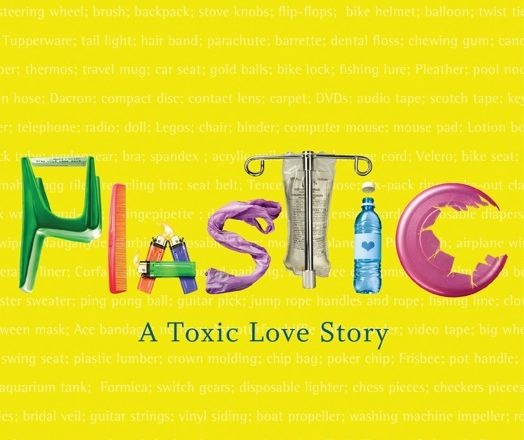

Cover of the book Plastic: A Toxic Love Story © C.J. Burton

In the 44 years since The Graduate’s Benjamin Braddock was advised that plastics were his future, the material has become enmeshed in our present. We exalt plastic as a synonym for credit and disparage it as the stuff of superficiality. Susan Freinkel’s new book (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) examines how a material that started off as an almost miraculous solution to many human problems has become a permanent, and in several ways pernicious, part of our lives.

Divided into stories of eight iconic plastic objects — comb, chair, Frisbee, IV bag, disposable lighter, grocery bag, soda bottle, and credit card — the book explores plastic’s environmental, monetary and global effects. Though the conclusion is dire, Freinkel doesn’t scold, but writes with equal parts humor and rigor.

Claire Lui: What made you decide to write about plastic?

Susan Freinkel: I live in San Francisco, a place where concerns about plastic have been brewing for years. So one day I decided to see if I could go 24 hours without touching anything plastic. The absurdity of that idea became immediately clear when, on the appointed morning, I walked into the bathroom and confronted my plastic toilet seat. New plan: I would instead spend the day writing down everything that I touched that was plastic. By day’s end I had a list of more than 200 items. I was surprised to realize how much plastic had become a part of my life without my even trying. And I was surprised by the variety of things on the list — from food packaging to my sneakers to the knob to our front door, which looked like brass but I discovered was actually plastic. Looking at that diverse array of stuff, I realized I had no idea what plastic is or where it comes from or the extent to which it is a problem. I figured if I was asking those questions, lots of others were as well.

Lui: How did you decide on the eight plastic items your book is built around?

Freinkel: I was looking for objects that would allow me to explore certain themes in the plastics story. For instance, I knew I wanted to cover the history of how early plastics were used to replace scarce natural materials. But I wasn’t sure what object would best express that history until I visited the late, great National Plastics Museum in Leominster, Massachusetts, and saw a display of gorgeous celluloid combs that looked like they’d been carved from ivory. Likewise, I wanted to explore the double-edged role plastics have played in medicine, making possible both great medical advances, while introducing potential new health risks. The blood bag embodied both. It revolutionized the way blood is collected and stored, but the material used to make it, vinyl, leaches chemicals that may act as hormone disrupters.

Lui: What were some of the other objects you considered focusing on and why did you ultimately choose not to include them?

Freinkel: I needed objects that had good stories attached to them, embodied a given theme clearly, and above all, were affiliated with companies that would give me access. So, for example, to describe the global production chain involved in making most plastic products, I wanted to use a toy. I initially hoped to write about dolls, but I could never convince either of the major doll manufacturers, Mattel or Hasbro, to cooperate. Wham-o, maker of the Frisbee, agreed to let me visit its factory in China.

Lui: In the book, there’s a sense that you yourself have been seduced by plastics at various points in your research. Can you talk about the love/hate relationship you allude to in your title?

Freinkel: Plastics are amazing materials, though that can be hard to remember when you’re looking at photos of seabirds with bellies full of plastic trash. But plastics freed us from nature’s limits and gave us an unprecedented ability to make things that we need and want – and for relatively little money. Over the decades, polymer engineering has gotten very good at manufacturing materials that do exactly what we need them to, whether that’s running marathons, stopping a bullet or keeping a shipment of lettuce fresh. Unfortunately, we’ve also used plastics to make a lot of low-quality and kitschy crap — think pink flamingos, dashboard Jesuses, quickly broken party favors. That stuff has diminished plastic’s reputation. As has the fact that we continue to use too much plastic for throwaway applications. The convenience is seductive, and yet our reliance on disposables is a problem given that the materials are engineered not to break down.

Lui: Has writing this altered your plastic consumption?

Freinkel: It comes down to lots of little changes: I carry reusable bags when I shop. I think harder about how products or food are packaged and will forego something if the packaging is just too much. My family likes fizzy water, so instead of buying it in bottles, we got a seltzer maker that comes with refillable cartridges and reusable bottles. I pack the kids’ lunches in reusable containers. I don’t own a microwave or cook much frozen food, but if I did, I would not heat them in plastic. I’m also much more diligent about recycling.

Lui: Do you have any tips for readers about how to lower plastic consumption in their own lives?

Freinkel:

1. Refuse single-use freebies: Bring your own bag when shopping. Carry a travel mug for your daily caffeine fix. Tell your waiter you don’t need a straw. Instead of buying bottled water, stay hydrated from reusable bottles made of metal or BPA-free plastic.

2. Buy in bulk when you can. Or at least opt for the larger containers over individual-serving sizes.

3. Reuse where possible: Give that sandwich baggie a week’s workout; use that empty yogurt tub for leftovers.

4. Use your purchasing power to support companies that are trying to use less packaging and healthier kinds of plastic.

5. Learn what you can recycle. Find out what plastics your community recycler accepts. Explore other recycling resources: UPS stores will take back shipping peanuts; many grocery chains will take used bags and plastic film; many office supply chains will take back used printer cartridges.

Lui: You live in San Francisco, which has an ambitious curbside recycling program. Having tracked the efforts of where San Francisco’s recycling goes (to China), there’s almost a sense of futility in the book — that no matter how well-intentioned our efforts, plastics still seem to multiply with negative side effects. Have I overstated your point of view?

Freinkel: I don’t think individual efforts are futile. Each time we buy or decline to buy something we are sending a message to its manufacturer. Collectively those messages can shift markets. It was a grassroots campaign that persuaded Clorox to start recycling Brita filters, and while federal regulators have not taken action on Bisphenol A, parents’ concerns were why manufacturers of baby bottles and sports water bottles shifted to plastics that don’t contain BPA. Recycling only works when there are ample supplies of used things to recycle and secondary markets to repurpose that stuff. The loop comes undone when individuals quit making the effort to see that their used stuff is recycled.

That said, there are limits to what individuals can do. For example, recycling has become the responsibility of taxpayers and municipal governments, when more of the burden ought to be borne by the manufacturers and brand holders that put packaging and products into the marketplace. In countries that have passed laws requiring manufacturers to be responsible for the disposal of their products and packaging, guess what happens? The companies use less packaging, they make their products and packaging out of materials that are more easily recycled, and the country’s overall recycling rates shoot up.

Lui: What are some of the class issues connected with plastics?

Freinkel: The class issues cut in various directions. Low-cost plastics have made consumer goods far more broadly available to people of modest means. However, they’ve also enabled a throwaway lifestyle, which can have different meaning for the rich and the poor. The plastic industry has often fought attempts to levy fees on plastic bags by arguing that these fees would be a burden for the poor, who would have a hard time paying for bags every time they shop. There may be a tiny kernel of truth in that, yet it also assumes people would have to pay for new bags every time they shop. And low-income shoppers are the very folks who have a greater incentive to reuse bags in the first place. When you’re poor, reuse isn’t a luxury; it’s a way of life.

At a broader level, one of the disturbing developments over the past decade or so is how the West has exported a disposable lifestyle to the developing world, where the infrastructure is even less capable of dealing with the tidal wave of single-use bags, drinking straws, lighters and the like.

Lui: On a related note, what role does plastic play in other countries?

Freinkel: While the U.S., Japan and Europe historically were the biggest consumers of plastic, the developing world is poised to catch up. Consumption of plastic is rising fast in China, India and Africa and is expected to keep growing. In light of that, one forecast envisions global plastics production increasing fourfold by 2050, to almost 2 trillion pounds. There’s no reason the developing world shouldn’t enjoy the same solid benefits plastics have brought to the West – in cars, electronics, medicine etc. But if, as now is the case, we continue to pour half of our plastics produced into disposable goods, then I fear the world truly will choke itself to death on its trash.

Lui: Ultimately you conclude that government must intervene to decrease our use of plastics. How might that happen in today’s political climate, given the costs and concerns among many over any form of government intervention?

Freinkel: It is disheartening when you see news like the Congressional leadership’s decision to get rid of compostable food ware in the House dining room because the composting program was too expensive. But I actually think interest in sustainability cuts across political lines. And there are a lot of major companies that are recognizing that it’s in their economic interest to recycle more, use less packaging, and cut their material and energy waste. Doing eco-good, they’re seeing, is often also good for the bottom line. For instance, there’s a group called the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, which was organized to encourage adoption of cradle-to-cradle principles, and it counts as its members some of the world’s biggest, most influential companies. Likewise, Wal-Mart’s commitment to reducing its own packaging and carbon footprint is having ripple effects throughout the global supply chain. These initiatives are an important start, though I doubt we can depend solely on the free market to deliver us from our plastic follies — otherwise we wouldn’t need the bottle bill laws that the beverage industry has so bitterly fought.

A version of this interview first appeared on The Living Principles and is reproduced by the editors' kind permission.