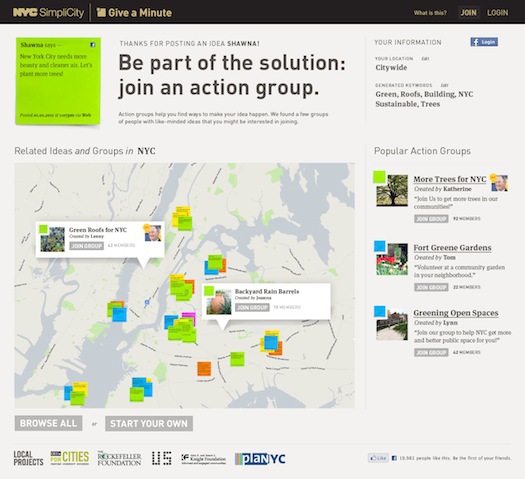

Give a Minute homepage features a user interface modeled on Post-it notes. Courtesy Local Projects.

One needn’t be a Walden-clutching Luddite to be wary of social media’s creep into the political process. Even in the roiling urban soup championed by Jane Jacobs, what increasingly passes for public discourse is a hashtag-strewn Twitter thread. To remind city dwellers of their vital roles within both their neighborhoods and cities, a new initiative doesn’t propose turning back the clock so much as recalibrating its movement.

“It doesn’t take a ton of insight to recognize that the existing public participation process does not really work well,” says Jake Barton, founder of Local Projects. His New York–based interactive design firm was recently charged by CEOs for Cities, an urban think tank, with what Barton demurely calls an “open” brief: to reimagine the public process for the 21st century.

His team responded with Give a Minute, a project that encourages urban citizens to organize and act to improve their blocks, stoops, playgrounds, even exercise routines, thereby drawing the attention — and financial support, where appropriate — of city officials. The model will be given its most thorough test to date in New York beginning this spring.

“In our current participation process, the powers that be plop down a plan in front of you,” Barton says. “That system is hardwired to invite conflict.” To resolve that tension and concentrate citizens’ efforts, Give a Minute would engage people through compelling public messages, and then set them using organizational and fundraising tools such as Kickstarter.com to set their own agendas.

In a pilot program last year, ads in Chicago’s El cars asked passengers, “What would encourage you to walk, bike, or take Chicago Transit Authority more?” A passenger’s response, sent via text message, triggered a reply inviting the passenger to visit a website where other people who texted similar keywords — and who consequently shared similar interests — gathered in so-called Action Groups. (The user interface, modeled on a series of Post-it notes, was also designed by Local Projects.) Members then connected to nonprofits or block associations that shared their goals.

New York’s Give a Minute, however, envisions a busy two-way street running between users and Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s office. Dovetailing with the mayor’s PlaNYC 2030 sustainability goals, Give a Minute’s inaugural question asks New Yorkers, “How do we make greener neighborhoods?”

“We’ll be reaching out to a range of stakeholders and saying, we have some ideas, you have some ideas, how can we come together and improve sustainability in your community?” says New York Deputy Mayor Steve Goldsmith. The mayor’s office is so bullish on the project’s approach to public engagement that it is offering “substantial grants” to groups and individuals who use the Give a Minute platform to effect positive sustainability outcomes, whether it’s more tree plantings on a block or a surface-water collection process that prevents sewer overflows.

“We’re not trying to control the conversation to fit some hierarchy,” Goldsmith says. “Collaborative exchange around important issues like sustainability is a positive outcome in and of itself.”

For his part, Barton hopes the majority of Give a Minute participants apply their own wits and resources to realize their goals. “Very cellular, local groups, and not just big not-for-profits, should be the primary movers of this platform,” he says.

If New Yorkers embrace Give a Minute as enthusiastically as their public servants have, solutions to city life’s most vexing sustainability issues could come not from an agency office, but from a classroom, a social club, or — horror of horrors — a Tweetup.