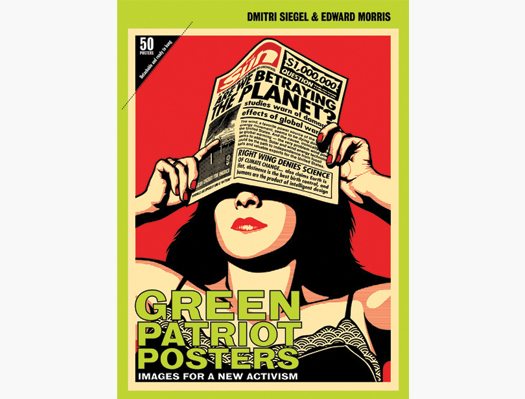

Cover of Green Patriot Posters: Images for a New Activism, edited by Edward Morris, Dmitri Siegel. Text by Michael Bierut, Thomas L. Friedman, Steven Heller, Edward Morris, Dmitri Siegel, Morgan Clendaniel. Published by Metropolis Books

Most People just don't get climate change. Few grasp the need and more important, the opportunity to transform our society. So the people who do get it need to be louder, more insistent and more effective at getting the message across.

This is predominantly a framing problem and a framing problem is, in essence, a marketing problem. With the Green Patriot Posters project we looked to the graphic design and artistic communities for ways to invigorate and mobilize people to remake our economy for a more sustainable future. We wanted to contribute something to the rebranding of contemporary environmentalism, bringing climate change and the drive for clean energy to center stage and minimizing fear mongering about eco-apocalypse and mushy anthropomorphism of “mother earth” with their hand-me-down aesthetics and naive obsessions.

With this in mind we set out to collect and commission posters that created a stronger, more urgent and more relevant movement. Like most people looking to build something from scratch, we started with our friends and branched out from there.

Where Is the Third Wave?

This year we celebrated the fortieth anniversary of Earth Day in the United States, but of course the environmental movement in this country is much older than that.

In a 1986 Wall Street Journal editorial, Fred Krupp of the Environmental Defense Fund broke down the history of the movement into three “waves.” The first wave, he wrote, “was a reaction to truly rapacious exploitation of natural resources in the wake of the Industrial Revolution” and the focus then “was on conservation, stemming the loss of forest lands and wildlife, especially in the West.” The second wave “recognized that the contamination of water, land, and air had sown seeds of destruction for both wildlife and humans. The strategy in this second phase has been to try to halt abusive pollution.”

The first two waves had great success. First wave: the creation of our National Forests, the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964; second wave: the passage of the Clean Air Act, the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Our air and water are cleaner and more land is protected. Our very consciousness about the environment has changed. We have become more sensitive to ecology.

Yet Krupp was right to point out that the environmental movement needed a new direction, a third wave and that the old paradigms starkly opposing industry and nature were worn out and counterproductive. An emphasis on conservation and purity made the movement seem precious and out of touch. Not far off were the cries concerning “the end of nature” and “the death of environmentalism” (both titles of books that would be published in the years to come).

The problem is that twenty years later the focus has been found, but the strategy has not. Climate change is clearly the challenge of our times, but is the environmental movement doing a good job of motivating the public to address it? In our view, despite its successful history and the urgency of its current agenda, the environmental movement has not evolved to meet the challenge of this third wave. It is broad but weak — weaker than it should be given the imperative of its message.

It is a movement that primarily seems to concern affluent people in mostly superficial ways. Younger people, who are the real stakeholders given that they will inherit an environment on the verge of collapse, are weirdly apathetic, hedonistic and cynical. Less affluent people, who are the most likely to feel the impacts of climate change — crashing economies and pollution — can’t find enough head-space for these concerns in a world overcrowded with anxieties. Conservatives have become convinced that this once nonpartisan issue is now a threat to their core values. America’s future is at stake and precious few seem to really care or even understand.

Why Graphic Design?

So why graphic design? What can it do? The inspiration came first from WPA (Works Progress Administration) and World War II posters. During the war, the United States was able to mobilize industry and its citizens with breathtaking speed. Factories were overhauled and consumption habits were transformed. Conservation (in the form of rationing) became a patriotic act. Strong, graphically compelling posters played a crucial role in the success of this campaign. In these posters, taking action was presented as vital for the good of the nation, and those who were willing to sacrifice were portrayed as dynamic American heroes. This is just what we need today.

Contrast the power and effectiveness of these World War II images with some of the current visual media in the environmental advocacy realm. In the latter, there are essentially three modes: 1) Save the earth (which to us seems meaningless and apparently strikes the general public as crying wolf). 2) Save the animals (not meaningless at all, but dodges the crux of the matter: future human suffering vs. continued human prosperity). 3) Eco-apocalypse (a legitimate possibility, but a trope that often feels whiny and too distant to be actionable). All of these strategies also suffer from the fact that by the time their truth is tangible to the public it will be far, far too late.

So what is right for our time? We took the approach that no one person knows the answer, and that is why we opened up the project to multiple designers and to the general public. But the posters we selected for this book represent a particular vision — the vision of the editors. We believe that graphic design does not just respond to the zeitgeist, it helps shape it. With that in mind we generally sought posters that convey urgency and/or optimism (in a word: strength), but we kept an open mind about the specific content or imagery we received.

What We Got

As posters started rolling in some inspired us, some depressed us, and some just confused us. But several topics recurred, including bicycles, local food and renewable energy/the end of oil. Notably each of these is positive, solution-oriented, visualizable, and realizable, and each gives distinct agency to the individual.

The bicycle is a nonthreatening, non-ideological image, un-sanctimonious and almost childlike. At the same time its mere presence is a direct challenge to our car culture, which drives so much CO2 into our atmosphere. It is also a symbol of individual responsibility and empowerment in the face of an overwhelming challenge. As we mentioned above, the individual is the most meaningful institution in our culture today, so it is probably no coincidence that the bicycle — a vehicle built for one — would be so resonant.

Posters about local food were among the most fun and the most inclined to employ retro-imagery — a reminder that the values of this movement have deep roots in American society.

Alternative technologies were valorized in many of the posters, including Fairey’s iconic windmill. These images reflect a faith that technology and innovation are the great assets of America that will surmount the challenge of climate change — an interesting update to the qualities of determination, grit and resourcefulness, which were the focus of the World War II–era posters. These works clearly represent a yearning for a different kind of industry, one that harnesses technology, capital and innovation in the interest of more than just shareholder value — actual values. There is clearly an opportunity for energy companies to replace reckless, shameless practices like deep-water drilling with clean-energy exploration.

Not surprisingly many designers, particularly many of the youngest designers, deftly adapted the humor and irony that dominate our culture to the cause, hijacking this vernacular for a higher purpose. Jeremy Dean’s co-opted rap lyric in It’s Getting Hot in Here, Xander Pollock’s melting of Al Gore’s face and Jude Senese’s playful exhortation to add the earth as a friend all proved that a contemporary environmental movement needs to speak in a contemporary language. Several designers, perhaps frustrated with the lack of credible institutions, made up fictitious ones — Eric Benson’s Renewable Electrification Administration, DJ Spooky’s People’s Republic of Antarctica.

Yet what struck us most was the polyphonic nature of the submissions. There is no one prevailing ethos, aesthetic, or message. We see this as a strength, not a weakness. It is a sign of the times and of what is needed to invigorate the environmental movement to address the challenges of climate change and energy independence: flexibility, dynamism and the embrace of complexity and multiplicity.

The above text by Edward Morris and Dmitri Siegel, is from the introduction of Green Patriot Posters (Metropolis Books, 2010) and has been reprinted here with the author's permission.