The space between what we hope to achieve in our lives and the realization of those desires is riddled with contradiction and confrontation. One role of design is to help people navigate the latter in order to manifest the former. Designers are very good at this when those we’re designing for already hold a certain station in life. We help them build on their positions of belonging so they can become what they aspire to be. Yet, except for notable exceptions, we have not yet found our stride in designing for those still struggling to belong. And because a large percentage of designers are buffered from the worst systemic entanglements of exclusion, inequity and racism, the thresholds that separate those who have the luxury of becoming from those who still struggle to belong are so invisible to us as to be non-existent. This implicit bias, when acted upon a thousand times a day in a thousand design studios around the world, has inarguably reinforced entrenched power structures like white supremacy.

As a designer who’s made a career-long effort to challenge the status quo in our industry, I myself have made assumptions as a white male that have revealed blind spots in my own privilege. And in certain situations, I’ve unwittingly opted for more ‘reasoned,’ ‘fair-minded,’ or ‘less controversial’ framings of concepts, opportunities, and challenges. The fact that these habits of mind eluded me at those times doesn’t reduce their insidious nature. As a way to illustrate this, I’d like to share a recent example.

First, some context.

In my teaching in the Design for Sustainability program at SCAD, and in my running of a non-profit organization, I’ve embraced the Capabilities Approach as a guiding framework. And in my most recent book, Designing with Society, I suggest that design for social impact can be thought of as designing capabilities because human capabilities as defined by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum are the desired outcome of our efforts. For those unfamiliar with the Capabilities Approach, it’s worth quoting philosopher Martha Nussbaum at length:

“The Capabilities Approach can be provisionally defined as an approach to comparative quality-of-life assessment and to theorizing about basic social justice. It holds that the key questions to ask, when comparing societies and assessing them for their basic decency or justice is, “What is each person able to do and to be?” In other words, the approach takes each person as an end, asking not just about the total or average well-being but about the opportunities available to each person.” She articulates how the Capabilities Approach is pluralistic at heart, ‘commits itself to respect for people’s powers of self-definition,’ and is, ‘concerned with entrenched social injustice and inequality, especially capability failures that are the result of discrimination or marginalization.” While the Capabilities Approach is commonly understood in international development circles, it’s in large part absent in the field of social impact design.

And now the blind spot.

In a discussion about capabilities and design with our Design for Sustainability thesis students, I once drew a sketch on the whiteboard that defined a liminal space between the individual and the various hierarchical forces of their social surroundings. In that space I wrote down the four levels of cultural competence: cultural knowledge, cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, and cultural competence (figure 1). The point I was clarifying was that designing for a minimal level of central capabilities for all members of society involved facilitating the adoption of cultural competence in those who hold places of power in society. Nussbaum’s idea of ensuring a minimal level of central capabilities for all members of society is at the heart of her framing of social justice. And from a design perspective, the idea is to focus not on those who have already attained privilege, but on those who must struggle against what Jonathan Wolff and Avner De-Shalit call corrosive disadvantage. So, the framing of a ‘minimal level’ of capabilities does not reflect a lack of ambition as much as a point of clarification about who and what we should be focused on (gainful employment before capital gains, affordable housing before second house, etc.).

The visualization helped crystallize a core aspect of the Capabilities Approach. It clarified how capabilities are substantive freedoms that primarily reside within the negotiated space between individuals and the larger social realm, rather than solely within individuals themselves (there’s a longer conversation here about Nussbaum’s internal and combined capabilities for another day). It wasn’t an inaccurate picture. It just wasn’t a complete one. That negotiated space is rife with things like racism and white fragility and stopping at cultural competence, in retrospect, was sugarcoating the harsher realities. And if designers—people in this world whose very task it is to visualize the invisible and to concretize the intangible—cannot overcome the blindness of their own privilege in order to portray the entirety of the conditions they are aiming to address, then what hope do any of us have in effectively fighting for social justice? This is no small shortcoming. If we neglect to consider the hidden patterns responsible for driving the problematic behaviors of a system that we aim to change, the end result is an insidious delinquency. Our efforts perpetuate the very behaviors we hope to challenge by neglecting to articulate their presence. It’s not the equivalent of saying your uncle struggles with sobriety rather than saying he’s an alcoholic. It’s worse by an order of magnitude.

It took the events of this past spring in the US in reaction to the long-term devastating effects of structural racism on B/I/POC, along with reading, viewing and talking with people like George Aye of Greater Good Studio, to make me realize that the graphic I created in order to articulate an opportunity to address a social injustice could become an obstacle in addressing it. This is true even though the original intent of the diagram was to visualize the relationship between capabilities and cultural competence because it neglected to acknowledge the reasons why cultural competence was necessary in the first place.

This is a classic case of what Robin Diangelo calls being free from the burden of race. In her book White Fragility, she frames the default position of someone like me (white in America) like this: “Another way that my life has been shaped by being white is that my race is held up as the norm for humanity. Whites are ‘just people’—our race is rarely if ever named.” And so issues of race and privilege can be so foreign to people like me that when someone brings them up we’re inclined to think they’re trying too hard to make a point.

Clearly, as designers interested in social impact, there’s a danger of subverting our own efforts in not acknowledging the truth behind the truths. The redesigned graphic (Fig 2) is a more complete depiction of the reality we hope to address. It holds more promise of driving intentional conversations that don’t shy away from the fundamental reality of endemic racial injustice. Without such acknowledgements we will continue to live in a world of corrosive quick fixes and white convenience.

Seeking a Moore’s Law of Social Innovation

We know that if design is to become an effective tool to advance issues of diversity, equity and inclusion, not only are there pillars within our own discipline to be dismantled, but there are foundations from other fields to be more rigorously incorporated. For decades, there has been exceptional design writing urging us to learn from sociology, anthropology, psychology, and other social sciences. But the question of what specifically we should be incorporating from these fields is asked less frequently. We can no longer cherry pick from these disciplines with a default emphasis on expedience. Thankfully, there is a new movement underway in the design world. The guiding principles crafted by the Design Justice Network, as one example, re-center design intention away from superficial and client-driven dictates. And Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) has long provided a working process and philosophy for anyone serious about grass roots efforts of improving the life of people where they live.

While Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous quote that the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice can be comforting, we have to ask how it can be bent more quickly in light of the crises we face today. In 1965, Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, postulated that advancements in computer chips were likely to double approximately every two years, with a commensurate reduction in cost. Such exponential growth—since labeled Moore’s Law—can have its benefits. And it can have its downsides. A good question to ask at this point in history is how might we discover a Moore’s Law of Social Innovation to counter the negative repercussions of our technological infatuations? How do we exponentially grow humankind’s ability to work together at a time when so many global trends are driving personal, social and cultural estrangement? As I’ve written about before, a deeper infusion of the Capabilities Approach into design discourse can be such a catalyst. Just as regenerative farming rebuilds soil in the process of creating food, a regenerative social impact approach that rebuilds human capacity at the individual level in the process of designing transitions to a sustainable economy is needed. If each individual has the capability to enact a future they themselves desire, an exponentially larger percentage of our collective energy would be put toward enhancing our shared future.

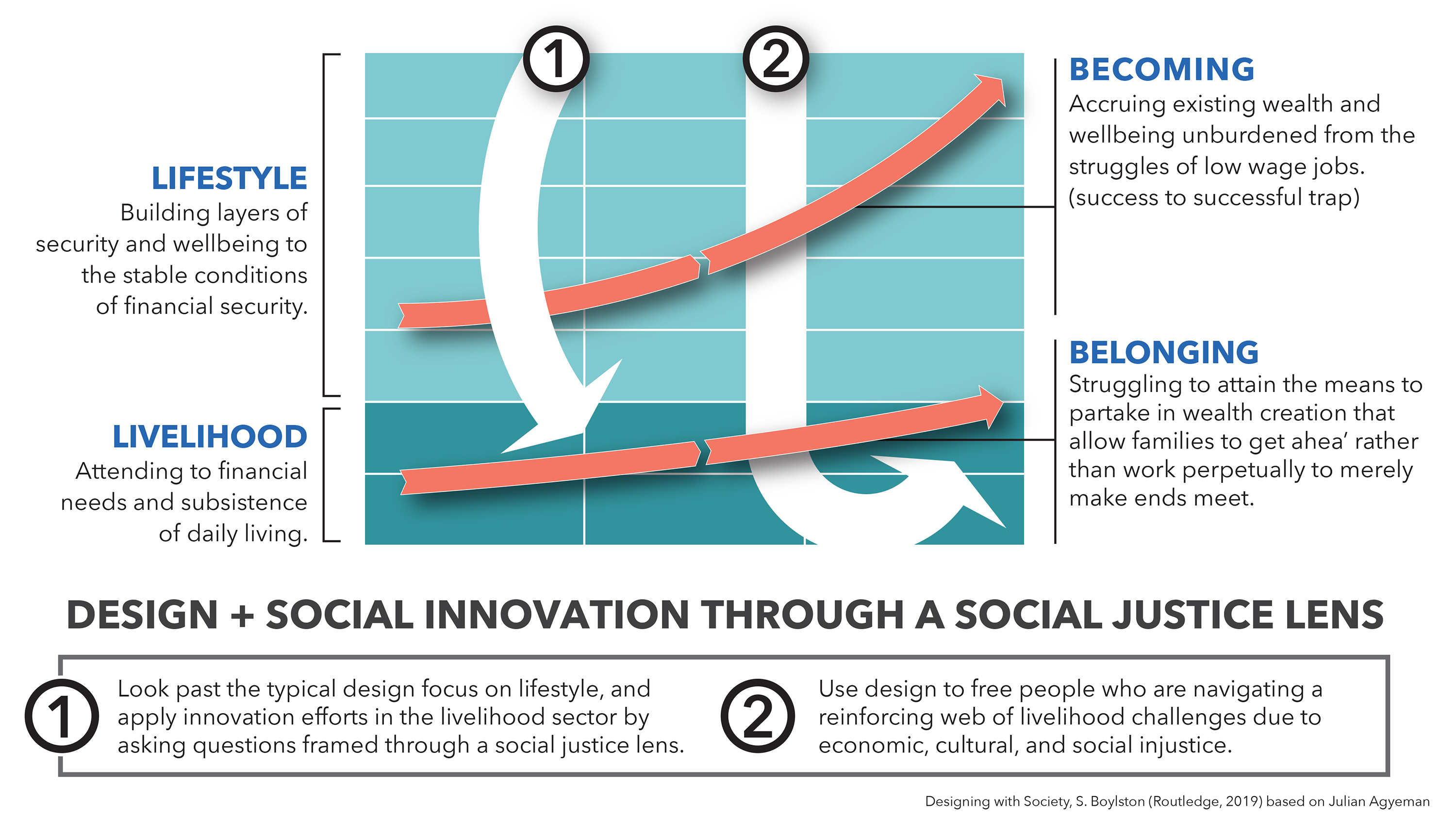

Design for social impact needs to keep asking deeper questions about what social, cultural, and economic factors hold some people back even as they allow others to pass through unmolested. Real solutions lie below a surface we’ve habitually trusted to be the whole of reality. Design’s relationship with helping those who already belong to a world of privilege become more of what they aspire to be is long and storied. Much of that focus has neglected to consider those who still struggle to belong. Through the lens of Just Sustainability, Julian Agyemen has explored this issue of becoming and belonging throughout his career. The graphic above illustrates how a focus on those with privilege—building on their personal becoming by emphasizing lifestyle design—only increases the gap between them and those who have historically been marginalized. Whereas an emphasis on design that enhances the belonging of marginalized groups by securing their ability to establish a rewarding and secure livelihood can narrow that gap. A deeper appreciation for the framing of human capabilities can help designers identify opportunities for meaningful work, and to help drive effective change in those efforts.

When considering the space between what our users hope to achieve in their lives and what they are capable of achieving given their relationship with the world around them, design for social impact must ask harder questions about what kinds of inequality we ourselves perpetuate when we neglect to focus on those who are struggling to belong for the sake of those who have already accomplished (or were born into) that privileged state of belonging.