Editor's Note: Kathryn Lofton's “Forms of Attention” is the introduction to 55x5, a book of photographs by Alan Thomas, just published by Marquand Editions.

How do we define the line between attention and obsession? I want my lover’s attention. I want the attention of a reading public. I want the attention of students not just toward me, but also toward each other, toward the texts and objects that define our classroom work. I am a reasonable person (she tells herself). I just need a little attention.

I talk with a teenager and she observes of a particular friend’s boyfriend that “he is obsessed with her.” She says this with barely smothered hunger. The desire for someone’s attention is inevitably more: the desire for someone to be distracted by you. A glance isn’t enough. You want a stare. Attention is a gentleman’s word, a word for a focused pause amid the regular proceedings. Obsession is when the proceedings get re-routed. When fascination becomes preoccupation, urge becomes fixation, craving becomes fetish.

The photographs in this book appear at a historical moment in which photographic obsessiveness is one of the more legitimate public manias. Not just legitimate, but a social norm. If you were born after 1990, you enter the world through self-illustration: through your production of self on a variety of apps and websites that allow users to share pictures. Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Flickr, Snapchat. Image messaging is to the twenty-first century what the letter was to the eighteenth: this is how we come to know ourselves and be known.

Like every form of communication ever conjured by human hands, these mobile applications quickly find their idiomatic cliché. Individuality is the purpose of the whole venture (see me, as myself, in this specific world I forge), but the peculiar is overridden by the connective competition of the familiar. Which is just another way to say that in a world of 600 million active Instagram users, there are not 600 million different ideas about what to photograph or how.

Ask college students what kind of photos are most familiar to them, and they’ll list recurring genres like a scholar. First, of course, there are the selfies: duck face selfies, bathroom mirror selfies, bikini in the bathroom selfies, evening wear selfies, eye selfies, bum selfies, selfies in bed, selfies first thing in the morning, selfies last thing at night, selfies-of-self-taking-selfies. In selfie, I become.

Beyond the self-portrait, though, there are the objects, and the objectifying of the self: photos of your fresh nail art, of latte art, of artfully presented meals, close-ups of unhealthy food, long looks at healthy food. The viewer is asked to look at shots of your wake-up time, your SMS correspondence, your playlist, your inspirational quotation. Among the most popular repeat images on Instagram, the only pictures that don’t involve your person or taste are pauses for sky-oriented wonderment: tall buildings shot from the ground; airplane wings; cloudy skies; sunsets. Indeed, the obsessive repetition of sunrise or sunset pictures on photo-sharing sites has led to the colloquial diagnosis of a mania: solsnapomania.

The photographs of Alan Thomas cannot be understood without acknowledging the quiet critique that they mount of an Instagram universe. At the time of its 2010 launch, a distinctive feature of Instagram was that it confined photos to a square shape, similar to Kodak Instamatic and Polaroid SX-70 images, in contrast to the 4:3 aspect ratio typically produced by mobile device cameras. Five years later, Instagram would adjust its framing, allowing users to upload media captured in any aspect ratio. The original Instagram shape is the one Thomas relies upon most here, using the Polaroid frame—imposed by an in-phone app--as the graphical access point for his stare.

His use of the square makes the image seem at once a snapshot and a specimen. Thomas is catching something while on his way to something else. He is also collecting variations as if for science. It is this meta-consciousness that contains the rebuke. The maker of a Polaroid wants to grab a minute and make it special. Thomas wants to show how our special is perhaps all a matter of design.

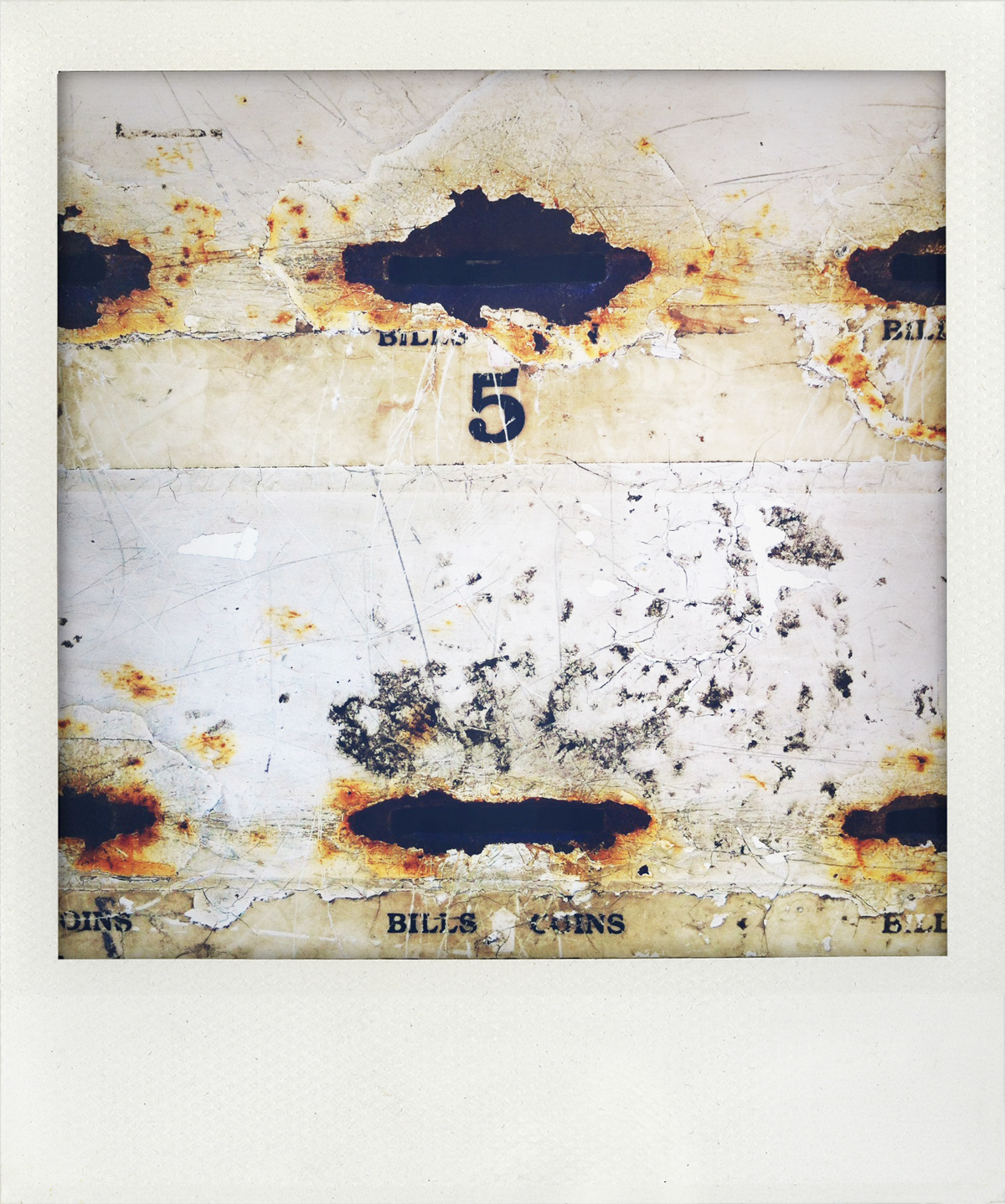

There are six extraocular muscles that control the movements of the eye, and when you look at Thomas’s photographs, those muscles go to work. Stop for a minute and see how each photograph makes you search it. The subject seem at first apparent, but it isn’t. Every slice is an optical illusion of a kind; you think it’s a number you’re here to see, but it isn’t always quick to find. Or if it is, you can’t quite grab the context: is that a painted sign or a printed billboard, a detail on a door or a window? Is it a miniature of a regular thing or a regular thing made to look miniature? Science generates knowledge by attempting to eliminate potential sources of bias, often through controlled experiments. The photographer here seems to pose a question through his disciplined frames about the nature of the thing he is repeatedly seeing. What is this?

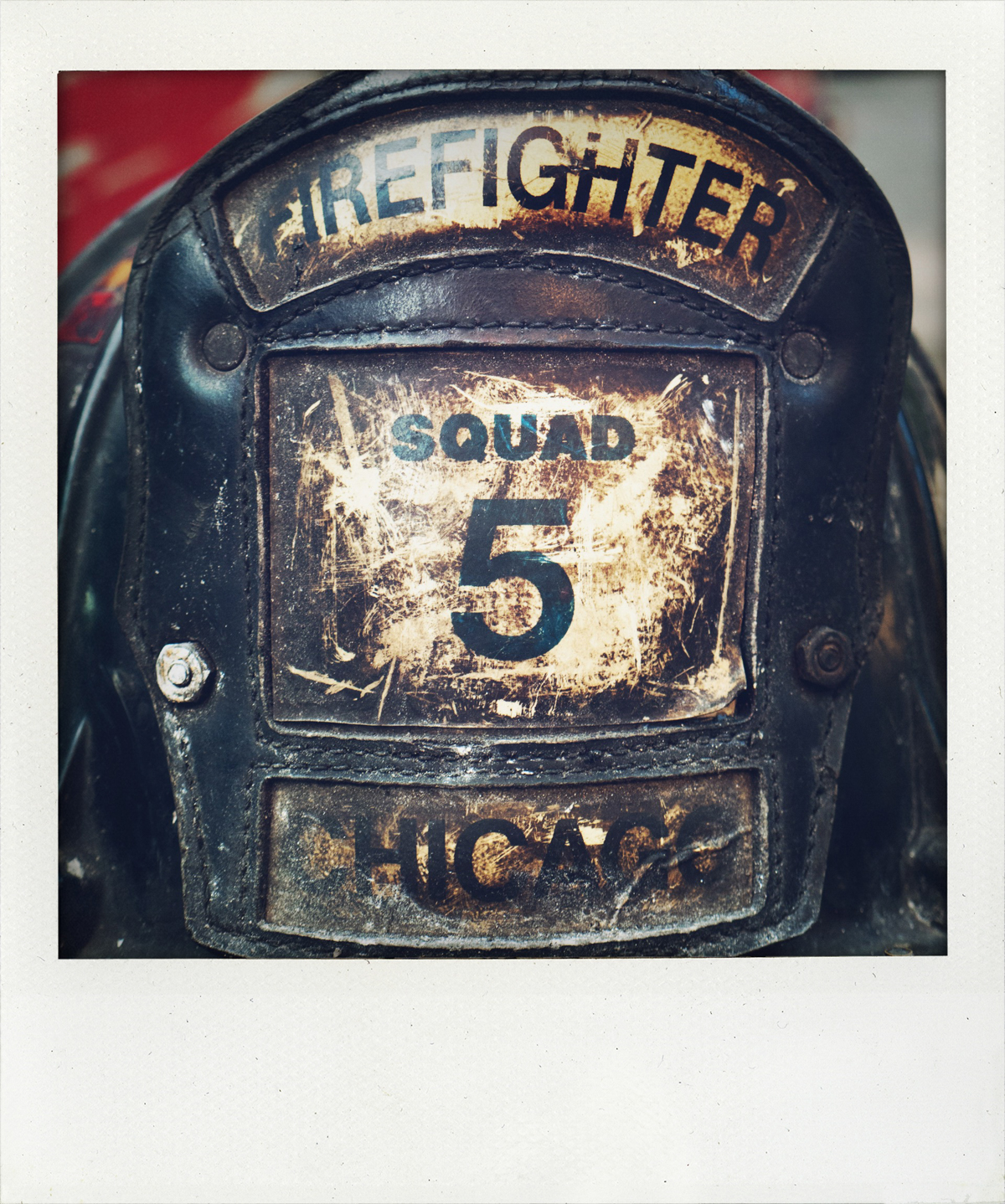

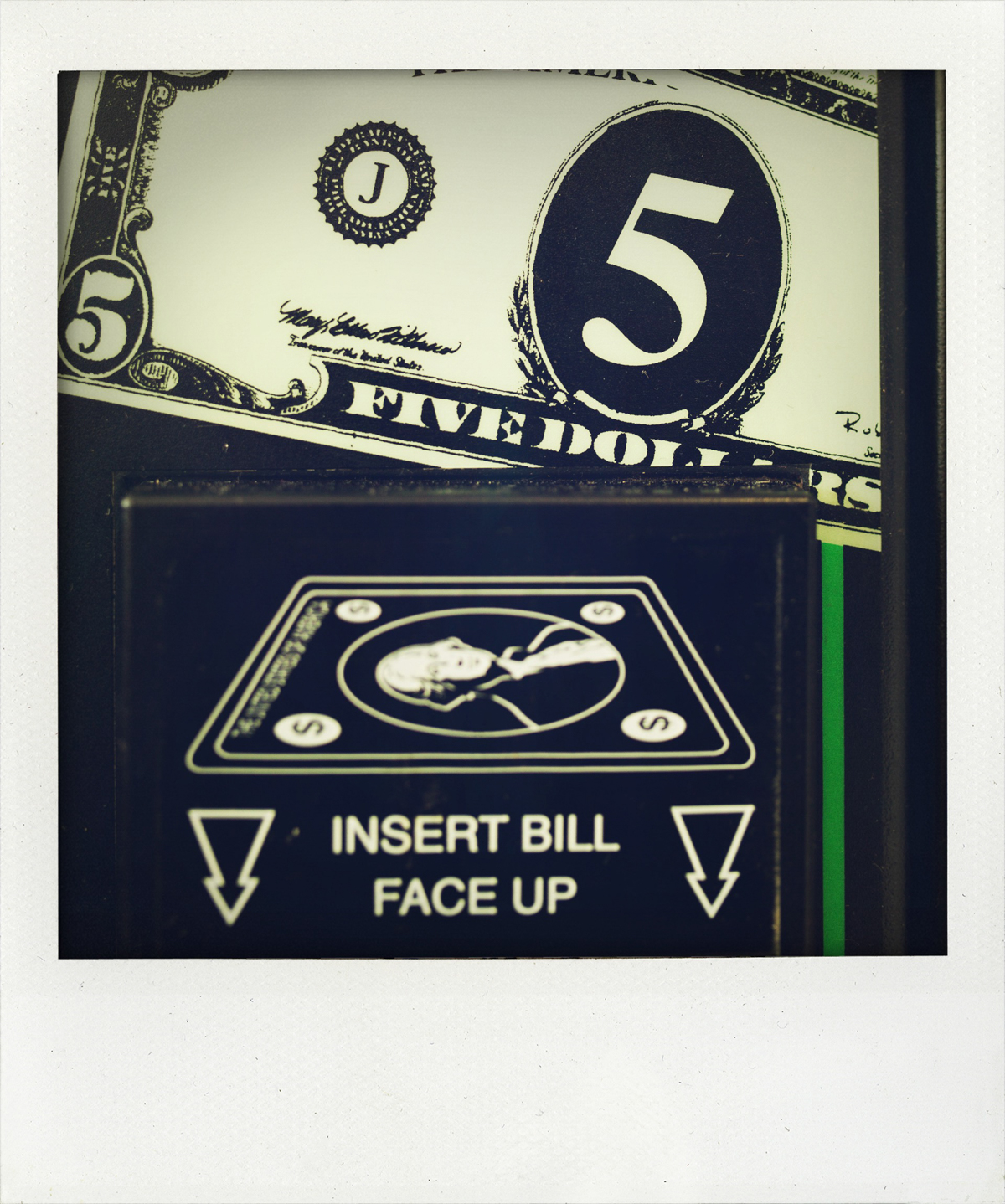

Inside the squares are shards of the glancing day: signs, addresses, labels; vestibules, alleyways, hallways; insignia, graffiti, instructions. There is a sense that you’re in common noun places: train stations, airports, fire stations, mason lodges, parking lots, banquet halls, public schools. You can’t tell, quite, but you can figure it out. The human body is there—the person with the T-shirt or the tattoo—but it doesn’t quite register. The artist is clear: he doesn’t want the bias of the body. He doesn’t want you to think about humans as the precious site of individuality expressed but instead to discern our common landscapes as the place into which we insert ourselves. Where we become numbers.

The photographer asks you to recall that detail you are annoyed to forget: Where did you park? Where does she live? Which one is this? How many was that? Rather than glance at the pieces squared here, the camera stares. Pulls in. And finds one thing, over and over and over: 5.

The repetition of such a specific figure of attention can at first suggest obsession. Psychologists understand mania as an exceptional state relative to everyday experience. We are, in a given life, aroused or affected or energized. Mania is an abnormal elevation of those senses. Labeling mania abnormal suggests it is a disorder—that feeling that good isn’t very good for us. Or maybe it isn’t right for us? There are manias triggered by specific objects: anthomania (flowers), bibliomania (books), hippomania (horses), or pteridomania (ferns). People who love Liszt could have Lisztomania. People who love Harry Potter could have Pottermania. The question of where this abnormality is a worrisome disorder or a praiseworthy uniqueness really depends on whether you think such obsession is better than attention.

The photographs are trying to teach us about this. They are trying to make us think about what it means when seeing itself is commodified, when platforms are designed to circulate our sights. In such a world, these quietly stunning images stand out for their unabashed excitement for the plainest of all possible things. A single-digit number.

Any number you pick you could perhaps argue into interpretive excess. Two, three, four—all of them have social and philosophical inferences galore. Scholars of religion, however, know that five has a weird intrigue. Like comedians with their rule of threes, religions have rules of five. Many traditions of practical medicine and astrological interpretation focus on the differing potency of the five elements (water, fire, earth, wood, and metal); in Sikhism there are five virtues (truth, compassion, contentment, humility, and love) and five vices (lust, rage, greed, attachment, and ego). Jesus supposedly received five piercing wounds during the crucifixion. The Torah has five books (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) and Islam has five pillars (the testimony of faith, ritual prayer, the paying of alms, fasting on Ramadan, and the pilgrimage to Mecca). Abu Bakr, the first to assume the title of caliph, succeeded to the leadership of the early Muslim polity after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. He wrote, “He who prays five times a day is in the protection of God, and he who is protected by God cannot be harmed by anyone.” Why five? Because when the angel Gabriel appeared to Muhammad he led him in prayer five times. And so it was practiced, and so it was done.

Is five the number of certain authority because it is the number of fingers I have on my hand? Is it because almost all mammals (and our ancestors, those amphibians and reptiles) have five fingers or toes on each extremity? Is five magic because it’s the one we have on us, always? Or is five such a phenomenal figure to behold because it has a figurative quality itself—the sharp top, the rounded bottom. The five is a head with a cap on it. It’s a human leaning over a wheel.

One of Thomas’s photographs has a skinny white five overlaid by a murky scrim of deep teal and grayish white. The bluish-greenish part of the background looks like a T. Or it looks like a form under water, the shape of something in cloudy liquid trying to press against the glass wall so it can be seen. So it can get out.

In the fifth circle of Dante’s Inferno, the passively wrathful sinners lie beneath the water. Crime novelist and sometime classicist Dorothy L. Sayers wrote in her commentary on this part of that epic poem: “the sullen hatreds lie gurgling, unable even to express themselves for the rage that chokes them.”

One of the photographs shows a stenciled white five painted on something metal that was painted blue. You know it is painted metal because in the middle of the five there is a bit of peeling paint, and a rusty streak underneath it. It looks like someone was shot.

5 (Murder by Numbers) was a mix tape released by American rapper 50 Cent in 2012. It was supposed to be the full-length follow-up to 2009’s Before I Self-Destruct, but was at the last minute relegated to a ten-track shorter cut. The chorus of “Business Mind” sticks hard: “I got a business mind—that block is mine / That brick and them Glocks is mine.”

One of the photographs has a sans serif five with a thick arrow on its right pointing southeast. To be more precise: it’s pointing to five o’clock. It looks to be directing us to a lower floor. Is it background to a scene in a movie where the character needs to run down stairs to escape whoever is following her. Is this the story where she makes it, or where she dies on three?

Every security password I have uses the number five. Every wager I make includes the number five. If I meet you and five is in your birthday it is possible we may get serious fast. Five is not my lucky number. It is my geomagnetic pole. One of the photographs shows an arm that looks like a mobile crane with the boom latticed by a Demuth five. That arm is mine.

We have five senses. We can try to divide them, to close our eyes and savor a bite, to link hands in the dark. We can take a photograph, and look at it: a distillation of our visual attention. But the other senses rise up—jealous, maybe, at all that attention—and contaminate any effort at purity. When we taste something, we smell it in our noses and we feel it on our tongue. In the end, five is indivisible.

Manias can seem to blanch the selected object of its arousal into a thing more handled than felt. But these photographs avoid that fate. Their gathering is a spur to feeling, not its attenuation. If you let yourself, you can fall into the crevices they expose. With their focus and discipline, their order and humor, their methodical clarity and adventitious appearance, these photographs ask you to think about why your eye catches on some things and not others. Why you attend to that one thing, but never noticed something else.

These photographs don’t ask you to pay attention. They suggest, instead, that it’s time to get obsessed. Go out, go. Find your 5.