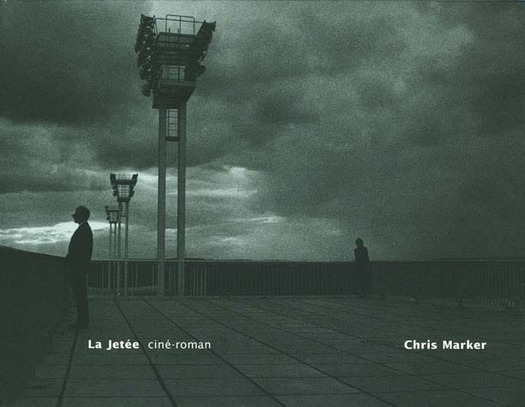

For years, I've owned a copy of La Jetée, a book about the film by Chris Marker, the experimental filmmaker. Designed by Bruce Mau and published by MIT Press/Zone Books in 1993, this is one of those design books that has ascended into the realm of rare bookdom (like Learning from Las Vegas); not a single copy is offered online today, and a seasoned dealer would catalogue a fine copy for over $500, even perhaps over $1000. While Zone was the project where Mau first established himself as an intellectual designer, these were generally text-laden monographs for an esoteric scholarly audience. La Jetee, the book, is different: a photo-novel ("ciné-roman") with no text except for captioned narration. I have always thought of it as the mother of the full-bled-photography thing that Mau is known for, and that has since become a frequent conceit in contemporary design publishing.

Then I saw the film. I love the book, but it becomes only a book in the face of its original media. I remember more of this movie than the previous hundred movies I've seen. La Jetée is constructed in still images; it is a movie of photographs. The implications of this, and the statement — "I remember more..." — are enormous.

La Jetée is a 28-minute experimental film made in 1962. Though I studied film in college, I managed to miss it. It shows up as a trendy icon of cultural studies, like Jean Baudrillard or Guy Debord, in student bibliographies (frequently in those I see from Yale); in new histories of the cinema; and even through Netflix, where I finally encountered it. La Jetée is its own special occasion. Scenes are inspired by Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958). And it inspired the story of 12 Monkeys (Terry Gilliam, 1995). I have seen both films a couple of times and remember numerous segments. Yet, I have the most precise and vivid memory of almost every image in La Jetée.

La Jetée is a story of memory. As described by film critic Jaime Christley: "it's present-day Paris, where a young boy sees a beautiful woman at an airport, and then sees a man die of a gunshot wound from an unknown assailant. Years later, following an apocalyptic disaster that has driven a decimated mankind into underground bunkers, the boy — now grown — is afflicted by his memory of the beautiful woman so strongly that government scientists wish to use it as a means for time travel, with the hope of finding a key to restoring the world to its former condition. Naturally, he meets the woman and falls in love with her."

This description of the narrative downplays the impact of the imagery. His time travel occurs through the most makeshift of experiments; he becomes a monster resembling nothing less than the madness portrayed in the photographs of Joel Peter Witkin. As a man encountering his lover, one can only think of the films of Claude LeLouche, which would come years in the future. In our time, one is reminded especially of the Matrix. In 28 short minutes, and a few hundred still images, La Jetée competes in my mind with the most dramatic three-part, six-hour science fiction epic that Hollywood can serve up.

The photographer as editor as designer as movie-maker is all contained within the genius of La Jetée. As it stirs our emotions with memories, it also makes possible the construction of a never-to-be forgotten narrative sequence. It's so simple. It's the ultimate visual essay, the epic novel told in the most minimal and constrained number of images.