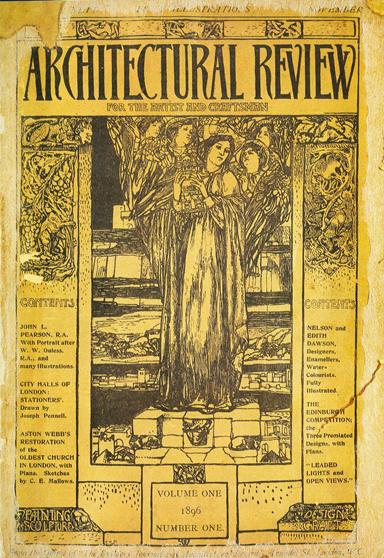

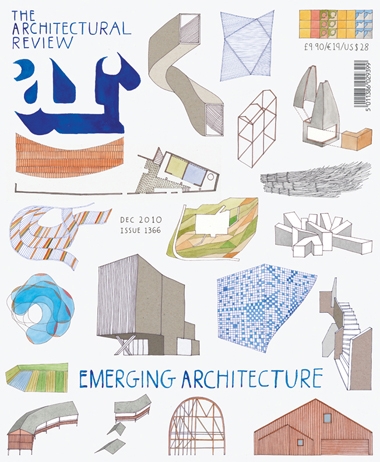

A bit of news: I am pleased to announce that I will be joining The Architectural Review as Associate American Editor. It's an honor to appear on the masthead of that distinguished publication, one with such a long tradition of excellence (Pevsner, Banham, etc) that it carries forward to this day. I've always tried to associate myself with organizations and individuals I admire, even when it hasn't been the most financially remunerative path. I should mention that this is not an exclusive arrangement; I'm certainly not giving up my home here on Design Observer.

As it is, my review of Yale's paired James Stirling exhibitions appears in the December issue of the Review. I hope these shows spur a bit of renewed interest in Stirling, who seems to me a bit of a forgotten man among the modern masters. Stirling's late-career postmodernism is a turn off to many contemporary designers, but to my mind he remains a generative figure. There has never been a better draughtsman. In his ambition to forge a new path for postwar architecture, he arrived at what I call an "architecture of assemblage, expressive of function and structure at once, with volumes broken into constituent parts, based on program. Whereas Le Corbusier talked conceptually about 'machines for living,' Stirling’s buildings seem like actual machines." Ada Louise Huxtable suggests much of the same in her column on the shows in the WSJ; It's always nice to have the dean of the profession affirm what you've written. Stirling is also the subject of a package of stories in Architect magazine, another positive sign that he is returning from the margins of history.

I also have a piece in the latest issue of Architect, an essay on the relevance of architectural biography that doubles as a review of Deyan Sudjic's fine new life of Norman Foster. This is a subject — architectural biography — that's something I think about a lot these days, as I work on my own bio of Philip Johnson. To wit: "Architecture is more than entertainment; it orders our lives and shapes our cities. Understanding the men and women who create it — their intellectual roots and the experiences from which they draw — would seem to be a reasonable imperative, now more than ever." If that reads as something of a self-justification, so be it.