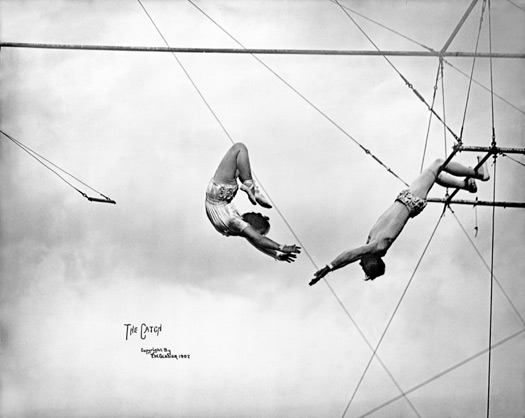

Maude Banvard, The Catch, Brockton Fair, Massachusetts, 1907. Started in 1874, the Brockton Fair’s purpose was to encourage agriculture. By the turn of the 20th century, the four-day event included agricultural exhibitions, musical concerts, horse shows, and a stage show. The Flying Banvards, a troupe of champion aerialists, performed “amazing feats on the Flying Trapeze” as part of the outdoor show.

The elaborately produced new book Circus: The Photographs of Frederick W. Glasier, showcases the rediscovered work of the great American photographer Frederick W. Glasier. Glasier made extraordinary photographs of the American circus during its heyday, 1890-1925. A contemporary of such recognized masters as Eugene Atget in Paris, August Sander in Cologne and Ernest J. Bellocq in New Orleans, Glasier is arguably in that class of the greatest practitioners of the medium. Below is an excerpt from the book, written by Luc Sante, accompanied by a slideshow of selected images.

Frederick W. Glasier was born in Adams, Massachusetts, in 1866, to middle-class parents — his father, a Civil War veteran, was employed in different aspects of the local textile industry. After early employment as a jeweler, Glasier moved to Brockton, south of Boston, at the age of 30, and two years later was listed in the city directory as a photo printer. His first dated and copyrighted pictures appeared the following year, and the year after that, 1900, he was listed in the directory as a photographer. What is recorded of Glasier’s subsequent career is if possible even sketchier. He published a souvenir guide to the town fair in 1905, and was intermittently listed in the directory as a publisher. In 1927 his wife issued a pamphlet describing the lantern-slide lecture series the two of them gave to church groups and the like. Glasier produced copyrighted images up to 1926 and dated ones up to 1934. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1950, at the age of 84. And that is virtually all we know aside from what can be inferred from the images themselves.

The elaborately produced new book Circus: The Photographs of Frederick W. Glasier, showcases the rediscovered work of the great American photographer Frederick W. Glasier. Glasier made extraordinary photographs of the American circus during its heyday, 1890-1925. A contemporary of such recognized masters as Eugene Atget in Paris, August Sander in Cologne and Ernest J. Bellocq in New Orleans, Glasier is arguably in that class of the greatest practitioners of the medium. Below is an excerpt from the book, written by Luc Sante, accompanied by a slideshow of selected images.

Frederick W. Glasier was born in Adams, Massachusetts, in 1866, to middle-class parents — his father, a Civil War veteran, was employed in different aspects of the local textile industry. After early employment as a jeweler, Glasier moved to Brockton, south of Boston, at the age of 30, and two years later was listed in the city directory as a photo printer. His first dated and copyrighted pictures appeared the following year, and the year after that, 1900, he was listed in the directory as a photographer. What is recorded of Glasier’s subsequent career is if possible even sketchier. He published a souvenir guide to the town fair in 1905, and was intermittently listed in the directory as a publisher. In 1927 his wife issued a pamphlet describing the lantern-slide lecture series the two of them gave to church groups and the like. Glasier produced copyrighted images up to 1926 and dated ones up to 1934. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1950, at the age of 84. And that is virtually all we know aside from what can be inferred from the images themselves.

He seems to have traveled with the Barnum & Bailey Circus for a while, and maybe later with the Sparks Circus, and may have journeyed to the west, although certainly the better part of his photographs of Native Americans were taken in studio settings and could just as well have been made on the east coast. According to Ringling Museum curator Deborah Walk, Glasier affected the look of a westerner himself, sporting a Stetson hat, boots, a leather jacket, and whiskers in the Imperial style favored by Buffalo Bill, and adds that his equipment included an 8 x 10 King view camera with a Thornton-Pickard shutter. We can also suppose that in the years between and after his circus and wild west show engagements, Glasier worked as a typical studio photographer, producing images of weddings and christenings and graduations and store openings. Beyond the necessity of earning a living, his pride in his work constituted his only reward. He could barely aspire to recognition, let alone fame or the esteem of posterity.

And yet his photographs exude a kind of ambition that does not require outside endorsement. Glasier mastered a whole world, as if he were a novelist. Rather than specializing in a single means of approaching that world in his photographs, which is what might be expected of a photographer today, he adapted himself to the task at hand, perfecting different approaches for different aspects of the subject. Some of these approaches are obvious to the task of publicizing a show, and we have seen versions — lesser ones, generally — by other hands: the group portraits, the static demonstrations by acrobats and contortionists, the action shots of tightrope walkers and diving horses, the portraits of animal trainers with their animals, the panoramic renditions of the big top and of the circus parade. But then there are other, less obvious sorts of pictures, which seem less certain to have been dictated by a contract, particularly those which record the backstage activity. In those pictures Glasier seems almost to be functioning as a photojournalist, one who is assigned to cover a phenomenon by immersing himself in it and taking pictures ad lib — although the notion of the photojournalist lay some decades in the future, and is barely conceivable for someone operating a view camera making impressions on glass plates. It is clear, in any event, that Glasier’s mandate was broad and probably determined by himself, and that his range of methods and range of subjects complemented one another. While a certain amount of fluidity — rather than a personal style, rigidly defined or otherwise — was demanded from the commercial photographer of a century ago, Glasier’s mastery of each of the forms in which he worked was absolute, as if he became a different photographer for each mode he took on.

Excerpted from Circus: The Photographs of Frederick W. Glasier, by Luc Sante, Peter Kayafas and Deborah Walk. Essay copyright © Luc Sante/Eakins Press Foundation, 2009. Published by Eakins Press Foundation. For more information visit www.eakinspress.com. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. All photographs by Frederick W. Glasier are copyright © Eakins Press Foundation/John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, 2009.