Made from prefabricated parts, the Float House will cost about $150,000

In repopulating cities hit by Hurricane Katrina’s floods, or anywhere waters rise (as they do increasingly around the world), the big question racking the brains of architects and planners has been how to keep houses high and dry when storms surge onshore. The common impulse has been to find ways to hike up the main living areas of houses to 10, 15 or 20 feet high, which is rather imposing on a dry day and costly when you consider that elevators run easily into the five digits.

But today, architects at Morphosis in Los Angeles, working with graduate architecture students at the University of California, Los Angeles, unveiled another solution: a floating house. In the Netherlands, as Morphosis principal Thom Mayne points out, the notion is not novel, yet it hasn’t really been tried in this country. Rather than design around the idea of a house as a fixture on the ground, the Morphosis/UCLA team came up with a house that can close up tight and rise like a boat does in a marina at high tide — and do so affordably.

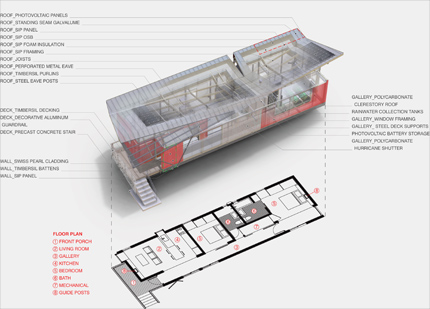

Float House components. In the event of flooding, the structure rises on two steel guideposts (8).

The Float House, on Tennessee Street in the flood-ravaged Lower Ninth Ward, will cost about $150,000; the architects gleaned savings from prefabrication and mass production. It was designed over the past two years for Make It Right, a foundation started by the actor Brad Pitt to help rebuild New Orleans with sustainable, storm-resistant housing.

This model is not a far cry from Louisiana shotgun house. It’s a long box, sided in fiber-cement panels with a folding, photovoltaic roof. Inside, rooms range along one wall and open onto a gallery running the house’s length. Beneath the house is a modular chassis of polystyrene foam blocks encased by glass-fiber-reinforced concrete. Inside the chassis are the house’s guts — plumbing and electrical and mechanical equipment, plus rainwater collection tanks and battery packs charged by the sun. (The house is equipped to go off the grid.)

Concealed inside either end of the structure is a 12-foot-high steel guidepost, anchored by pilings driven down 45 feet. If water were to rise around the house, it would float straight upward along the guideposts and stay fastened to the site. Indeed, at first the house was too light and needed ballast. “It had too much buoyancy,” Mayne says, “so we added a topping slab to the mass of the building, like putting a lead keel on a boat.”

There were a number of code issues to work out with the local building cops, given its nonstandard systems and structure, but it eventually won their approval. Apparently, no insurance underwriter has weighed in on the design yet, but, Mayne says, “I would think they’d be elated,” because during a flood, the homeowner’s biggest investment should stay intact. Ideally, by that time, the homeowner will have closed the carbon-fiber panels over the windows and left town.

Tom Darden, executive director of Make It Right, says the house is going on the market almost immediately. “I would expect that thing to sell in 30 days or less,” he says. It will likely go to a family already enrolled in the foundation’s homebuyer counseling process.

Mayne says that whoever lives there will hardly notice the guideposts or the floatation apparatus. “I see it as a safety belt or an air bag in a car,” he says. “It doesn’t get used. And then when you need it, it gets used.”