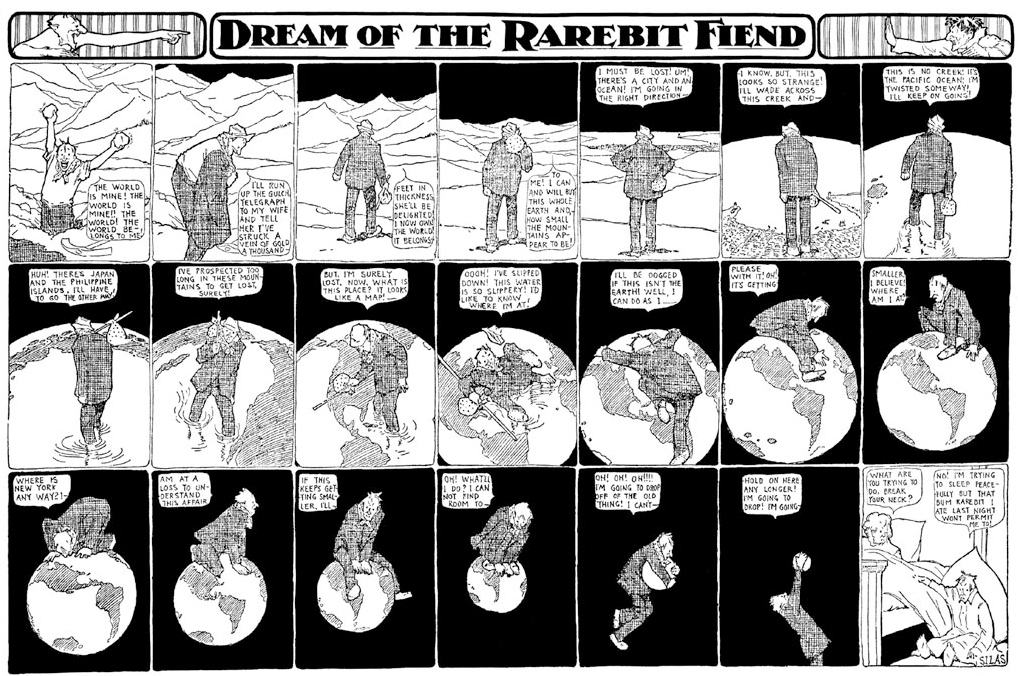

Winsor McKay, Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, September 21, 1907.

Dreaming is how we allow the unconscious mind to improvise. Protagonists shift, context blurs, and stories unfold in warped time. Objects in dreams loom with symbolic resonance that sometimes hits you over the head. (Other times, maddeningly, the symbolism eludes you completely.) In a dream, you play all the parts: you’re the director and the cinematographer, the judge and the jury. You’ve written the script, designed the costumes, and cast yourself as every character.

Dreams have a poetic integrity, Emerson wrote, a truth.

And therein lies their haunting beauty. You can’t will yourself to dream, but you might, at a minimum, think about how the mind might stretch a bit, even relax a little. The reward—counterintuitive as it may seem—is that you’re granted access to something else, proximity to some deeper part of yourself, perhaps. And what if giving permission to that kind of imaginative access were something you could do in your waking hours?

From 1904 to 1925, a tabloid cartoon called Dream of the Rarebit Fiend was published two to three times a week in the New York Evening Telegram. The brainchild of the prolific American illustrator Winsor McKay (of Little Nemo fame) the strip itself followed a simple format: each frame showed someone in an improbable situation—being swallowed by a multi-limbed monster, for example, or dancing with a skyscraper stretched like taffy—simply because that same someone had eaten a Welsh Rarebit (essentially a grilled cheese sandwich) before bed.

Stay with me, here.

What’s so extraordinary about McKay’s work is his early nod to surrealism—the idea that irrational juxtapositions of images could cue, and be cued by the unconscious mind—ideas that would later find expression in the work of André Breton, André Masson, Max Ernst and others. (Bear in mind that the surrealist movement didn’t begin in earnest until after World War I: McKay was way ahead of his time, here.)

The series brilliantly visualized the dream state by riffing on the fleeting beauty of perceptual disturbance. A hat brim stretched to the size of a football field. A sidewalk peeled back to spiral into infinity. Floating beds in starless, ebony skies, and bodies pulverized into fragments of dust, only to be reconstituted an instant later as other objects. McKay masterfully interwove them all, always finding a way to resolve the narrative in fewer than a dozen frames.

That dreams connect us to ourselves in a deeper way is not always a source of creative ignition. As a sleep-challenged young mother, I dreamed rather incessantly about laundry (hardly a model of divine inspiration) except that in hindsight, it was, in its way, mildly McKay-esque: colorful stacks of childrens’ clothes towering up high, growing faster than I could handle. Just as my children were.

Emerson may not have been a surrealist, but he understood surrealism’s implicit grammar. The mind, he wrote, once stretched by a new idea, never returns to its original dimensions.

In a cultural moment that is increasingly being referred to as, yes, surreal, a little imaginative surrender isn’t a terrible idea, here.

To relax the protocols of the conscious mind, to let go of the rules that govern your methodical practice? Imagine the possibilities. Indulge the fantasies. Maybe ditch the laundry. (And the cheese.) Let this be your moment to improvise—radically, deliriously, even irrationally. Enjoy the ride.

And dream big.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.