Editor's Note: Michael Horsham's Hello Human: A History of Visual Communication is out now from Thames & Hudson. Recently, Adrian Shaughnessy, Michael Horsham, and our co-founder Jessica Helfand discussed the role of artificial intelligence in the production of creative visual work. You can watch the conversation here.

What is visual communication? Anyone who works in graphic design, advertising or any of the related fields will have no doubt about the term’s meaning: it’s the stuff that professional communicators of all stripes brandish in our faces every day. But does it have a wider meaning? Does it include texts? What about flags, architecture, the podiums used by government spokespeople? And what would the fabled “person in the street” say that it meant?

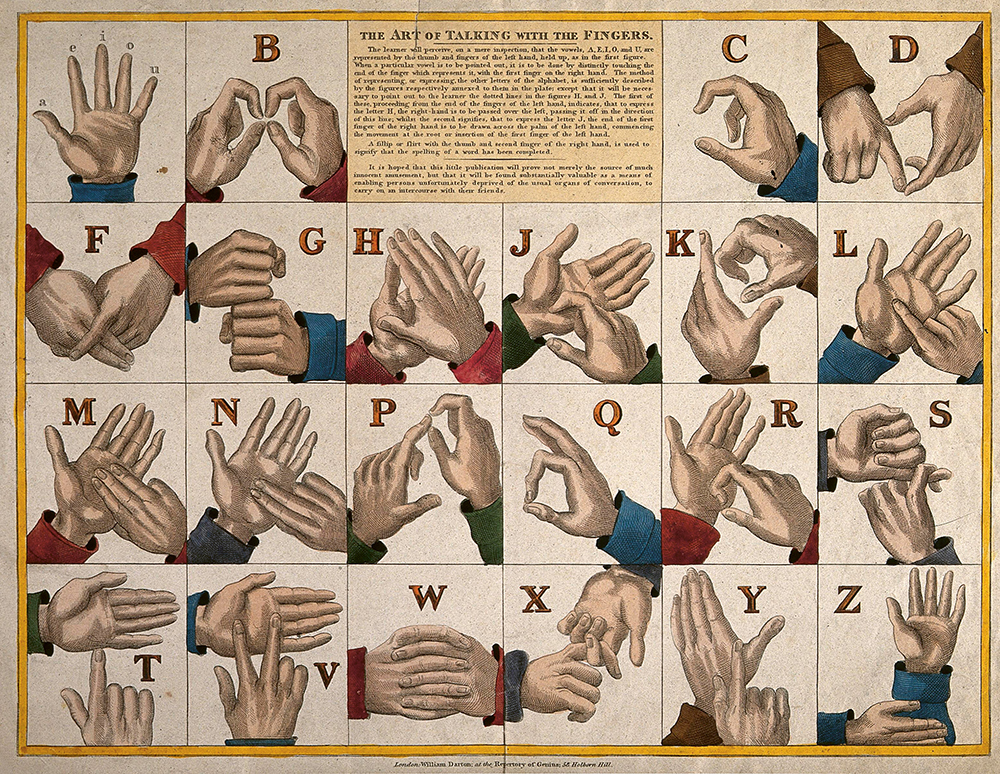

Michael Horsham’s book, Hello Human: A History of Visual Communication, rapturously tell us that visual communication means all the above and much else besides. He begins with cave paintings and the primal properties of the hand — both as a tool for image-making and for its gestural capabilities (Stop!). He trawls through the scribal activities of medieval monks, the development of calligraphy, and pre-Gutenberg printing technology. He stalks the iconography of modernism, the jet-propelled symbolism of space exploration, finally arriving in the digital era with its fake images, memes, emojis, and the dopamine-laced, always-on domain of social media.

British sign language, 19th century poster. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection

It's easy to be overawed by Horsham’s scholarship. No reference is left unexamined. Hidden histories are chased down and exposed with a dogged determination to get to the taproot of everything he turns his attention to. Horsham is well placed to make a survey of this vast and mercurial subject. He has a degree in design history. He is a member of tomato, the hybrid collective that straddled international design in the 90s and early 2000s and which retains an enigmatic presence in today’s design scene. At various art schools, he has been an extremal examiner, visiting professor, and course leader. He calls himself “an independent thinker/maker and doer”.

To the task of writing this book, Horsham brings that rare combination of pedagogy and practice. As both ethnographer of images and maker of visual communication, Horsham has the intellectual and practical chops to reveal the cultural and historical underpinning of everything he mentions, as well as a working knowledge of the technical skills and tools necessary to make visual work of all kinds.

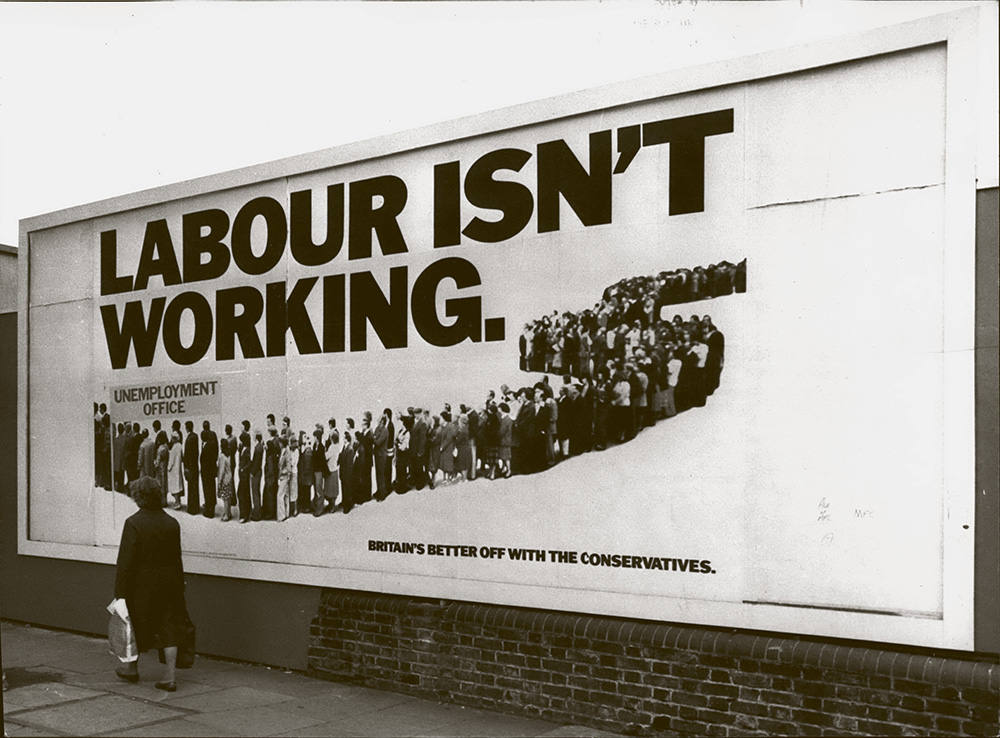

Sometimes the scholarship becomes a distraction. There’s a sense of him riffing on the stuff that excites him like musicians enchanted by the possibilities of their instruments. But you never mind being sucked into one of his pedagogical riffs. There’s always something to be learned: the origins of the PDF; the activities of the 14c Lollards in the development of printing; the semiotics of the CND and Extinction Rebellion logos; the taking of the knee by Colin Kaepernick; and the adoption of Surrealist tropes in 1970s British advertising. It’s a protein-rich brew of the arcane and the quotidian.

"Labour isn't Working" poster. Image from Keystone Pres/Alamy Stock Photo.

The occasionally overwhelming history is leavened by an ability to find telling examples to illustrate key points in his text. Horsham deftly marshals a host of disparate reference points to supercharge his argument: everything from a Texas lawyer appearing on Zoom as a cat to the emblematic power of Kim Kardashian. He easefully ranges across pop culture to the latest scientific discoveries.

But what is his argument? This is not a polemical book, although the reader is in no doubt where Horsham’s sympathises lie — he’s a fierce advocate of the need to retain our humanity in a world of machine-driven alienation; he rails against work-place surveillance; and he urges us to be outraged when “we feel we are being lied to, scammed, manipulated or controlled”. The book stands as bold attempt to map the history of a subject so prevalent we risk never stopping to ask what it is.

Steward Brand pasting up the WEC. Image from Richard Drew/AP/Shutterstock.

Which raises the question — who is the audience for this survey? Anyone in the design world will benefit from reading Horsham’s text, but only so long as they are not looking for a neatly packaged definition of visual communication. Horsham doesn’t give one — perhaps because there isn’t one, just as there is no longer a single definition of art, graphic design, or truth in a post-truth world. Instead, this is a book that can be profitably read by anyone interested in the sometimes utopian, sometimes dystopian image-world we all inhabit.

There’s no doubt that Hello Human would find a ready audience if it confined its terrain to the contemporary visual scene. But it would be less of a book and less of a contribution to understanding something we encounter every minute of our waking lives.