At tonight's AIGA gala, Dan Friedman, among others, will be posthumously awarded the AIGA Medal.

This week we have been publishing a personal remembrance of Dan by his friend Christopher Pullman. Part 4 today.

Other installments in the story are here, and the final installment will be published tomorrow.

++

This week we have been publishing a personal remembrance of Dan by his friend Christopher Pullman. Part 4 today.

Other installments in the story are here, and the final installment will be published tomorrow.

++

A new chapter in my relationship with Dan Friedman began in 1974, the year Esther and I moved from New Haven to a little apartment in Cambridge. I began working for WGBH and Esther took a position with the architecture firm, Cambridge Seven. Simultaneously, Dan left for New York and we fell out of touch.

Yale liked its graduate teachers to be practicing professionals. People like Dan felt the ironic pressure to make it in the big time design world in order to be fully respected as a teacher. So Dan left teaching and joined Anspach Grossman and Portugal to prove his mettle. He took on one of the huge, archetypal corporate image programs of the 1970s for Citicorp with scant experience with a project of this scope and political complexity. It was a monster.

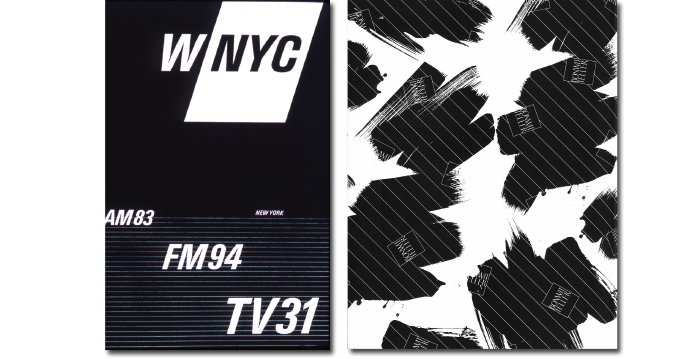

His meticulous vision for the global bank was codified in elegant posters and a thick manual creating templates for every imaginable application.

Next was an invitation to join the new Manhattan office of Pentagram, the classy London-based studio. Although Dan turned out a number of elegant projects for Pentagram, it wasn't a perfect fit.

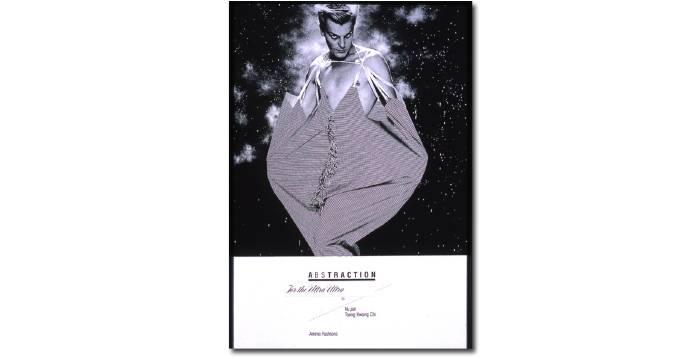

Instead of bringing in the big Citicorp-style clients to Pentagram, he gravitated toward smaller, unprofitable—but enjoyable—freelance jobs for his friends in the fashion industry.

This put him at odds with Pentagram’s commercial studio model. He began to be much more inspired by the late night club circuit than his day job as a designer and in a few years he left Pentagram for good. Then everything changed.

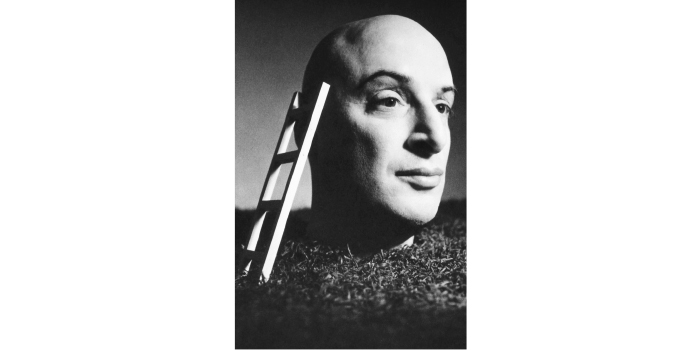

He shaved his head, purged his body with a macrobiotic diet, openly embraced his homosexuality and joined the downtown art scene.

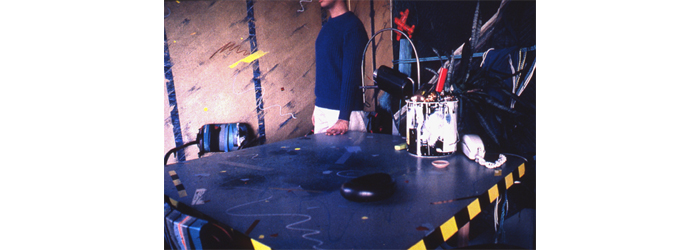

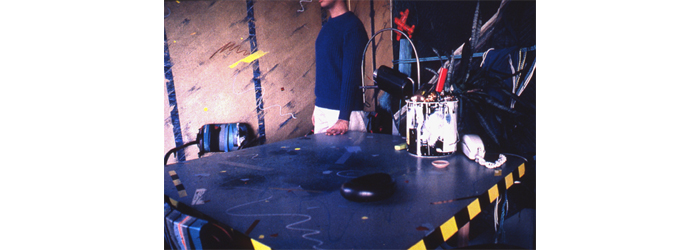

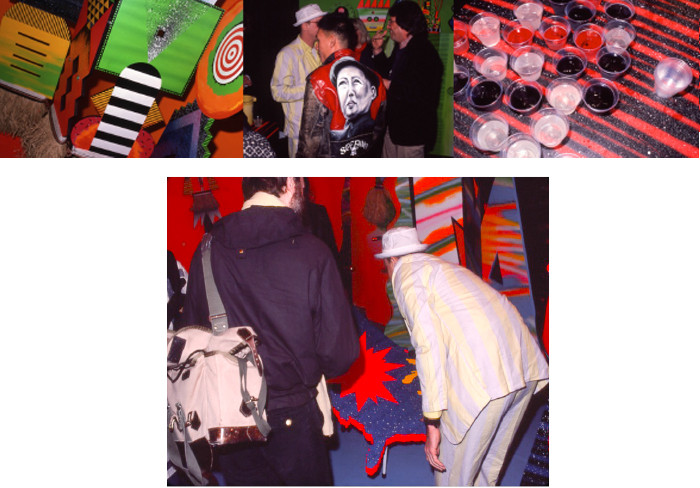

In an essay in Dan’s book, educator and curator Steven Holt had this observation: “As Friedman began to pursue projects of personal meaning rather than professional interest at the end of the 1970s, his life increasingly took on the dimensions of an experiment rather than a career.” Nowhere was this more obvious than in his apartment, a nondescript, one bedroom on the 15th floor of Two Fifth Avenue. For over a decade, beginning in the late '70s, he transformed, almost daily, this domestic space into a laboratory for experimentation with color, form, materials, and meaning.

After years of only sporadic news from Dan, one Sunday morning in 1978 I picked up the New York Times Magazine and there he was.

In the article he explained it this way: “I have for many years used my home to push modernist principles of structure and coherency to their wildest extreme. I create elegant mutations, radiating with intense color and complexity, in a world that is deconstructed into a goofy ritualistic playground for daily life.”

For me, these incredible environments are among his most remarkable work, spawning ideas for screens, furniture, and assemblages.

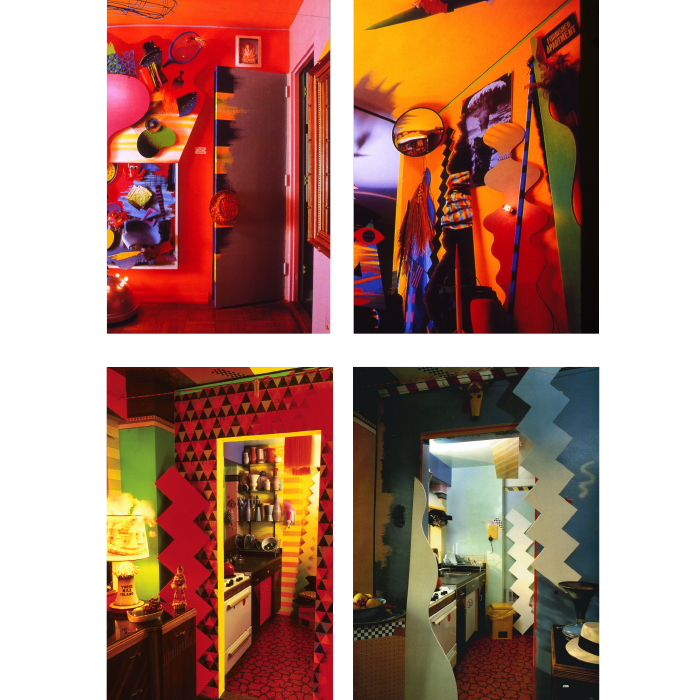

His inspirations had to include the rude, energetic tagging of the New York subway cars, the trash structures encountered on trips with his buddies to the Caribbean as well as the deep memory of Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau, a similar decade-long to turn a domestic environment into a work of art.

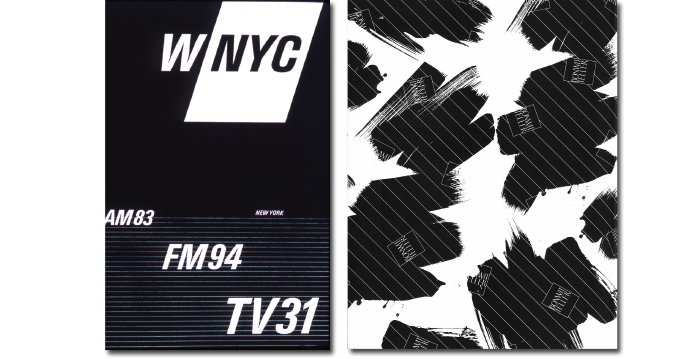

These influences seemed to tap into the deeper cultural shift being felt at the beginning of the 1980s from neat to messy, from newness and originality to appropriation and transmutation. The same shifts brought us the beat-up fantasy worlds of Road Warrior and Blade Runner, both of which came out in 1982. Energized by his new life, Dan entered a hugely productive period making old stuff new, endowing dumb objects with new meanings and turning trash into “tribal objects of domestic utility.”

His apartment experiments led him to revive the ancient form of the folding screen and spin out a witty succession of “ridiculously practical” fantasy furniture.

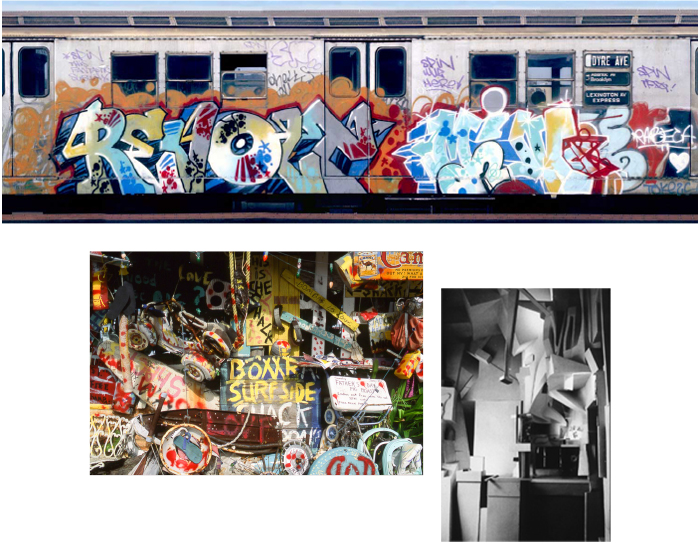

For large-scale wall sculpture and vivid installations he employed the art of assemblage, a trusty Modernist device for managing visual diversity and altering meaning through bizarre juxtaposition. By the early '80s Dan had begun to fill galleries with these post-nuclear evocations.

In 1984 he phoned out of the blue, with an invitation to his opening at the Fun Gallery. And there I found the new Dan, fluorescent in his striped Dayglo suit and pork-pie hat, smiling amid a sea of big hair and aggressive personas.

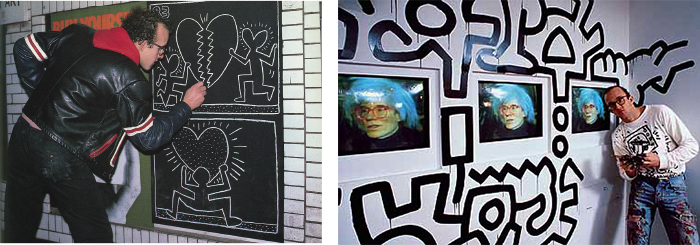

In just a few years Dan had made good on his personal vow to experience a whole new side of culture, one which he found full of energy, fantasy, and optimism. His transition into the world of art was facilitated by his friendship with Keith Haring, a young, brash kid from rural Pennsylvania, who took New York by storm in the beginning of the '80s.

Like Andy Warhol a generation earlier, Haring was so naturally talented, so in tune with the culture, so charismatic, energetic and prolific, that he drew around him like-minded eccentrics. Within this circle were talents of all persuasions: musicians, fashion designers, poets, performance artists, DJ’s, filmmakers, and photographers. “An eccentric,” Dan wrote, “is one who devotes his or her entire persona to willfully, creatively, and positively expanding our view of the world.” This was a definition that Dan also employed to help explain himself.

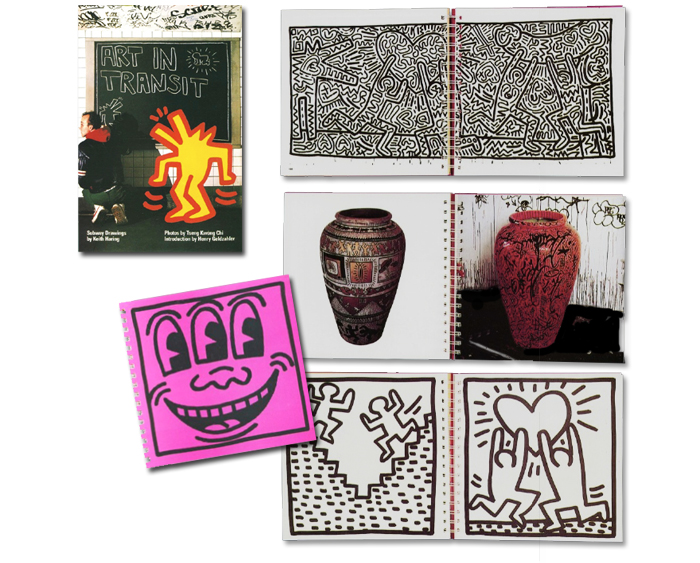

Dan was welcomed into Keith’s circle as a kind of wise elder statesman. Haring was everything Dan was not—facile, spontaneous, loquacious, and unschooled in traditional design—and their mutual admiration fueled both an intimate friendship and a professional collaboration on the catalogs, products, and books that were the Pop Shop by-products of Haring’s sudden fame. These projects helped make Keith a household name and, coincidentally, assured Dan that his skills as a designer were still valuable.

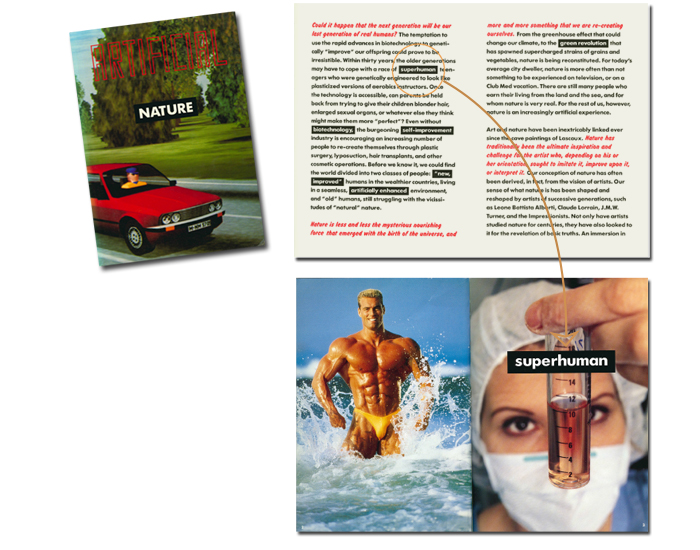

During this period, Dan was able to bridge his fields of design and art through a series of publications for the gallery owner and curator Jeffrey Deitch. For two different shows—Artificial Nature and Post Human—Deitch invited Dan to create visual essays that served as an introduction to the exhibitions. Dan parsed Deitch’s essays, isolated key words and phrases, and then paired them with provocative images that he researched. These juxtapositions were full of irony and energy, bringing a new level of meaning to Deitch’s words, a testament to how tuned in Dan was, in his new life, to the images, art and ideas of popular culture.

And when the art community became engulfed by the AIDS crisis, he devoted his skills as a designer to AIDS activism, having lived for years in the shadow of the disease himself.