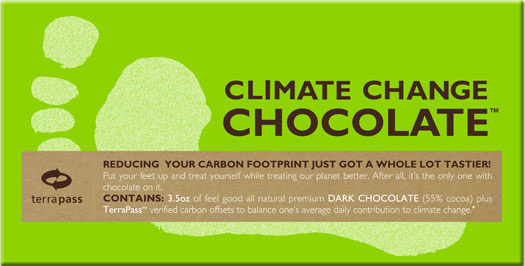

In this eco-conscious age, consumers have many ways to be sustainable. You can swap incandescent light bulbs for energy-saving compact fluorescents or exchange the squeezable Charmin for toilet paper made of recycled post-consumer content. Or you can buy Climate Change Chocolate, a 3.5-ounce confection that, for $4.95, offsets 133 pounds of carbon dioxide — the average American’s daily carbon impact on the planet. “It’s a great way to treat yourself while washing away your sins,” says John Edson, president of Lunar Design, which created the chocolate bar for San Francisco–based TerraPass, a company that develops carbon-reduction products.

Enjoying a chocolate buzz might appear to be a frivolous way to combat global climate change. But for companies like TerraPass, candy is one of many ways to educate and reward consumers who buy carbon offsets. That’s critical because unlike touting a light bulb or peddling organic food as part of a sustainable lifestyle, selling the concept of carbon offsets presents designers and marketers with a hurdle: “Offsets are intangible and hard to explain,” notes Pete Davies, president of retail at TerraPass.

In general, a carbon offset is a financial instrument aimed at lowering carbon dioxide emissions, the main cause of global warming. Projects that reduce emissions – such as a wind farm – can sell offsets to finance their development (every ton of reduced emissions results in the creation of one carbon offset). Individuals and businesses can buy into this cycle to offset their carbon production by funding carbon-reduction projects. The average American emits around 50,000 pounds of carbon dioxide annually (if you include your home, car and airplane flights) and carbon offset programs have been heavily promoted by retailers such as The Whole Foods Market.

To ease consumers into thinking about offsets, a carbon calculator on the TerraPass website assesses your daily carbon production — and what you abuse when flying or taking the car. The damage can be undone with individual TerraPass offset packages ($29.95 for a year’s hybrid car driving, for example, or $50.65 a year’s flying). Getting married? The carbon created by your nuptials — from the flights taken by guests to the energy used in hotel rooms — can be calculated and purged by buying offsets.

Since its launch in 2004, TerraPass has offset about 1.4 billion pounds of carbon dioxide through various marketing initiatives. These have evolved from an initial effort to sell road passes for pollution caused by driving to flight offsets and passes for the home, which came with rewards like a fridge magnet and a plastic bag dispenser made from recycled soda bottles.

But in 2006, Davies recalls, TerraPass was approached by Whole Foods Markets about developing a carbon offset product that could be displayed on a grocery shelf. In turn, TerraPass asked Lunar — the international design firm that had worked on its branding and website — to develop some ideas. Lunar’s list included bumper stickers and raised chrome emblems for cars, but then narrowed the choices to impulse purchases under $10, such as daily offset water priced around $1.49; truffles representing a week’s offset for $9.95 (with a fridge magnet thrown in); and a chocolate bar co-branded with TerraPass with energy-saving tips on the wrapper. Chocolate won out, because it was size-appropriate and a good match with a daily offset — as well as being something special to eat, compared to water, which is a necessity.

Such marketing tactics are ammunition to carbon offset critics. “Allowing polluters to buy their way out of reducing pollution means that they won’t shift any time soon to cleaner processes or technologies,” wrote representatives of Environment America, a federation of state-based, citizen-funded environmental advocacy organizations, which supports moves to reduce global warming, in a press release. “Instead, they will offset their known pollution with less-certain reductions from things like tree-planting projects or pollution reductions overseas.” Consider British band Coldplay’s involvement in 2006 with the planting of 10,000 mango trees in India to offset the production and distribution of its album A Rush of Blood to the Head. Most of the trees eventually died, reportedly due to neglect and a poor forest management infrastructure.

Supporters argue that offsets, while not the only way to eliminate global warming, are effective at reducing the environmental impact of consumption. “If our goal is to reduce carbon emissions as efficiently as possible, offsets make perfect economic sense,” wrote Robert H. Frank, a Cornell University economist, in a May 2009 op-ed piece in The New York Times. Some cities, like San Francisco, agree: In conjunction with Cisco Systems, it recently launched a web-based carbon footprint–tracking tool that enables citizens to calculate carbon emissions by zip code. Carbonfund.org, a nonprofit provider of carbon offsets based in Silver Spring, Maryland, has tried to address criticism of carbon offsets by establishing strict guidelines for verifying and certifying carbon-free products and setting up third-party standards and auditing of offset projects in which it invests, including reforestation, renewable energy and energy efficiency.

CarbonFund.org also works with some 1,000 businesses — like the airline JetBlue - to establish carbon-offset programs, and it encourages donors to choose their own projects under a trademarked program called Your Carbon, Your Choice. Moreover, it is moving in a new direction with carbon-free certified products – such as Motorola’s Renew phone, the first carbon-free certified cell phone. Carbonfund.org worked with Motorola to determine the carbon footprint of its new phones, and on ways to reduce the footprint, including the packaging and materials (the phone’s casing is made from recycled water bottles).

Moreover, Motorola donates to Carbonfund.org projects based on a percentage of quarterly sales figures, offsetting the energy required to manufacture, distribute and operate the phone. Another certified product is Florida Crystals sugar, which was rendered carbon neutral through the company’s own production methods and supply of renewable energy — rather than the company buying offsets.

The goal is to expand consumer choice in going carbon neutral by letting consumers buy offsets for direct emissions (from your home or car) as well as carbon-free certified products. The label also wins kudos for the companies, which gain a green halo. “Consumers respond to efforts by companies to understand their environmental impact and take action,” says Ivan Chan, Carbonfund.org’s spokesman. “The label represents both – commitment and action.”

Still, selling an eco-friendly chocolate bar reminding consumers to “hang your wash outside on a nice day instead of using a clothes dryer” doesn’t convince some skeptical marketing experts about the benefits of carbon offsets. “They are a way for the guilty to pay for spiritual absolution instead of changing their questionable behavior,” notes Brian Collins, chief creative officer of New York branding agency Collins. “Offsets take our eyes off the real problems we need to confront now.”