Military Review, March-April 2010, ad for new Army Field Manual FM5-0

When I get invited by CEOs to talk about integrating design thinking into their organizations, they listen attentively. As they understand what it is, the cautious ones argue that the core of their business is just too important to expose it to the risks of design — and maybe we could experiment with design in some minor part of the business off to the side. My response, typically, is to argue that the core is the most critical place for utilizing design thinking in order to save the core — and their whole business — from the inevitable poor consequences of exploiting the current rather than exploring what might be. But that argument rarely works.

Now I have a better argument to make: if the U.S. Army can do it in the core of its business, so can you! The core of the Army’s business involves not just maintaining market share or enhancing shareholder value but life versus death, freedom versus oppression. Surprising as it may seem at first blush, the U.S. Army has incorporated design thinking into the core of its battle doctrine — and there is something to learn from its efforts.

The series of events that produced this startling result began in 2006, when the U.S. Army began to overhaul a document called “Field Manual 5-0: Army Planning and Orders Production,” or FM5-0 in Army jargon. While it may appear to be a pretty arcane item, like the manual for customer service representatives in a bank, it is anything but. It lays out the core military doctrine that battlefield commanders are taught and expected to use to guide their planning and decision-making.

The overhaul was in response to a battlefield that was becoming ever more complex, unpredictable and dangerous. And as one might expect from the U.S. military, the process took a long time and involved a number of formal revisions — three official drafts, a review and approval in December 2009 by a body called Training and Doctrine Command, and final release of the new doctrine, Field Manual 5-0: The Operations Process, in March 2010.

What might have been less expected is that in the middle of that overhaul process, the concept of design thinking entered the intellectual fray. Design’s arrival on the scene was signalled by a spate of articles in the Army’s key academic journal, Military Review, starting in 2008. It began in the September-October issue with From Tactical Planning to Operational Design by Major Ketti Davison and continued in the January-February 2009 issue with Systemic Operational Design: Learning and Adapting in Complex Missions by Brigadier General Huba Wass de Czege, retired. This was followed by companion pieces authored by Colonel Stefan J. Banach in the March-April issue. The first (co-authored with Alex Ryan) laid out a military interpretation of design: The Art of Design: A Design Methodology. The companion explained how military leaders could be taught design: Educating Leaders: Preparing Leaders for a Complex World. This pair was followed in July-August 2009 with Understanding Innovation by Colonel Thomas M. Williams.

Finally, contemporaneously with the release of the FM5-0, were two articles in the March-April 2010 issue celebrating the new doctrine: Field Manual 5-0: Exercising Command and Control in an Era of Persistent Conflict (Colonel Clinton J. Ancker, retired, and Lieutenant Colonel Michael Flynn, retired) and Unleashing Design: Planning and the Art of Battle Command (Brigadier General Edward C. Cardon and Lieutenant Colonel Steve Leonard).

This all makes for absorbing reading for those interested in design thinking. To me there are three notable points about the Army’s initiative: first, design is now a really big deal in military doctrine; second, the Army has gotten design quite right; and three, the struggle to get design well ensconced in Army doctrine was and remains no easy feat.

Design Is Now a Big Deal

This group of articles first foreshadowed and then celebrated the inclusion of an entire chapter on design in FM5-0. Real estate in this manual is not easy to come by. The core of it, excluding the several introductions and voluminous appendices, is a mere six chapters covering 77 pages. After the overview, there are only five themed chapters — Planning, Design, Preparation, Execution and Assessment — and the third chapter of 13 pages is all about design. Those pages are well worth the read.

This is quite a leap forward from the previous iteration of FM5-0, which didn’t contain a single word about design. And the group of Military Review article writers are unafraid to take pot-shots at the previous military doctrine. In Major Davison’s piece, the prior process is harshly dealt with: “The prevailing planning process, the Military Decision-Making Process, amounts to a mechanistic view of mindless systems... The mechanistic perspective focuses on physical logic and is entirely appropriate — at the tactical level. It becomes incomplete, however, at the more conceptual operational level, where the political objectives of war are at least as important as the physical disposition of forces.” (p. 34)

The Army Has Gotten Design Quite Right

I found the articles referred to above by General de Czege and by Colonel Banach (with Ryan) to be particularly impressive and apt.

De Czege sizes up the challenge as follows: “Nearly all missions in this century will be complex, and the kind of thinking we have called “operational art” is often now required at battalion level. Fundamentally, operational art requires balancing design and planning while remaining open to learning and adapting quickly to change.” (p. 2) To him, the ubiquity of complexity necessitates a different form of thinking — including abductive logic — in the following way: “Where merely complicated systems require mostly deduction and analysis (formal logic of breaking into parts), complexity requires inductive and abductive reasoning for diagnostics and synthesis (the informal logic of making new wholes of parts),” which in turn “implies a new intellectual culture that balances design and planning while evincing an appreciation for the dynamic flow of human factors and a bias toward perpetual learning and adapting.” (p. 3)

Banach’s thinking clearly played a seminal role in the development of the new Army doctrine. He thoughtfully contrasts science with design in the following way: “Design is focused on solving problems, and as such requires intervention, not just understanding. Whereas scientists describe how the world is, designers suggest how it might be. It follows that design is a central activity for the military profession whenever it allocates resources to solve problems, which is to say design is always a core component of operations.” (p.105) It is very interesting to see an organization so defined by science and technology see the limitations of purely scientific thinking.

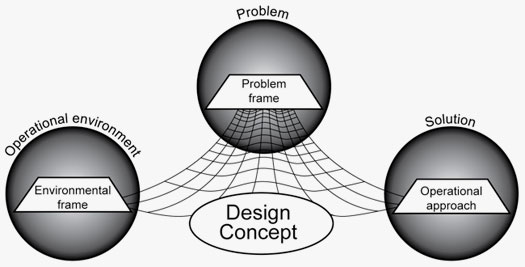

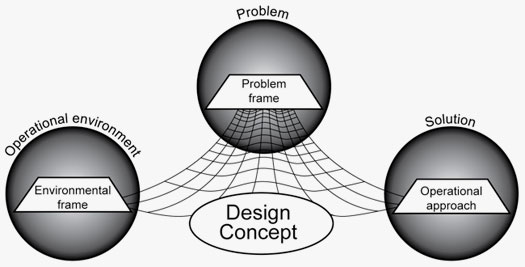

Banach’s other contribution is a conceptual model for design in the military and on the battlefield with an approach to linking the overall environment, the problem at hand, and the potential solution. The model is found both in his own paper (p. 144) and in the final FM5.0 (p. 3-7). While it may not be the most elegant graphic, the model itself embodies the degree to which design is an iterative process in which the thinking must go back and forth between elements of the situation at hand and the possible solutions to come up with what the military calls a “design concept.”

Banach and Ryan, "The Art of Design: A Design Methodology," graphic, The Three Design Spaces

In the end, FM5-0 defines design as “a methodology for applying critical and creative thinking to understand, visualize, and describe complex, ill-structured problems and develop approaches to solve them” (Page 3.1), which is a pretty good definition of design. Ancker and Flynn go on to argue that design “underpins the exercise of battle command within the operations process, guiding the iterative and often cyclic application of understanding, visualizing, and describing” and that it should be “practiced continuously throughout the operations process.” (p. 15-16)

It Was and Continues to Be a Struggle

While the design component of the resulting doctrine was pretty impressive, it was evidently somewhat of a struggle to bring the artistry of design to the machinery of the U.S. Army. After reading the articles and the final document, I came to see the design transformation tasks that I have taken on pale in comparison. When Claudia Kotchka, Procter & Gamble’s first vice president of design strategy and innovation, asked me in 2005 to help her solve the problem of integrating the design work she and colleagues were doing with IDEO and other design firms into the strategy process at P&G, I thought it was a tough challenge. We had to find a way to make the fuzzy front end of design connect seamlessly to the analytics of strategy. It was not easy, but the task seems like child’s play in comparison to the U.S. Army’s figuring out a way to hard-wire design thinking into its exceedingly detailed and rigorous doctrines and processes for Planning and Execution.

Even its proponents, like de Czege, are philosophical about the difficulty of the sale in tradition-bound military: “Those who believe the military has no business in ambiguous missions and complex settings are its most ardent opponents. Then there are those who prefer the traditional approach to complexity: overwhelm and obliterate it.” (p. 12) In the midst of the fray in mid-2009, Williams entered with a stern admonition to not get carried away with the innovation of design: “The problem is, in contemporary usage, the word innovation is now just a buzzword used to sell everything from software to blenders. Its definition is now so broad that we can declare nearly every unorthodox action, thought, or event acceptable as long as we label it innovative. Whether conducting counterinsurgency operations, preparing for conventional war, or transforming to meet new and yet undefined threats, imprecision begets failures. Regulations and field manuals arrayed in lines of vague language will only serve to confuse leaders and produce well-intentioned but misguided actions.” (p. 59)

In early 2010, with FM5-0 fully approved, the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS) began teaching the new design doctrine. In order to promote discussion and understanding of design, SAMS created a blog for classmates to discuss design, and it makes for very interesting reading.

Major Ed Twaddell leads off with: “Design has encountered resistance throughout its introduction into Army doctrine and the Army lexicon. In order to improve the Army’s design approach and smooth its doctrinal introduction, the Army must standardize the language of Design; define the doctrinal relationship between Design and the operational art; and clarify at what level of war Design is suitable for use.” Major John Ebbighausen remains unconvinced: “Design methodologies and planning processes produce similar products...design authors have not demonstrated the non-doctrinal methodologies differ from the doctrinal planning process.”

Major Randall Wenner finds the notion of a design concept confusing: “During our most recent design practicum, it became clear that a cognitive gap exists in understanding how to translate the design concept (DC) into a campaign design concept (CDC). Additionally, there is confusion in understanding the difference between a design concept and the campaign plan concept. Is the campaign plan concept a PowerPoint brief that is not as detailed as the campaign plan itself, and what is the difference between the campaign design concept versus the campaign plan concept? Are these two concepts different? Generally, it is understood that once a design concept is developed and approved it serves as a basis for the commander to publish his guidance for the campaign design. There is no clear guidance as to what constitutes the campaign design concept.” And bless him, J.D. Williams desperately wants a checklist: “The greatest difficulty with the Army’s current design approach and methodologies is that there does not appear to be a checklist, or a step action drill, for military designers to follow in the practice of design. The nonlinearity of the cognitive spaces in design is intellectually stimulating, but it leads to confusion as critical terms lack definitive clarity and authoritative sources have been vague on the procedural steps.”

Conclusion

The U.S. Army has been creative, open and brave to adopt design thinking into its doctrine. But as is the case with most organizations that recognize that their world has gotten so complex that their traditional thinking modes are no longer up to the task and turn to design, the Army will have a struggle to push aside the traditions of analytical thinking to leave space for design thinking. But unlike many organizations, the Army has made a very bold start with the overhaul of FM5-0 and its embrace of design thinking.

Now I have a better argument to make: if the U.S. Army can do it in the core of its business, so can you! The core of the Army’s business involves not just maintaining market share or enhancing shareholder value but life versus death, freedom versus oppression. Surprising as it may seem at first blush, the U.S. Army has incorporated design thinking into the core of its battle doctrine — and there is something to learn from its efforts.

The series of events that produced this startling result began in 2006, when the U.S. Army began to overhaul a document called “Field Manual 5-0: Army Planning and Orders Production,” or FM5-0 in Army jargon. While it may appear to be a pretty arcane item, like the manual for customer service representatives in a bank, it is anything but. It lays out the core military doctrine that battlefield commanders are taught and expected to use to guide their planning and decision-making.

The overhaul was in response to a battlefield that was becoming ever more complex, unpredictable and dangerous. And as one might expect from the U.S. military, the process took a long time and involved a number of formal revisions — three official drafts, a review and approval in December 2009 by a body called Training and Doctrine Command, and final release of the new doctrine, Field Manual 5-0: The Operations Process, in March 2010.

What might have been less expected is that in the middle of that overhaul process, the concept of design thinking entered the intellectual fray. Design’s arrival on the scene was signalled by a spate of articles in the Army’s key academic journal, Military Review, starting in 2008. It began in the September-October issue with From Tactical Planning to Operational Design by Major Ketti Davison and continued in the January-February 2009 issue with Systemic Operational Design: Learning and Adapting in Complex Missions by Brigadier General Huba Wass de Czege, retired. This was followed by companion pieces authored by Colonel Stefan J. Banach in the March-April issue. The first (co-authored with Alex Ryan) laid out a military interpretation of design: The Art of Design: A Design Methodology. The companion explained how military leaders could be taught design: Educating Leaders: Preparing Leaders for a Complex World. This pair was followed in July-August 2009 with Understanding Innovation by Colonel Thomas M. Williams.

Finally, contemporaneously with the release of the FM5-0, were two articles in the March-April 2010 issue celebrating the new doctrine: Field Manual 5-0: Exercising Command and Control in an Era of Persistent Conflict (Colonel Clinton J. Ancker, retired, and Lieutenant Colonel Michael Flynn, retired) and Unleashing Design: Planning and the Art of Battle Command (Brigadier General Edward C. Cardon and Lieutenant Colonel Steve Leonard).

This all makes for absorbing reading for those interested in design thinking. To me there are three notable points about the Army’s initiative: first, design is now a really big deal in military doctrine; second, the Army has gotten design quite right; and three, the struggle to get design well ensconced in Army doctrine was and remains no easy feat.

Design Is Now a Big Deal

This group of articles first foreshadowed and then celebrated the inclusion of an entire chapter on design in FM5-0. Real estate in this manual is not easy to come by. The core of it, excluding the several introductions and voluminous appendices, is a mere six chapters covering 77 pages. After the overview, there are only five themed chapters — Planning, Design, Preparation, Execution and Assessment — and the third chapter of 13 pages is all about design. Those pages are well worth the read.

This is quite a leap forward from the previous iteration of FM5-0, which didn’t contain a single word about design. And the group of Military Review article writers are unafraid to take pot-shots at the previous military doctrine. In Major Davison’s piece, the prior process is harshly dealt with: “The prevailing planning process, the Military Decision-Making Process, amounts to a mechanistic view of mindless systems... The mechanistic perspective focuses on physical logic and is entirely appropriate — at the tactical level. It becomes incomplete, however, at the more conceptual operational level, where the political objectives of war are at least as important as the physical disposition of forces.” (p. 34)

The Army Has Gotten Design Quite Right

I found the articles referred to above by General de Czege and by Colonel Banach (with Ryan) to be particularly impressive and apt.

De Czege sizes up the challenge as follows: “Nearly all missions in this century will be complex, and the kind of thinking we have called “operational art” is often now required at battalion level. Fundamentally, operational art requires balancing design and planning while remaining open to learning and adapting quickly to change.” (p. 2) To him, the ubiquity of complexity necessitates a different form of thinking — including abductive logic — in the following way: “Where merely complicated systems require mostly deduction and analysis (formal logic of breaking into parts), complexity requires inductive and abductive reasoning for diagnostics and synthesis (the informal logic of making new wholes of parts),” which in turn “implies a new intellectual culture that balances design and planning while evincing an appreciation for the dynamic flow of human factors and a bias toward perpetual learning and adapting.” (p. 3)

Banach’s thinking clearly played a seminal role in the development of the new Army doctrine. He thoughtfully contrasts science with design in the following way: “Design is focused on solving problems, and as such requires intervention, not just understanding. Whereas scientists describe how the world is, designers suggest how it might be. It follows that design is a central activity for the military profession whenever it allocates resources to solve problems, which is to say design is always a core component of operations.” (p.105) It is very interesting to see an organization so defined by science and technology see the limitations of purely scientific thinking.

Banach’s other contribution is a conceptual model for design in the military and on the battlefield with an approach to linking the overall environment, the problem at hand, and the potential solution. The model is found both in his own paper (p. 144) and in the final FM5.0 (p. 3-7). While it may not be the most elegant graphic, the model itself embodies the degree to which design is an iterative process in which the thinking must go back and forth between elements of the situation at hand and the possible solutions to come up with what the military calls a “design concept.”

Banach and Ryan, "The Art of Design: A Design Methodology," graphic, The Three Design Spaces

In the end, FM5-0 defines design as “a methodology for applying critical and creative thinking to understand, visualize, and describe complex, ill-structured problems and develop approaches to solve them” (Page 3.1), which is a pretty good definition of design. Ancker and Flynn go on to argue that design “underpins the exercise of battle command within the operations process, guiding the iterative and often cyclic application of understanding, visualizing, and describing” and that it should be “practiced continuously throughout the operations process.” (p. 15-16)

It Was and Continues to Be a Struggle

While the design component of the resulting doctrine was pretty impressive, it was evidently somewhat of a struggle to bring the artistry of design to the machinery of the U.S. Army. After reading the articles and the final document, I came to see the design transformation tasks that I have taken on pale in comparison. When Claudia Kotchka, Procter & Gamble’s first vice president of design strategy and innovation, asked me in 2005 to help her solve the problem of integrating the design work she and colleagues were doing with IDEO and other design firms into the strategy process at P&G, I thought it was a tough challenge. We had to find a way to make the fuzzy front end of design connect seamlessly to the analytics of strategy. It was not easy, but the task seems like child’s play in comparison to the U.S. Army’s figuring out a way to hard-wire design thinking into its exceedingly detailed and rigorous doctrines and processes for Planning and Execution.

Even its proponents, like de Czege, are philosophical about the difficulty of the sale in tradition-bound military: “Those who believe the military has no business in ambiguous missions and complex settings are its most ardent opponents. Then there are those who prefer the traditional approach to complexity: overwhelm and obliterate it.” (p. 12) In the midst of the fray in mid-2009, Williams entered with a stern admonition to not get carried away with the innovation of design: “The problem is, in contemporary usage, the word innovation is now just a buzzword used to sell everything from software to blenders. Its definition is now so broad that we can declare nearly every unorthodox action, thought, or event acceptable as long as we label it innovative. Whether conducting counterinsurgency operations, preparing for conventional war, or transforming to meet new and yet undefined threats, imprecision begets failures. Regulations and field manuals arrayed in lines of vague language will only serve to confuse leaders and produce well-intentioned but misguided actions.” (p. 59)

In early 2010, with FM5-0 fully approved, the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS) began teaching the new design doctrine. In order to promote discussion and understanding of design, SAMS created a blog for classmates to discuss design, and it makes for very interesting reading.

Major Ed Twaddell leads off with: “Design has encountered resistance throughout its introduction into Army doctrine and the Army lexicon. In order to improve the Army’s design approach and smooth its doctrinal introduction, the Army must standardize the language of Design; define the doctrinal relationship between Design and the operational art; and clarify at what level of war Design is suitable for use.” Major John Ebbighausen remains unconvinced: “Design methodologies and planning processes produce similar products...design authors have not demonstrated the non-doctrinal methodologies differ from the doctrinal planning process.”

Major Randall Wenner finds the notion of a design concept confusing: “During our most recent design practicum, it became clear that a cognitive gap exists in understanding how to translate the design concept (DC) into a campaign design concept (CDC). Additionally, there is confusion in understanding the difference between a design concept and the campaign plan concept. Is the campaign plan concept a PowerPoint brief that is not as detailed as the campaign plan itself, and what is the difference between the campaign design concept versus the campaign plan concept? Are these two concepts different? Generally, it is understood that once a design concept is developed and approved it serves as a basis for the commander to publish his guidance for the campaign design. There is no clear guidance as to what constitutes the campaign design concept.” And bless him, J.D. Williams desperately wants a checklist: “The greatest difficulty with the Army’s current design approach and methodologies is that there does not appear to be a checklist, or a step action drill, for military designers to follow in the practice of design. The nonlinearity of the cognitive spaces in design is intellectually stimulating, but it leads to confusion as critical terms lack definitive clarity and authoritative sources have been vague on the procedural steps.”

Conclusion

The U.S. Army has been creative, open and brave to adopt design thinking into its doctrine. But as is the case with most organizations that recognize that their world has gotten so complex that their traditional thinking modes are no longer up to the task and turn to design, the Army will have a struggle to push aside the traditions of analytical thinking to leave space for design thinking. But unlike many organizations, the Army has made a very bold start with the overhaul of FM5-0 and its embrace of design thinking.