Graphic design has a considerable appetite for talking about itself. Constant book releases, dedicated magazines and an over-saturated digital world creates a cacophony through which it is difficult to define that which is of genuine worth to the discourse.

Into this crowded environment arrives Branding Terror, a title that is rendered in gold foil stamping on black faux-leather hardback, a visual statement that suggests this book sees itself as an important tome. And perhaps it is? The authors, Arthur Beifuss (a journalist and former UN counter-terrorism analyst) and Francesco Trivini Bellini, a creative director with a portfolio of big accounts including Gucci and Prada) certainly have the credentials to pose a little-asked question: how great a part does graphic image-making play in the effectiveness of the most active international terrorist groups?

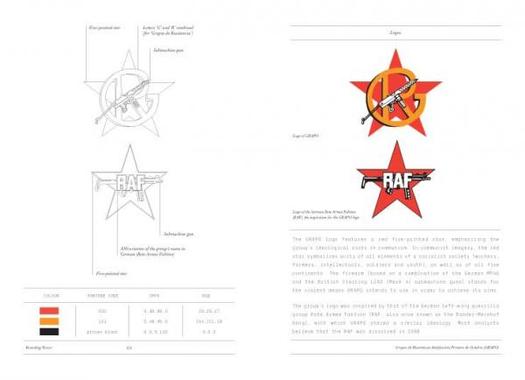

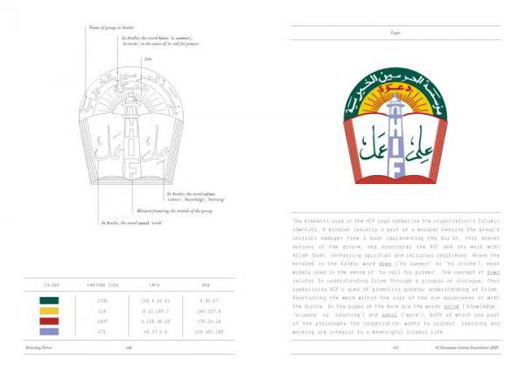

Following an excellent foreword from Steven Heller, the book lays out its terms with a forthright introduction followed a global map introduces the groups to be featured; 65 in total. In each case the mark comes first, redrawn and rendered in crisp vector lines with a full Pantone colour breakdown. Supporting each visual is a brief history and comprehensive interpretation of the symbolism and meanings expressed by the formal elements of color, image and typography.

With a subject this fraught it must have been quite a task for the authors not to get drawn into passing judgment, political or otherwise. But by adopting a pragmatic approach refreshingly free from earnestness they have managed to do so. Deconstructing each featured mark with clinical precision, they remain detached from any prejudice, maintaining an objectivity that leaves the reader free to understand and evaluate each group’s ideology and mode of operation.

A spread from Branding Terror, published by Merrel.

As one reads there is a feeling that we know this subject, that perhaps we have seen them all before. In some cases we have. This sense of familiarity may be bred by a certain visual vernacular common to all the featured marks. This vernacular in turn is commonly replicated, lampooned, synthesized, and fetishized across Western urban culture in the worlds of fashion, music, and street art. Yet despite this generalized familiarity, this still remains a private graphic world: these logos remain secret until the moment that their broadcast is required by events. As a result, only some of the marks are well-known, and even then have only been encountered through grainy TV footage and press photographs.

To be able to study the real thing, then, is an unusual opportunity for designers and historians. What we discover is that it is a rhetoric of idealism combined with a heavy dose of pageantry that drives these logos, and in turn the organizations that they represent. Together, they illustrate a fundamental truth about graphic design. Whilst some of the marks are theatrically elaborate, others are incredibly simple; where some are expertly created, others are crudely drawn; many employ cliché upon cliché: however, all apparently have the capacity to convey powerful messages.

A world emerges where aesthetic and graphic design skills take second place to connotation. The goal, first and foremost, is to persuade. To function, each logo must collate and objectify enough history and ideology to stir up an emotional response in the hearts of the observer.

Branding Terror is a tour de force of visual research with one fundamental flaw: its categorization as a design book. As one reads, one can’t help feeling that to talk about terrorism in pure graphic terms is to ignore the violence that has been and will be committed in its name, that a discussion of color references and font choices trivializes the subject.

Indeed the authors seem wary of this themselves as they make several attempts to diffuse this criticism and they are right to do so. If we are ever to understand how these organizations function, then their identity is arguably the best place to start. Perhaps then this is the real stock in trade of terrorism, that before any other activities, first and foremost a terrorist group is in the business of selling ideas?

But as ever with a subject this large, for every question answered another is asked and there was one that seemed to be ignored, one that would seem to undermine the intention of the book. It is a question that I suggest is fundamental to the study of branding: does an ideology create a logo or is it the process of branding, heralded by the mechanics of a logo, that ultimately creates a doctrine?

Branding Terror: The Logotypes and Iconography of Insurgent Groups and Terrorist Organizations

By Artur Beifuss and Francesco Trivini Bellini

Foreword by Steven Heller

Merrell Publishers Ltd (March 15 2013)