But food and drink? The branding, the packaging, the communications, the stores, the promotions, the trade shows, the hotels, the restaurants? Would I be wrong to guess that 75% of us have worked for a global food enterprise, directly or indirectly, at some point? I know I have: an industry talk here, a futures workshop there, a couple of healthcare events…

But two new publications this week have left me sick to the stomach. I just don't think it's defensible any more to turn a blind eye to the social and ecological crimes Big Food is committing, in other parts of the world, so that you and I can eat what we damn well feel like.

When it comes to the food business, I've been having my cake, and eating it, since 1995. That was when Vandana Shiva spoke at Doors of Perception 3 about the hidden but devastating ecological and social costs of global industrial agriculture. That was a wake-up call.

Food figured prominently in 2000, too, when we did Doors East in Ahmedabad We learned, then, that for eighty million women in India, who own or look after one or two cows, milk is their only livelihood.

It should not have been a surprise last week, then, to read a grim report entitled “The great milk robbery: How corporations are stealing livelihoods and a vital source of nutrition from the poor.”

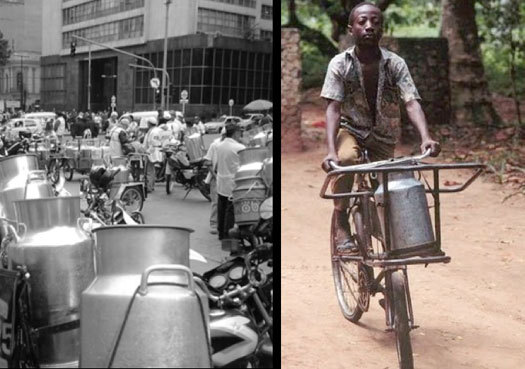

Left: Colombia's jarreadores (Photo: Aurelio Suárez Montoya). Right: mobile milk delivery in Kenya

In a long and scrupulously documented report, an NGO called Grain confirms the importance of so-called “people's milk” to the livelihoods and health of hundreds of millions of poor people in the global South — from small-scale farmers and pastoralists, to local cheesemakers and fresh milk vendors. They nearly all supply safe, nutritious and affordable milk at a mainly local scale.

The report chronicles in distressing detail the global push by Big Dairy corporations such as Nestlé, PepsiCo and Cargill to colonise this entire milk flow. Instead of fresh, high-quality milk produced and supplied in the most sustainable ways by small scale farmers, Big Dairy's strategy is to replace their local milk with powdered and processed milk, produce it on highly polluting mega farms, sell it in excessive packaging, display it in wildly over-chilled stores and, after all that, charge at least double the cost of “peoples milk.”

A continued shift to large-scale farms would be an environmental and public health catastrophe. Big Dairy's farms guzzle enormous quantities of water, often at the expense of local communities that depend on the same sources. Their mega-farms also require a lot of land — not just for their cows to live on, but to produce their feed.

They also produce massive amounts of waste. An industrial farm with 2,000 cows produces as much waste as a small city.

We know the Big Dairy push is an existential threat to the South because it already happened in the North. The US lost 88 percent of its dairy farms between 1970 and 2006, while the original nine countries of the EU lost 70 percent between 1975 and 1995. Since then, land-grabs and market manipulation have accelerated — accompanied, along the way, by profoundly misguided programmes to impose a high-cost, high-tech “green revolution” on Africa's farmers.

Instead of new hybrid seeds, chemical fertilisers and pesticides, family farmers in West Africa said they want to use local seeds, avoid spending precious cash on chemicals and most importantly to direct public agricultural research to meet their needs.

Where agriculture was born — and is now dying

My sense of quease was further exacerbated last week by reading Food, Farming, and Freedom: Sowing the Arab Spring by Rami Zurayk.

Zurayk, a senior Lebanese agronomist, was not surprised by the Arab Spring. He's been charting the collapse of traditional agricultural livelihoods in the Middle East since the late 1980s — latterly in his blog Land and People. That project grew out of a mobile agricultural clinic designed to help small producers rebuild the livlihoods that their enemy's assaults had shattered.

Zurayk explains that although the Arab Spring may well have been enabled in part by social media, its roots go much deeper.

The middle east is where agriculture first emerged, 10,000 years ago. The most important crops and animal species originated there. Yet today, middle eastern countries are the world's largest importers of food. More than 50 percent of the calories eaten in Lebanon are imported. In Iraq it's worse. In the 1950s, Iraq was self-sufficient in agricultural production, by 2002 she relied on imports for 80-100 percent of many staples.

What went wrong? Can things be fixed?

At one level, when Zurayk explains the between food and farming and the geopolitics of the region, prospects there look grim. Local food production is perceived by enemies of the small farmers to be a form of opposition to their military-territorial objectives. This explains the systematic bulldozing of olive trees, some of them hundreds of years old, in the West Bank and Gaza.

Neo-liberal economic policies have also had catastrophic impacts. Large scale export-oriented agriculture — promoted by global corporations, banks, and many development agencies as the 'road to growth' — has been a boon to local elites. In Lebanon today fifty percent of the farmland is owned by just 3.5 percent of the farmers — usually absentee landlords.

This export-scale agriculture involves the systematic abuse of agrochemicals. Industrial-scale monocultures have caused tremendous damage to biodiversity and to the fertility of the soil itself.

Industrial agriculture is also a major cause of social dislocation. Poor rural people are first displaced from their land; they then do marginalized work in contract farming; when that becomes unsurvivable, they are driven out of farming altogether into the 'misery belts' that surround most cities. There, as patterns of production and consumption have changed, obesity and malnutrition have become widespread among the poorer social classes — the majority of the Arab people..

The pattern is repeated in other African ex-colonies, too, such as Egypt and Kenya — wherever, in fact, a country is 'opened up' to 'modernisation and development'.

India steps back

As in the middle east, so too in India, farming and food retail are about more than trade. They are the very stuff of culture and ecology, of food security, of identity and of livelihood.

In 2007, we focused the whole of Doors 9, in Delhi, on food systems.We were told, then, that 29 percent of school-age children in Delhi are classified as obese, that the sugar content of their diet has risen 40 percent during the last 50 years, that its fat content had risen by 20 percent.

Powerful forces were already pushing India to speed up this industrialisation of food and the corporatisation of retail. The informal sector did not sell branded products — so big business did not like them, we were told. The construction lobby and landowners could not tolerate vendors' occupation of commercially viable urban space, for which they pay no rent. Delhi's municipal authorities wanted food sales off the streets as part of a “clean-up” ahead of the Commonwealth Games.

Large multinational retailers like Wal-Mart, TESCO, Carrefour, and Metro have been trying to expand into India for years — sometimes in partnership, always as teachers, with local business houses such as Reliance, the Tatas, Reliance Industries, Aditya Birla. The grand strategy is to offer cheaper food to price-conscious middle-class Indians.

Last week, India suspended plans to “open” its $450 billion supermarket sector to foreign firms such as Wal-Mart. The Financial Times complained that this retail “liberalization… would have improved the functioning of its supply chain". Prior to its suspension, the Economist had praised law for "opening up its underdeveloped and fragmented retail market". A Tesco spokesman said the move was a "missed opportunity for customers".

The language used by the the business press and the management consultants is soporific and reassuring: “Liberalization” “Opening up” “Opportunity.”

The realities that these words hide are evil, pure and simple.

State-of-the-art sustainability

These words are also profoundly old-fashioned.

With 12 million outlets, India has the largest density of small shops in the world. Her so-called “unorganized” retail sector, with its infrastructure of bazaars, mandis and haats, has evolved over centuries into an ecology of 40 million traders, shopkeepers, hawkers and vendors, together with 650 million farmers.

This amazing ecology is labour-intensive, low entropy, low-cost, decentralized, self-organizing, highly efficient — in a word: resilient.

In sustainability terms, India's legacy farming, food and retail systems are state-of-the-art. And it's this ecology that “organized retail” wants to sweep away.

The corporate take-over of retail is often justified in terms of efficiency. Corporate boosters argue that 40 per cent of horticulture produce in India is wasted. In the informal sector, the opposite is the case: fruit and vegetables that go bad are eaten by cows, or are composted. This recycling of organic matter is only possible in a highly decentralized system. The global giants are the real wasters. Globalised retail is responsible for the waste of 50 percent of food — not the small farmers and retailers.

Another argument is that farmers will get better prices in a more “efficient” system. Yeah, sure. Nowhere in the world is there evidence that corporations like Walmart and Tesco have increased returns to indigenous subsistence farmers. Their entire business model is based on industrialising production, buying at extremely low prices, and undercutting small retailers and street vendors.

Says Vandana Shiva: "the Walmart model is a model for genocide. A retail monopoly, by buying below the cost of production, and by robbing them of other markets through destroying other alternatives, will destroy farmers". In the past decade, 200,000 farmers have committed suicide in India. For Shiva, this is a direct result of agricultural modernization, including the introduction of genetically modified crops.

Superfoods

A couple of months back I heard a woman from Pepsico talk about her company's big push into “superfoods”. Pepsico will work every angle hard to persuade people to pay premiums of at least 25% on their 'super' eats. This has got to mean a *heap* of new work for designers.

But, after reading this week's reports, I've got to say something: for me, given what I know now, working for these guys would be like supping with the devil. During the past years of step-by-step incremental change, of being reasonable, of being grown-up, the situation on the ground — for millions of vulnerable people, and untold vulnerable ecosystems — has gotten steadily worse.

What, you will fairly ask, are you supposed to do with this statement? I don't know. It's a dilemma, not a problem to be solved.