On the fiftieth anniversary of the Selectric typewriter (eulogized so well on these pages by Phil Patton and Julie Lasky) I was reminded not only of my first Selectric memory (green, my father's oak-panelled office on Long Island, circa 1975), but of the heavy nostalgia for it wrought one summer day on the banks of the Mississippi when on a roadtrip, I stopped in the Quad Cities for lunch, and came across a typewriter repair shop in Davenport, Iowa (or was it Moline, Illinois?). The shop was packed with beautiful and obsolete machines of all vintages, but it was the mint condition taupe Selectric for $35 that found it's way to the trunk of my car for the long drive back home.

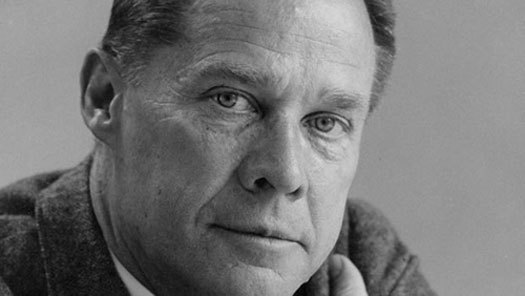

The Selectric's designer, Eliot Noyes, could hardly be described as a one-hit wonder, but still he remains oddly under the radar of all but the most devout design afficionados. He was a gifted architect (who trained under Gropius and Breuer), was appointed director of the department of industrial design at MoMA (at 30), was a professor at Yale, directed Norman Bel Geddes's office, and established the corporate design programs for IBM, Westinghouse, and Mobil Oil — some of the most recognizable corporate marks in design history — spearheading the new culture of critical design conciousness in the business world.

He also wrote fairly widely on design. When, in 1947, Consumer Reports enlisted Noyes to write a column called “The Shape of Things,” the eleven-year-old magazine had already cemented its image as a defender of the consumer's right to know everything about the products they might be deliberating over — from material quality to manufacturer integrity to safety. The son of a Harvard English professor, Ralph Caplan called Noyes “the most literate designer I knew.” His first column, however, which appeared in the April 1947 issue, was not a thing of beauty. Somewhat perfunctory, it covered Fisher & Scott radios and “food mixers.” His criticism, though seemingly well-deserved, pulls no punches and isn't exactly subtle. Over time, his writing not only settled, it ranged into discussions of manufacturing, do-it-yourself, and generally embraced and nurtured a culture of readers who were not as well versed in design as today's target audience for Eames chairs and Vitsoe shelving.

Postwar America was on a home-building spree, and American families, many with newly returned GIs and newer houses, were on a shopping bender: white goods, furniture, radio sets, even long playing records, were meticulously tackled by the watchdog publication. What was not often a consideration in the manifestly fact-driven pages of Consumer Reports was the question of a product's aesthetic qualities. Museums like MoMA in New York and academic institutions (University of Illinois) were examining exuberant new designs and unpacking the consumer's desire for postwar renewal. The country was just warming to the “art of modern living,” shaking off the fusty mantel of the interwar period. Enter Noyes and his reputation as a designer, teacher, and architect of intelligence, dignity, and taste. He was adamant that attractive design pieces were not paradoxical, and his Consumer Reports set out to educate the reader and steer both the afficanado and the novice toward good value by emplying a sophisticated critique of the era's changing design landscape.

In Gordon Bruce's mammoth illustrated biography of Noyes (2006), he wrote that Noyes believed that “good design should ensure that compatibility reverberates among all its separate parts … .” During his tenure as the director of MoMA's industrial design department, he championed the idea that good looks were equal to a designer's responsibility to good performance, value, and ease of use. “The consumer,” he wrote in his July 1949 column, “has a real interest in well-designed objects, for the qualities that the good designer seeks to achieve are largely the qualities that best serve the user.” This could just as well describe his method in engaging the reader-consumer in the CR pieces. They've read the price and size comparisons of various washing machines and irons, but have no idea what their design entails, or how the new modern designs might fit into their dometic milieu. In his January 1950 column on the uptick in museum exhibits of useful objects (like those popular at MoMA and the Walker Art Center), he sounds determined to make the public aware that “the design of saucepans is interesting and important,” and encourages museums to take amore active role in the lives of their constituents. He, of course, was the curator and developer of many such exhibitions, but he wasn't a typical proselytizer for new design. “It is important to analyze what is available in terms of your needs,” he wrote in September 1947. While a champion of clean-lined modern living, he recognized the significance of heirlooms and family pieces having a place in one's home. Not deterred by the limitations some items, even those reviewed by his employer, he not only proposed that old and modern pieces could live happily together, but he was not above giving advice on DIY projects, and devoted a whole column to them in November 1947 (entitled “You Can't Put These Under the Christmas Tree, but … .”

For Noyes, the column, coupled with the efforts museums were making to open up new design to public scrutiny was a crucial step in paving the way for recognition not just of new design, but important new processes that were changing manufacturing in the country after the war. He often couched his ideas and critiques in a more holistic, cultural approach. For example, the nature of and advances in manufacturing were often under discussion. Though mass production was entering the manufacturing conciousness, the promise of quality, mass produced furnishings was a ways off (it still seems that way today), and often what was considered “mass” was still too expensive for most households: factories weren't yet equipped with the latest technology, and while gaining popularity, modern furniture wasn't yet mainstream enough for manufacturers to keep costs down. In a 1950 column on a museum design prize for modern chairs, he highlighted an advertisement from a NYC department store that proudly announced: “We sell chairs that look like chairs!” complete with a picture of the prize winning Pratt chair (“looks like a maladjusted banana”), Knorr chair (“like a flying saucer”), and the Eames shell rocker (like an“amphibious cauliflower ear”).

If he wasn't above taking a good-natured ribbing, he wasn't above giving one, either. A proponent not just of the successful merging of practicality and good design, the purist in Noyes rankled at what he viewed as the constant “misuse and misunderstanding of form.” One of Noyes' biggest pet peeves was the unnecessary embellishments that commercial designers added to their objects. In multiple columns, including his very first, “streamlining” became a subject of villification, and probably constitutes the most exasperated he ever sounds. He wrote, “The tendency to streamline static objects has been one of the most annoying and least justifiable design mannerisms of the past decade.” “... [T]here is often an indication of an ability to move at high speed. The Sunbeam [food mixer] … has some little horizontal lines or 'speed whiskers' on its sides. They are intended to be decorative, but are dirt catchers.” A year later he devoted an entire column to this design injustice with regard to clothes irons, one of which he described as having such a “swept back” look so as possibly to break the sound barrier. A couple of years later, the “dubious” aesthetic enhancement of this practice took center stage in a column about postwar car design: the “design nonsense” and “pure corn,” for example, of garish decorative chrome and his biggest bugbear, chrome painted to resemble wood.

There was also some prescience. In March 1949, he devoted a column to the forerunner of prefab flat-pack furniture, which was then called Knock-down (or KD) furniture, appropriately. Much like IKEA today, this is what Noyes had to say about the KD trend: “Anyone with a little experience can assemble the pieces, but it isn't as easy as it sounds.” “The furniture looks better in the photographs than in actuality.”

“For what you get it should cost less; or, for what you pay, it should look better in the end.” The aching familiarity of these lines — admit it, we've all thought the very same ourselves — and his quietly intelligent approach to his own designs and his critique of design culture justifies this year's noisy tributes to his superseded, but hardly obsolete, Selectric. Eliot Noyes' under-recognized reputation deserves the same kind of appreciation.