Four months before his Radio City Music Hall mural makes its grand debut, Ezra Winter marries for the second time. The bride, a divorcée two years his junior, is Mrs. Edna Albert (née Murphey), daughter of a Cleveland surgeon who made a name for herself at a young age by inventing and marketing an antiperspirant for women. Having sold her business three years earlier, she is at once financially solvent and unencumbered by obligations. And she’s looking for her next challenge.

She is an unlikely thing for a woman at that time: a serial entrepreneur.

In the coming years, she will both add to and retreat from that characterization, building a new company and hiding behind the illusion of domesticity that her new rural livelihood affords her. Writing about the second Mrs. Winter some years later, a New York Times reporter will struggle with precisely this paradox: "If all this makes you think of a glittering, pushing, career woman, hell-bent for success, you’re wrong. Patricia Winter is very pretty, very feminine, very gentle, and a little shy. "

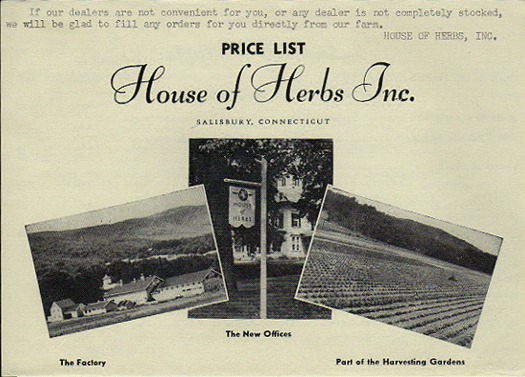

They are married at the South Canaan meetinghouse in Falls Village, Connecticut. Edna, who goes by the name “Pat,” retains her elegant apartment at One East End Avenue, and together, in the year that follows — it is now 1933, arguably the worst year of the Depression — the newlyweds will purchase a limited edition Marmon convertible and some hundreds of acres in the Berkshires on which they will build a new studio for Ezra.

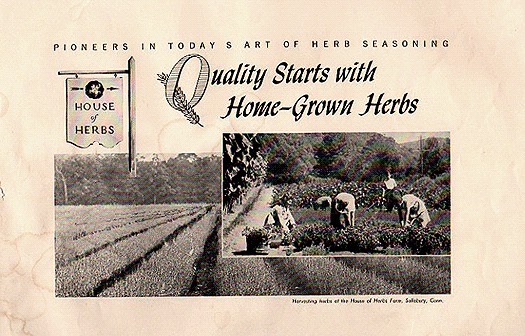

They call their estate Juniper Hill, sitting as it does on a massive parcel of land covered in multiple variations of low-growing conifers. In Latin, the word juniperus combines junio (which means young) with parere (a verb meaning “to produce”). And how perfect a setting this is for the painter, who has now concluded the painting about — but not necessarily his own quest for — the Fountain of Youth. And for his ambitious Bride, who will transform this property into a working farm where she will grow acres upon acres of fresh herbs.

At one point, Pat Winter has nearly 35,000 basil plants growing in the meadow.

Pat Winter photographed in her garden in an undated photo

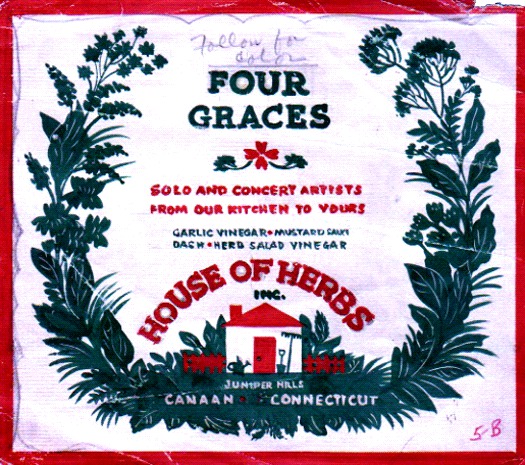

Pat Winter photographed in her garden in an undated photoShe begins slowly selling them to local farmers. Later, she has a chicken coop built, and is soon breeding livestock which she grows and sells at substantial profit to New York City restaurants, over three hours away by train. Over time, she finds uses for the herbs — flavored vinegars, for instance — and publishes small recipe books as premiums. Juniper Hill becomes House of Herbs.

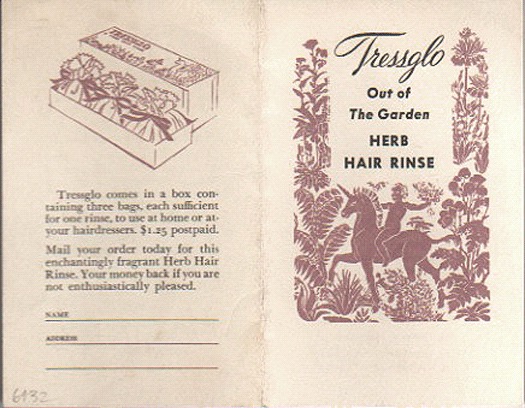

Nodding to her earlier incarnation as a cosmetics guru, she even makes and markets her own brand of cream rinse, which she dubbs Tressglo.

Ezra Winter, famed mural artist, designs the identity for her products as well as many of the actual labels.

A muralist married to an herbalist. What are the odds?

For his part, Ezra is hard at work producing seven 28-foot murals for the George Rogers Clark Memorial in Vincennes, Indiana. Photographs of him during this period begin to reveal a visible strain. His face is drawn. He looks weary and detached. As ever, his correspondence is overrun with financial worries, and on more than one occasion he writes to request larger advances from his clients. For every late alimony payment, there is a vindictive letter from Vera. Pat, who adores the Winter girls (who are now teenagers) only intervenes when the children are involved.

Jeanette and Renata Winter

And then, in April, 1933, Ezra Winter is invited by the critic Eugene Klute to deliver a fifteen-minute radio talk on the subject of mural painting in relation to modern life, to air live over the Columbia Broadcasting System. In it, the artist tries desperately to convince himself that he has embraced the modern world. The talk is scripted and stilted, carefully worded but difficult to parse. His words, though direct and impassioned, betray an awkward uncertainty.

“When I say that the mural painter is, first of all, a decorator, I mean that he is more interested in beautiful, thrilling color combinations, the shapes and sizes of forms, and in patterns and their complementary relation to each other, than he is in the realistic depiction of an event, an object, or a place.”

Was he really so incapable of summoning the powers of the imagination in relation to the visual depiction of an idea? Several years earlier, in his notes on the painting of the Eastman Murals, Winter had written of his own perceived parallels between music and nature. In his view, frogs were bagpipes and seashells were trumpets: could the composition of a painting follow a similarly metaphorical, if not entirely musical shape, he wondered? And yet, such gestural whimsy could take him only so far: accomplished as he was as a technician and imbued as he may have been with an interest in beautiful and thrilling color combinations, Ezra Winter’s paintings were anything but modern.

To his radio audience, he suggests the opposite:

“I feel that we should all be optimistic about the modern art movement. Many people resent the effort to change our artistic ideas and methods and are offended by much that is called modern art. I think that they are justified when the expression is ugly, crude, grotesque or primitive. We are not primitive savages. At least, not most of the time.”

Did Ezra Winter believe that modernism somehow imperiled the civilized society into which he had been granted access? Did he think that the grotesque could be defined by him — or, for that matter, by anyone? And as he spoke of primitive savages, might he subconsciously have been thinking of his friend Eugene Savage — colleague at the Yale School of Art who would soon succeed him on the Commission of Fine Arts? There is throughout this address something distinctly false — in the formality of the language, in the artist’s public admonitions — as though he is trying to brainwash himself as he evangelizes his public. Is it an act of wishful hubris? In his own mind, even the artist himself believed, on some very essential level, that this was a pantomime. In a letter to a friend, he would later write, “Recently, I have had to become something of an actor to do my work.”

An actor he may have been, but a struggling one, for no matter how vociferous his protestations, no matter how indelibly he hoped to link modernism to mural painting, his own work remained profoundly tethered to the notions of decoration that were no longer held in such esteem by the newly modern world. And so, the same year that Henri Matisse creates The Dance II tryptych for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, the same year that Diego Rivera paints the Detroit Industry murals, Winter, steeped in his own arguably antiquated canon, writes the following to Charles Moore, then-Chairman of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts:

I am absolutely in favor of the four rows of elms rather than the one row of elms and mixed planting behind. This may be difficult to accomplish but I am certain that the effect would be very fine and beautiful.

Perhaps in his studio up on Juniper Hill, buffered by his wife’s herbal empire, “very fine and beautiful” was all that mattered. “Very fine and beautiful” — this was language from another world, the patois of the decorator, the embellisher, the picture maker who could not abide the possibility that something might be “ugly, crude, grotesque or primitive” — neither in his work nor in his studio, in his vast garden, in his elegant cars or on his massive canvasses. To be modern was to accept the dislocation of form, the slippage between ideas, and the possibility that everything was not always going to be very fine and beautiful. To Ezra Winter, that was simply not possible.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

Some footage courtesy of Northeast Historic Film/Albert Conley CollectionExcerpt from Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copland, performed live by the Sydney Camerata Chamber Orchestra