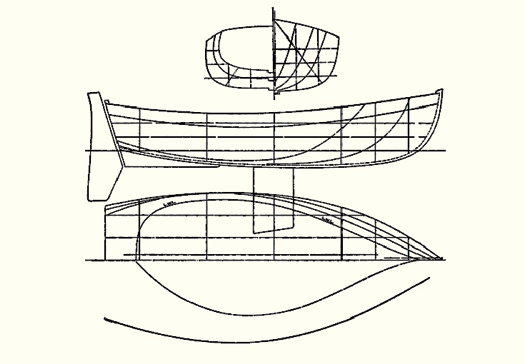

Diagram from Atkin Boat Plans

“The last few decades have belonged to a certain kind of person with a certain kind of mind — computer programmers who could crank code, lawyers who could craft contracts, MBAs who could crunch numbers. But the keys to the kingdom are changing hands. The future belongs to a very different kind of person with a very different kind of mind — creators and empathizers, pattern recognizers, and meaning makers.”

So wrote Daniel Pink in A Whole New Mind back in 2005. Now, some might quibble that in an era where engineers are trading themselves like over-hyped stocks, it's clearly not the case that one group will necessarily replace the other. But the concept of the rising importance of the creative class has certainly become more widely accepted in the six years since that book (subtitle: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future) was published.

What hasn’t become so clear is how exactly the new meaning makers will ever arrive on the scene. Worse, it’s not clear that the obvious crucibles from which our creators and empathizers might emerge, the world’s universities, are at all capable of producing those with the different kind of mind necessary to lead in the complex new reality.

In the past few years, there have been interesting attempts from within both business and design schools to elevate the potential of design and creative thinking as drivers of differentiated value. There’s the d.school at Stanford, which offers design-driven classes to students of any department at the university. Then there’s the MBA in Design Strategy at the California College of Arts, or the M.Des/MBA joint program offered by the Institute of Design and the Stuart School of Business at IIT. Alternatively, the likes of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and Yale School of Management have implemented design-related courses as part of their traditional MBA education. Similar initiatives are being implemented in various universities around the world.

Yet there are still relatively few graduates from these programs, and their impact and efficacy remain inconclusive. As my colleague Larry Keeley, cofounder of Doblin and longtime teacher at both IIT’s Institute of Design and Kellogg School of Management remarks, two years of graduate school can only do so much. “Humans have an absorptive capacity limit that’s finite,” he says. “We can’t expect people to master everything that has to do with business and design at the same time.”

Last year, Sara Beckman, a longtime professor at the Haas School of Business, part of the University of Berkeley, was tapped to give a new course, Problem Finding, Problem Solving, to all 240 first-year graduate business school students. It was her (and her dean's) attempt to introduce a design-based process to those more used to drawing their conclusions from data-heavy spreadsheets. Their aim was to prompt the students to start thinking about problems in a wider context, as well as to teach them techniques to generate and evaluate potential solutions.

The class was a disaster, with Beckman getting the worst student scores in her 25 years of teaching at Berkeley. Her conclusions for why she received such a drubbing are illuminating when thinking about the challenges of trying to create the thinkers needed in our new world.

For one thing, at a very basic level, business school isn’t designed for design. The “I speak, you listen” podium format and the theatrical tiered-seating of traditional academia is the diametric opposite of the design school process of all-hands-on-desk, of creating multiple prototypes and collaborating actively. How can students possibly work together effectively if talking to each other results in cricked necks and beyond-awkward group dynamics?

And yet, this practical problem neatly mimics a tension present in the larger corporate world. Business isn’t designed for design, either. How many corporate meeting rooms are free for teams to cover in scrawled thoughts and half-baked ideas? And how many of them are part of a wider system in which rooms are booked in half hour increments, and please take your coffee cups with you when you’re done? There’s a reason that design-based innovation firms (like my firm, Doblin) have dedicated case team spaces in which team members can simmer in specific problems for weeks at a time, and it’s not because design is an undisciplined mess. There's method to the apparent madness: It’s from this rich stew of scrawled half-ideas and whiteboard daubings that unexpected insights emerge. And there’s a reason this happens less often in a corporate context: logistics managers have got better things to do than indulge what they have no reason to see as anything but unstructured lunacy.

As Beckman realized after she’d read the scathing comments from her graduate business students, not only were they not used to the process of drawing ideas on whiteboards or acting on hunches, they were actively hostile to it. “I’d hear comments like, ‘the company I worked for would never use Post-it notes’,” she says.

Here’s the thing: The tactics Beckman was teaching are the most superficial aspects of a design-related education, the ones it is even vaguely possible to fit into the space of a semester-long course in business school. If students struggle with even these straightforward tools of creativity, it seems a stretch to imagine they might also learn respect for design’s ability to add value outside of its own department. Yet Beckman also notes that some of the students approached her after the course was over to say that the techniques they'd learned had stuck in their heads and were, in fact, influencing their thinking. It took longer than a semester, but they were indeed beginning to think differently about solving problems.

Other business school programs report some success of creating design evangelists among their students. At the recent Design Challenge held at Rotman, eleven student teams from the business school entered the competition. Yet the mostly unspoken suspicion of the apparent frivolity of design-related strategic techniques is a deeply held stigma: business and design leaders need to address this directly if they want to engage the new minds — and modes of thinking — that will be key to their companies' ongoing success.

Design school leaders, in turn, need to educate graduates who can speak the language of business with at least some fluency. I spoke to a number of design school heads for the purposes of this piece and a presentation I gave at the Rotman competition. One of them waxed lyrically about his school’s deep commitment to the real-world demands of business, describing a project in which a student had stitched the principles of supply and demand into a quilt. No disrespect to quilt makers, but I don’t know that this represents the vanguard of change that Pink and others had in mind.

At times it seems worse than well-meaning cluelessness. Some design schools seem to promote suspicion of the business world as an unspoken matter of course. Headlines of the past few years hardly contradict distrust of the corporate status quo, yet producing students who are for the most part unaware of how the world (or the balance sheet) works seems enormously irresponsible. Another design school chief I spoke to was acid-tongued in his disdain for both the corporate world at large and the recent rise of “design thinking” as a practice within business and business schools. Instead, he dreamily outlined a world in which designers reject the faceless corporate machine, and instead act as lone entrepreneurs in pursuit of their own destiny.

Running a solo design shop is a noble pursuit. But entrepreneurs have to exist in the world as it stands, too, and that involves learning about its current means and structures. After all, you can only reject what you understand. If designers want to make a genuine impact on the world, they’d do well to learn how to navigate big companies and figure out how to articulate their value to the people who run them.

We currently roil in an awkward interregnum as the existing system teeters even as anything that might replace it remains untested at scale. The need to produce Pink’s creators and empathizers, pattern recognizers, and the meaning makers who will be able to manage uncertainty and implement large-scale change is more urgent than ever. The current tactic of passive/aggressive rejection by both sides of the business/design divide smacks of onlookers nudging each other and pointing at the band playing as the Titanic sank. Instead, we need both sides to stop their familiar, favored activities, put down their defenses, work together effectively and start plugging holes. Better still, we need them all to figure out how to build a whole new boat.