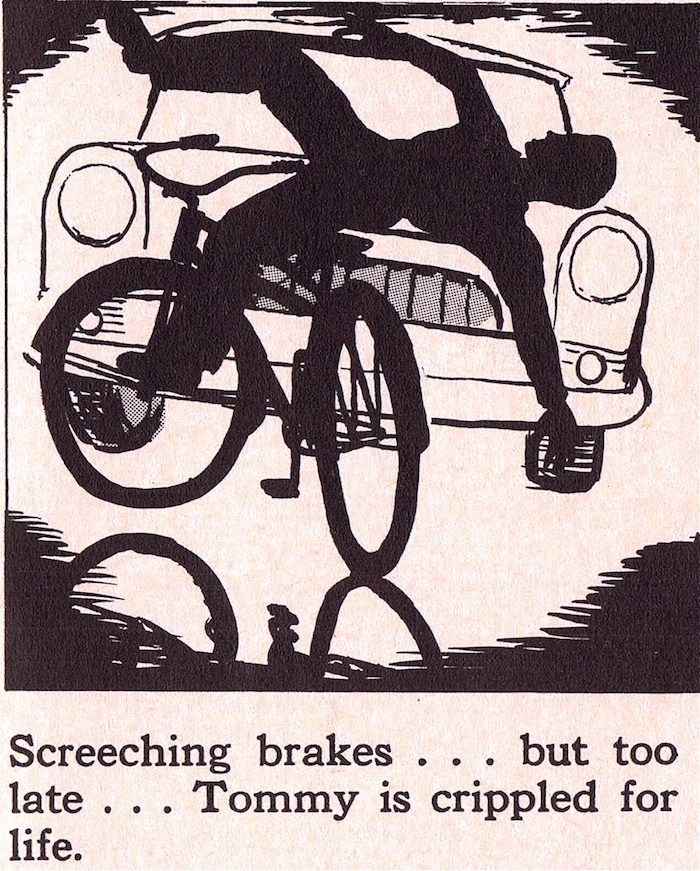

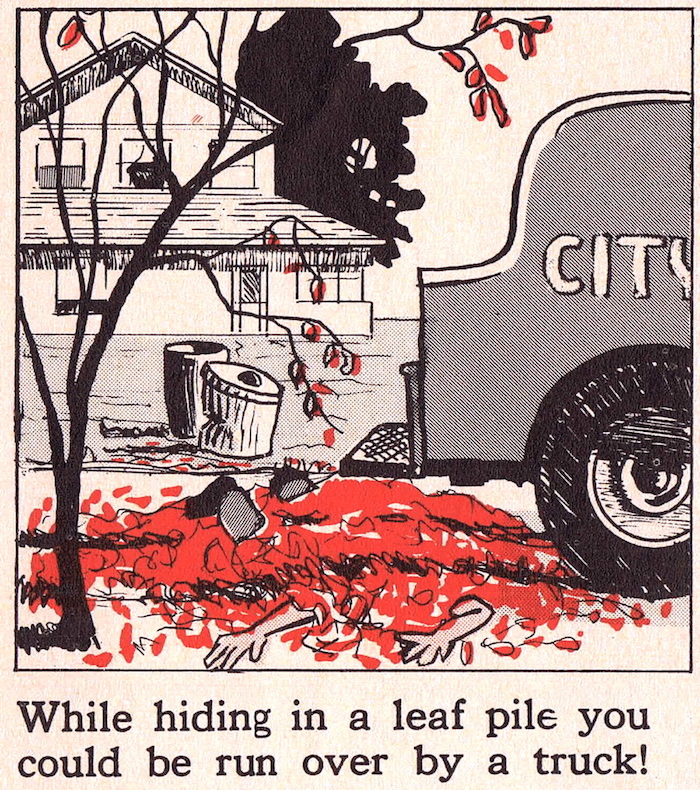

If any living readers are familiar with the genre of books of accidents, it may be through having read Edward Gorey’s dramatic appropriation The Gashlycrumb Tinies. But this stripe of book prevailed in the twentieth century in the form of pamphlets intended to instruct youngsters on bicycle and traffic safety. Some readers might remember booklets like “Bicycling is Great Fun …” published by the AAA or the placid “Bicycling Safety” from the Schwinn dealer, but the most frantic example of the mid-century safety booklet may well be “It’s Great to Be Alive.” This extremely rare item was discovered by Gene Gable, a designer and technology consultant who wrote about the booklet in a column for CreativePro.com. Some select quotes from the booklet: “Screeching brakes … but too late … Tommy is crippled for life” and “While hiding in a leaf pile you could be run over by a truck!”

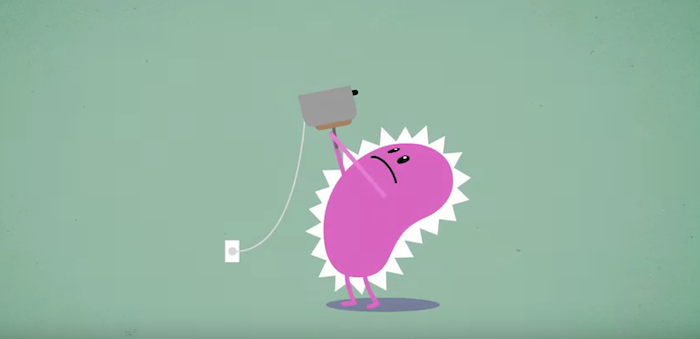

A twenty-first-century iteration of the child safety theme is “Dumb Ways to Die,” a rail safety campaign video from Melbourne, Australia, that became so popular, it was turned into an equally popular smart phone game. The original video, aligned with a snappy pop number, showing a cast of fruit-shaped, colorful creatures expiring in, well, dumb ways—including several that are train-related—has been viewed over 115 million times on YouTube. At the related online store, one can buy plush dolls and bag clips—the meme having turned from cautionary to cuddly, a complete semiotic U-turn.

But even with the earliest versions of these books of accidents, there was the likelihood that children would not read them for their intended message. Though we adults always want our children to heed the warnings presented in our cautionary books and videos, it may be more likely that they share them with each other by asking: “Do you want to see a dead body?”