Firefly Design That Matters (DtM), founded by Timothy Prestero, creates context-appropriate medical devices for use in developing communities. Global health experts estimate that 5–10 percent of all newborn mortality is due to jaundice, a condition easily cured by shining blue light on the baby’s skin. Firefly is designed to allow rural hospitals to treat otherwise healthy newborns for jaundice at the point of diagnosis, rather than risk transporting them to crowded central facilities. Unlike the conventional devices received through international donations or government purchases, Firefly provides high-intensity phototherapy that is “hard to use wrong,” removing common sources of product failure. The rounded, seamless bassinet can be wiped clean in seconds. The outer casings have tight seams and no vents, which prevents insects, dust, and liquids from damaging the device or dimming the lights. Internal moving parts have been eliminated, including fans, which can be easily broken.

Editor's Note: The following text and images are an excerpt from, Health Design Thinking, 2nd Edition by Bon Ku, MD and Ellen Lupton, and reprinted with permission of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Institution and MIT Press. We are hosting Bon Ku and Ellen Lupton for a lunchtime discussion on Wednesday, March 2, 2022. Tickets here.

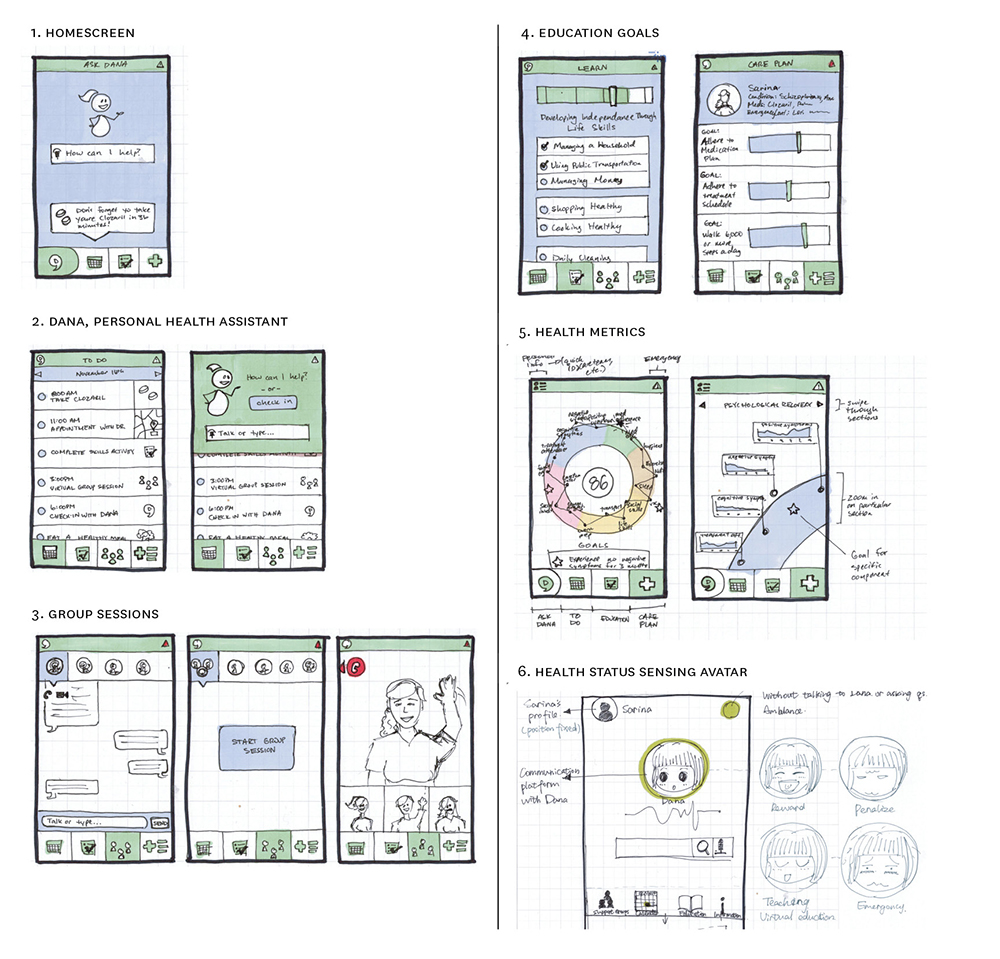

Storyboards These screen designs represent a digital app for patients with schizophrenia. This complex app includes a calendar for self-care, video group sessions, medication tracking, patient education, and overall health metrics. More complex features are explained with multiple screens. Design: GoInvo

Health design thinking is an approach to generating creative ideas and solutions that enhance human well-being. Health design thinking is an open mindset rather than a rigid methodology. Anyone can participate in this process. Listening, observing, storytelling, prototyping, and role-play are tools for building empathy and thinking creatively.

The first edition of Health Design Thinking conveys ideas and methods that have been applied to products, environments, and services. This new edition builds on those fundamentals in light of the changes in design and health care prompted by COVID-19. When the pandemic hit, clinics, schools, and design offices were forced to immediately provide services online. Policy failures, misinformation, and political manipulations exploited frontline workers. Marginalized communities demanded equitable care. Catastrophic gaps in the global supply chain demanded the design and redesign of personal protective equipment (PPE), mobile testing, remote care, and safe, inclusive ways to use public and private space.

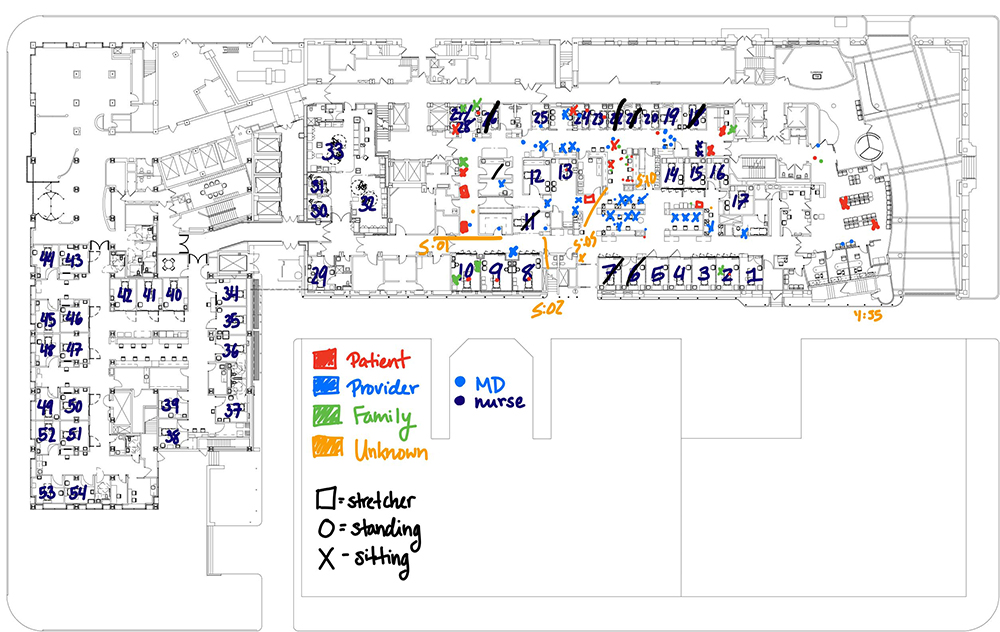

Spatial Data Mapping Thomas Jefferson University Hospital worked with architects KieranTimberlake to explore how space is used in the emergency department. Using a snapshot approach to collecting data, medical interns mapped the location of occupants every hour over a forty-eight-hour period. They color-coded the data to distinguish among clinicians, patients, staff, and family and friends. Early paper prototypes like this one led to the creation of the final digital workflow, which uses geographic information systems (GIS) mapping software.

Health Design Thinking, Second Edition is a field guide for rapid-response design. Our underlying methodology emerged from the Health Design Lab at Thomas Jefferson University, co-founded by Bon Ku. The Lab began as an experiment. Could medical students with no engineering background create prototypes for new devices and services? During the pandemic, the Lab switched gears to confront such challenges as manufacturing nasopharyngeal swabs for detecting SARS-CoV-2 and deploying mobile testing and vaccination sites in underserved neighborhoods.

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum joined forces with the Health Design Lab to create and update this essential guide for doctors, nurses, educators, students, patients, advocates, architects,and designers. Design thinking will continue to grow, becoming a crucial tool as hospitals, governments, caregivers, and communities prepare for the future.

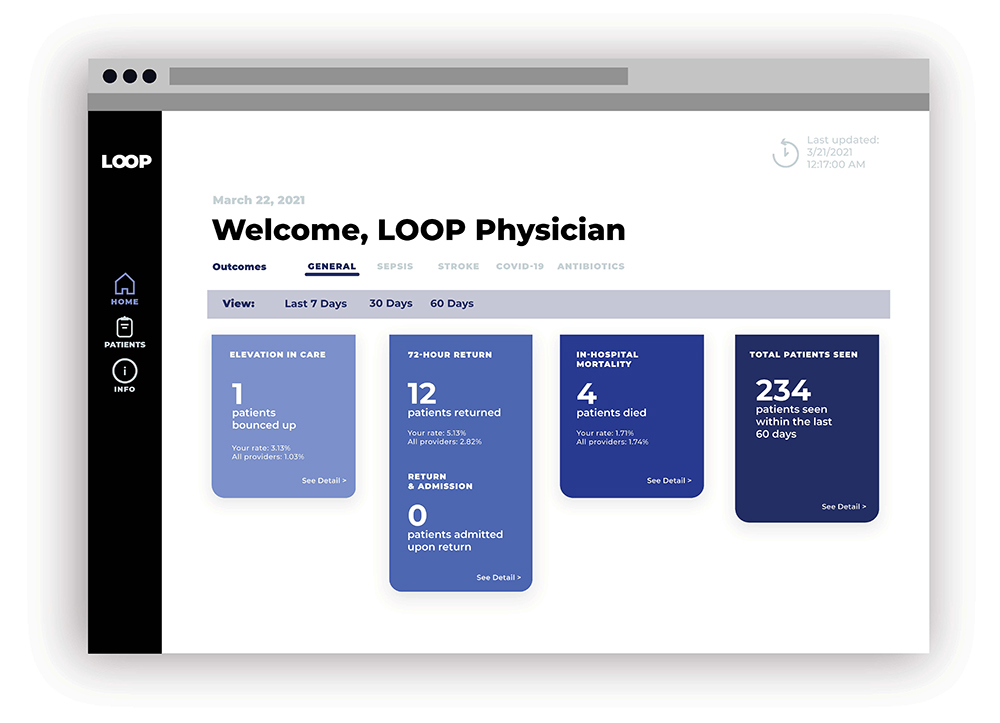

Codesign with Physicians An interdisciplinary team at the Center for Social Design at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) collaborated with Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Center for Data Science in Emergency Medicine (CDEM) to reduce the disconnect between emergency medicine clinicians and their patients. They prototyped a digital tool allowing emergency physicians to track what happens to their patients after leaving the emergency department.

Design Sprint Katie McCurdy and Jeremy Beaudry conducted a three-day design sprint with staff at the University of Vermont Medical Center (UVMC) as part of their work researching problems with wayfinding (how to navigate the hospital campus). One idea was to depict the hospital as a landscape, consisting of a mountain and a forest connected by a river. McCurdy recalls, “We printed paper signs and tested the concept in the real space of the hospital, getting feedback from visitors and spreading awareness of the project. This was a novel approach in what is typically a rigid environment.”

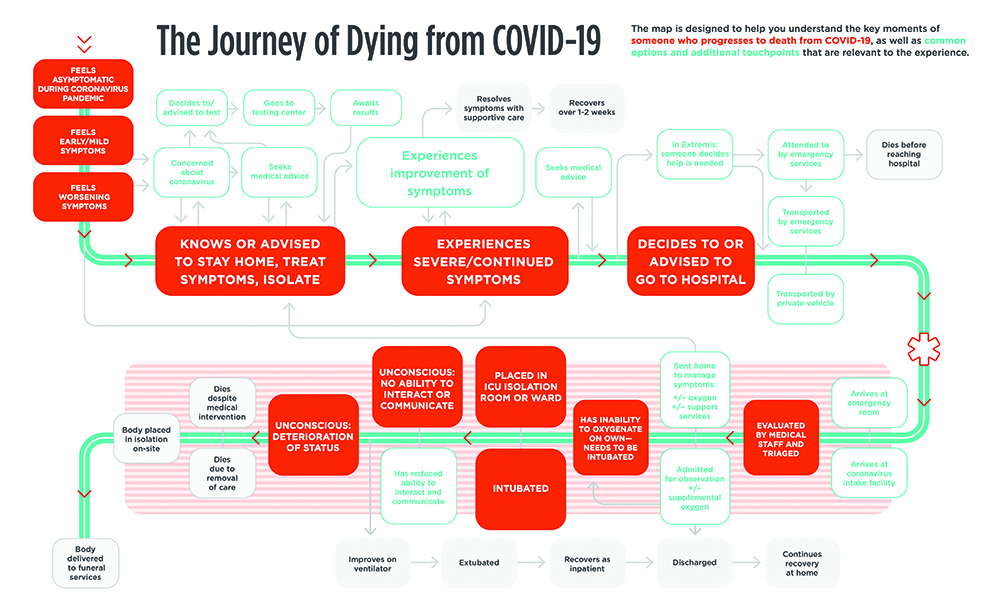

The Ultimate Journey Designers at the Emergency Design Collective and Blumline created this journey map early in the COVID-19 pandemic. When patients enter the hospital incapacitated, clinicians are often forced to make decisions about ventilators and other interventions without full participation of the patient and family members. This journey map led Blumline to create “Famous Last Words,” a tool for holding guided conversations about life, death, and dying. Design team: Strategy: Natasha Margot Blum; Architect: David Janka; Design: Alana Ippolito; Illustration: Andrew Holder

Demand for Chlorhexidine The US Agency for International Development (USAID), in partnership with Dalberg Design, applied a design thinking approach to spark demand for chlorhexidine, a treatment for newborn umbilical cord care that is low-cost, simple to use, and easy to manufacture. The design effort focused on Nigeria, a country that had been developing its own national scale-up strategy to generate demand for chlorhexidine across caregivers, health care workers, and the private sector. A blended team including designers, donors, and implementing partners interviewed mothers, held community and professional workshops, shadowed birth attendants, and visited homes, antenatal clinics, and drugstores to understand the concerns informing decisions about umbilical cord care and to define the value proposition of chlorhexidine.