Update: I’m happy to report that in 2013, two years after this post was published, Google improved the labelling of river names, and indeed you can now find the Atchafalaya (and the Delaware, Columbia, Seine and Mississippi) on the base map. [JW]

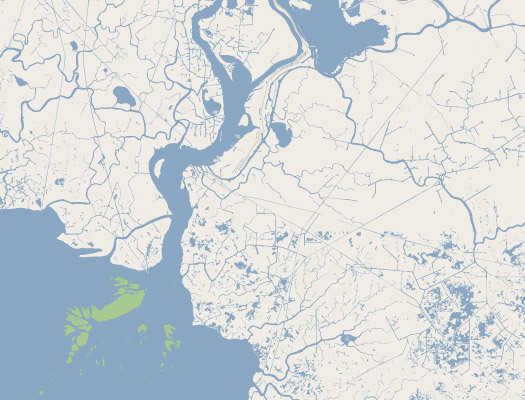

Do you know where the Atchafalaya meets the Gulf of Mexico?

If you're John McPhee — or if you've ever jumped a Gator-Tail mud boat through cordgrass — of course you do. The rest of us, we have to look it up on the map. Reading Kristi Dykema Cheramie's fascinating essay about the Mississippi River Basin Model, we scramble to learn more about the names we encounter: the Atchafalaya, the Cumberland, the Bayou Lafourche. Part of the pleasure in reading essays like this on Places is imagining ourselves as giants in a miniature world, standing, with Cheramie, "astride the river, with one foot on the plains of Vidalia, Louisiana, and the other on the bluffs of Natchez, Mississippi."

Atlases are old and heavy, so we turn to our own technocratic marvel of geo-visualization: Google Maps. In less than six years, the Google Map (singular!) has displaced National Geographic, Rand McNally, and the globe in your grandmomma's den as the dominant way of seeing the world. No map in history has made us feel more powerful or more present, able to fly to Cairo and Libya with a flick of the mouse, then zoom in on Jackson Square, New Orleans. On a touchscreen, we pinch and spread. No map has so fully rewarded our curiosity.

And no map has so completely bollixed the depiction of rivers.

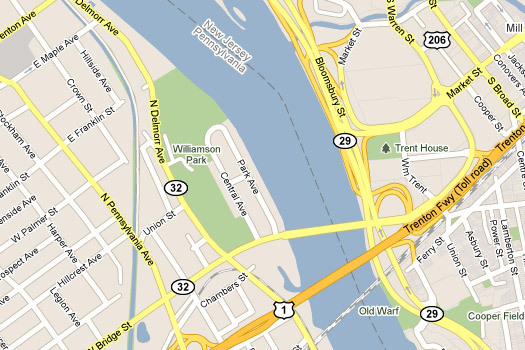

Quick: What river did George Washington cross at the battle of Trenton. Was it Old Warf?

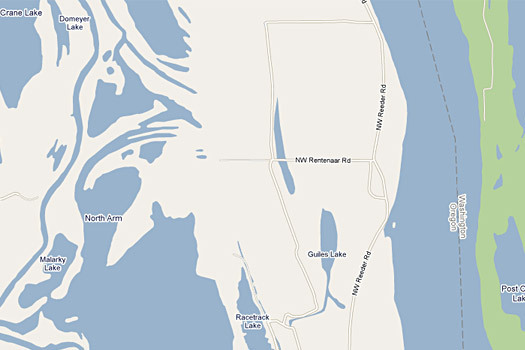

What's that blue line on the Washington–Oregon border? You know, the really big one that early explorers thought was the Northwest Passage? Here's a hint: It connects Malarky Lake to Bower Slough.

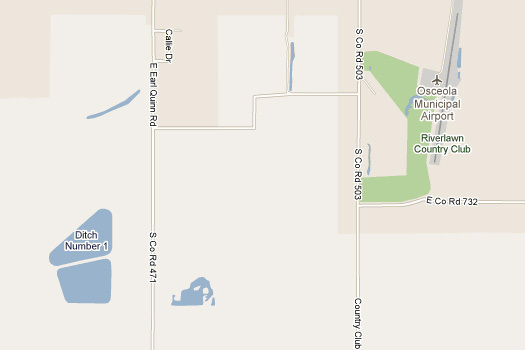

Somehow Google can give us the name of every dinky lake, backwater, and canal on Portland's Sauvie Island, but not the name of the mighty Columbia River. River names are conspicuously absent around the globe, in rural and urban areas, in plains and mountains, in coastal and inland areas, at every zoom level. We may not have La Seine in Paris, my dear, but we'll always have Ditch #1 in Osceola, Arkansas.

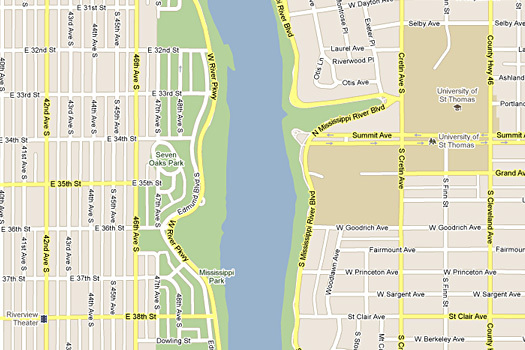

Parents, teach your children the name of the muddy water that separates Minneapolis from St. Paul. God knows they're not going to learn it on the iPhone.

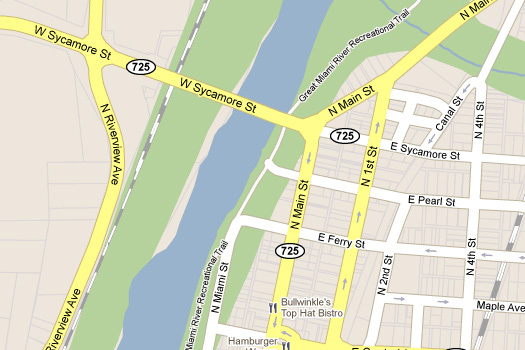

Fly with me now to Miamisburg, Ohio, home of the Miamisburg Indian Burial Mound, the Mound Golf Course, and the Mound Laboratory, operated by Monsanto Chemical Company, which produced bomb detonators and recovered tritium from nuclear weapon components during the Cold War, discharging chemical and radioactive wastes into the river. Miamisburg is named for the Miami nation; Miami means "downstream people." Here we find Miami Street and Riverview Avenue and, if you zoom in, a bike path, the Great Miami River Recreational Trail. It runs alongside a mysterious body of water. You'll have to guess what that's called.

It's easy to let the mapmakers off the hook. You could say, well, rivers are long and words are small; maybe the names are lost five hundred miles upstream. But Google manages to label streets and highways every twenty feet; surely they can do the same with rivers and creeks. Alternatively, you could argue that rivers are physical features, like forests and mountains, that don't belong on a political map. But anyone who's ever traced the Arkansas–Tennessee border through the Brandywine chute understands that rivers are inherently political. How can we talk about watershed health if we don't see river names on the map with our political boundaries, with our farm towns and factories and Superfund sites?

I've just spent the last half hour looking for the mouth of the Atchafalaya, following a corpulent blue squiggle, pixel by pixel, 170 miles from the Mississippi confluence to the Gulf. At close zoom, it's easy to get lost in southern Louisiana. The river splits a dozen times as it flows through the swamp, and twice I took a wrong turn, at Long Lake and Yellow Bayou. (These are labeled on the map, of course; you know you've lost the river when you find a place name.) No Atchafalaya.

Sure, you can find river names in Google Earth, and in the terrain view of Google Maps (although the coverage is not as good as you might think). You can even switch to street view and walk the little Keith Haring guy (his name is Pegman) down to the bank to look for a sign by the bridge. It's thrilling to have these advanced map features — O, these many ways of seeing — but they don't have the same impact. Terrain view doesn't work at high zoom levels, and Google Earth crashes my old laptop. I want to see the Atchafalaya on the Google Map, the one they call "map view" (like, duh!), the one we see at night when we close our eyes and dream of flying. That's the one that counts.

If you promise to keep a secret, I can tell you there are river names hiding here and there among the blank spaces on the Google Map. I've found the Hudson and the Sacramento. The Nile is named in two languages. The Drina is labeled in Cyrillic, although the river itself has disappeared from Višegrad, home of the great novel by Ivo Andrić. But these sightings are rare, and I dare not link to the geocoordinates. Google watches over us all, and I don't want to wake up tomorrow to find the Sacramento River erased like the mere Mississippi.

City planners, designers, change observers, will you join my cause? Google Maps Maniacs, Mapperz, OgleEarthlings, are you with me? Google, do you hear us? ATCHAFALAYA!