1.

In part three of Jerome Seckler’s interview with Matisse the tone has shifted yet again. It is both more easy-going than part two, with moments of relaxed humor, as well as more technical in terms of Matisse’s explanation of painting techniques. Toward the end there is an unexpected analysis of the state of American painting.

The humor is almost always self-deprecating. When Seckler asks Matisse about his influence on a younger generation of artists, and suggests that Matisse has changed the course of painting, Matisse replies: “It’s not my fault. I didn’t do it on purpose.” You can imagine both of them laughing.

Seckler then shifts to a more pragmatic, process-driven line of questioning about perspective, rhythm, line, and color theory. Matisse’s answers are specific and illuminating.

There is a lesson here about the vexed question of how to interview an artist. In a 1941 interview for French Radio, Matisse was asked the following open-ended question: “to express yourself, how do you go about it?” In part, he replies: “as to my drawing, I follow my inner feelings as far as possible.” The answer is general, abstract, and not all that original.

How different that is from this interview, in which Matisse, spurred on by a granular back and forth with Seckler about technique, then talks us through a fascinating description of how rhythm functions in one particular work of art. Artists are usually thrilled to talk about the nitty-gritty of how they do what they do.

There is a riveting section toward the end where Matisse discusses American art. He visited the States in 1930 (he stopped in New York, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles, before sailing to Tahiti from San Francisco) and he poses astute questions and makes some bold pronouncements.

Presciently, Matisse seems to forecast the ascendency of the Abstract Expressionists: “bad boys” who needed to rely heavily on “instinct” to produce work in a culture that lacked a deep painting tradition (at least, for Matisse, compared to France).

2.

In the spring of 1946, when Picasso made his visit to Vence, he and Matisse had talked about the effect the two of them would have on that next generation of artists.

Matisse pulled out catalogues for both Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell. Picasso and Matisse poured over their paintings. “What do you think they have incorporated from us?” Matisse asked. “And in a generation or two, who among the painters will still carry a part of us in his heart, as we do Manet and Cezanne?”

3.

While walking through the current exhibition at MoMA, the question, is, rather, what do we all carry in our hearts as a result of the cut-outs?

Their impact and originality have become defused by their endless reproduction on postcards and dorm posters. But at MoMA you can see them afresh. Starting from the first room of the exhibition it’s their physicality which is so striking—the push pin constellations where they have been moved and re-pinned, the still shocking vibrancy of their colors, and, in the final rooms, the sheer astonishing size of them. The exhibition returns the cut-outs to their visual context: radical expressions of the pure power of color and form.

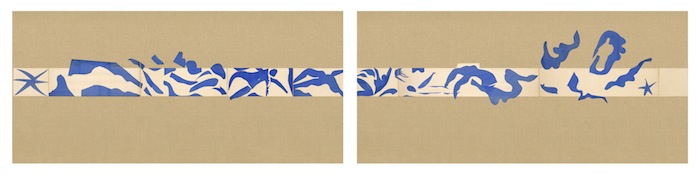

Seckler’s interview took place when Matisse was making the two large pieces that would become Oceania, The Sky and Oceania, The Sea. They occupy two entire walls at MoMA and they anticipate, as a site specific work, one of the highlights of the exhibition, the refurbished The Swimming Pool (1952), the fifty-four-foot cut-out that is part of the permanent collection of MoMA (and which Karl Buchberg, the chief conservator, devoted five years to restoring, and which was the genesis for this exhibition).

Like Oceania, The Sky and Oceania, The Sea, The Swimming Pool spreads laterally across walls, an outward manifestation of Matisse’s inward vision, and which, like the 1946 work, Matisse made for his own domestic space, this time in the Hotel Regina in Nice. MoMA has reconstructed this room to the original scale.

Exhibition goers cluster in that room, looking upwards at a swimming pool that has been distilled through Matisse’s distinct sensibility, just as he had filtered his memories of Tahiti back in 1946. Matisse’s initial impulse in the middle of the night that summer to cover a stain on the wall with a cut-out of a swallow would eventually lead him, years later, to an aquatic “all over” series of cut-outs that is an astonishing example of his mastery of the form.

4.

In Part I of this series we saw that the first question Seckler asked Matisse was about the importance of the subject in his work. Matisse demurred, saying it was too complex a question. But he then made a simple, yet profound, statement, one of the highlights of the interview: “The subject is myself and what I see.”

Perhaps this is what held Picasso and Francoise Gilot “spellbound in a state of suspended breathing” when they witnessed Matisse, armed only with scissors and some colored paper, at work on the cut-outs: the singular vibrancy of his vision.

In the interview Matisse also stated “one should make a stimulating art which leads the spirit of the spectator into a domain which puts him outside of his annoyances.” As the crowds at MoMA attest, the aesthetic pleasure of the cut-outs still impressively manage to take us into that domain today.

++

JS: I love your paintings, but I want you to paint something else. Not a woman, something else.

HM: The Good Lord who is a great deal less hard to please than you gives you the possibility to paint, but is not able to make you paint everything no matter what. The artist changes the motif. One can say the same thing with always the same means. Raphael always painted the same motif. It is not always the same expression. It is the pretext, and if I don’t make the same expression it is because nature is varied, the thought gives different expressions. One must work a long time in order to render those things. Why make me make different things. I get into communication with nature by certain things. Why look somewhere else?

JS: When we look around at the young contemporary painters we see the tremendous influence of your painting. You have certainly helped change the direction of painting especially by your color.

HM: It is not my fault. I didn’t do it on purpose.

JS: Do you use color scientifically? What is your theory of color, especially as regards your conception of perspective?

HM: No, I don’t use color scientifically. And I have no theory of color. I haven’t any theory, even of drawing. That comes only from what I know what to look forward to. I work while waiting what will come. When I began painting, I copied the paintings in the Louvre and I finished by clarifying all that I thought and to see that color is a very beautiful thing. Why mix up the colors. Why trouble with all that. Why not utilize these colors as they are naturally. I searched for my combinations with combinations of colors which do not destroy themselves. In my [spirit], perspective is made in my head and not on the paper. That depends on you and the ideas you have. The most simple things are the most difficult. Can one understand why one doesn’t make the perspective like the Italians? The primitives also didn’t have perspective. One must see the colors as sonorities. A musical chord has a particular expression. You have the harmonies of colors, which have particular resonances. All music is made with seven notes. With that, one makes all the relations. Painting is the same thing.

JS: Don’t forget that we have rhythm in music. For example with one simple note you can have any number of different feelings according to the different rhythms.

HM: In the composition (drawing) you also have rhythm. My compositions gain also by their rhythm, which makes life. It is the rhythm which makes my composition no longer have the same aspect. Look at that drawing on the wall, the woman leaning her chin on her hand. That arm is not actually like that. It is too thin. But I changed it to create a better rhythm. And look at that drawing. The neck has not the same qualities as the clothing. The change in rhythm creates the change in quality.

JS: What would you say is the relation between form and color?

HM: It is complicated. That goes together [Matisse clasps his hands] like this. That handles itself. It is like a man and woman.

JS: From what I’ve seen of French painting it seems to be mostly a dash of Picasso, a dash of Matisse, a bit of the primitives and voila!

HM: Yes, it’s a cocktail.

JS: In what direction do you think the younger French painters will go?

HM: I can’t know everything. One can’t predict.

JS: The United States is a new country with great strength

HM: In America your artists have a great deal of strength, but have they the voice? You can have a great many musicians, a great many singers, but not have any talent. In America are there painters who make things as strong as jazz. One must have sensitivity in lack of tradition. One must have the instinct. I believe that in America there are not enough bad boys, some of bankers who do not wish to be bankers, who do not wish to be business men. One makes artists with dreamers. You can have all the strength, if you do not have the gifts you will not arrive.

JS: What do you think of abstract art?

HM: There abstraction and semi abstract art. I know nothing. I do not understand. Not to use the language of the world, it must have something to say. If you do not get what you have to express you become a criminal. An abstract painter, if he feels the lines, there will be rhythmic lines. If he is a colorist, there will be pretty colors, this does not mean that it will be understandable. Does it come out of something human that can communicate?

JS: You must have something for man in the painting.

HM: You wanted to speak to me with a Marxist point of view about painting. I hope that you will change, because your spirit will evolve. It is the continual revolution. Myself also I live a continual revolution. I too am working for fifty-five years which trying to reform myself the most possible, without sticking to the same thing in what I am making.

JS: All painters are neurotics and put their neuroses in their paintings.

HM: Do you think that I am neurotic? Is it seen in my paintings?

JS: Can you explain your preference for painting women and almost never painting men?

HM: I paint women. If there weren’t women, I would paint flowers. I have chosen women because they have rhythms which please me, proportions, forms which please me. I will paint a man, an American businessman for example, with pleasure because what counts is to have a model who will be interesting. Look here at this portrait I did of [Sergei] Shchukin, for example. I cannot work with a pretty woman who is stupid. The first posing if she is pretty I lend her things. At the second sitting I find myself before nothing. I need a model with intelligence, sensitivity. There are men very handsome, very strong, muscled, only I find that one has a great deal more in the woman in order to make paintings, a great deal more than in man. I would like to paint wrestlers—that would interest me. Or ice hockey players. I would have liked to paint the skaters in Switzerland, but the doctor forbids me to go there.

All that the book by [Raymond] Escholier says about me is true. I reviewed it myself.

++

This interview is published by permission of Donald Seckler. I'm indebted to Hilary Spurling’s Matisse the Master. The editors would like to thank Marisa Nakasone for her transcription help.

Images:

Henri Matisse, The Codomas (Les Codomas), 1943. Maquette for plate XI from the illustrated book Jazz (1947). Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, mounted on canvas. 17 1/8 x 26 3/8” (43.5 x 67.1 cm). Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Dation, 1985. © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Henri Matisse, The Swimming Pool (La Piscine), late summer 1952. Maquette for ceramic (realized 1999 and 2005). Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, on painted paper. Overall 73 x 647” (185.4 x 1653.3 cm). Installed as nine panels in two parts on burlap-covered walls 136” (345.4 cm) high. Frieze installed at a height of 65” (165 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mrs Bernard F. Gimbel Fund, 1975 © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

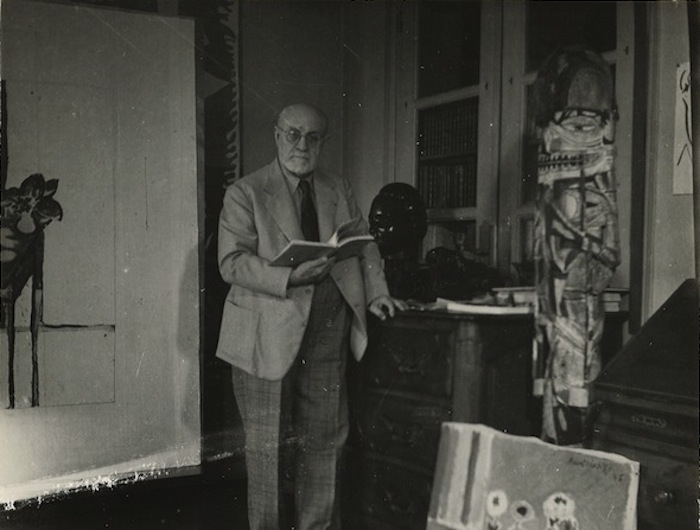

Henri Matisse, Paris, August 1946. Photo courtesy Donald Seckler