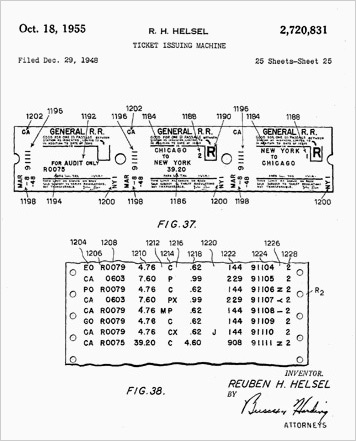

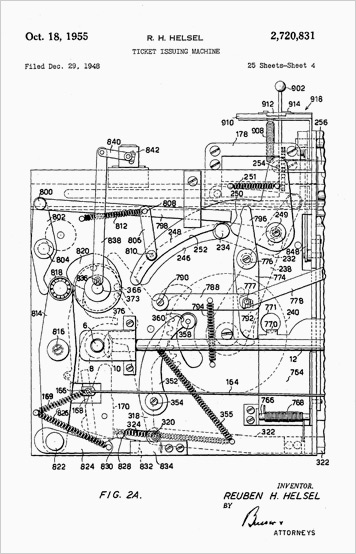

The transit ticket issuing machine, patented by R. H. Helsel, 1955

Tickets: the most ephemeral of all ephemera, the rarest category of paper collectibles. Designed to be temporary stand-ins for a box at the opera or seat on the train, they were never meant to have any real permanence. After all, the conductor or person taking the tickets at the gate rips them in half. (Until recently, that is, when admission is determined by simply pointing a laser scanner at the bar code printed on an e-ticket.) Throughout history, tickets have been made of everything from ivory to semiprecious metals, to paper or card stock, to the bits and bytes of their current digital format. Even now, every journey still begins, literally or virtually, at the ticket window — an always-recognizable point of reference in unfamiliar surroundings. Tickets endure despite their temporal quality because they provide a way to orient ourselves logically and precisely on the giant invisible grid of daily life.

The dawn of the 20th Century in America marked the beginning of unbridled hope for a better future through technological advances. People shared the belief that machines would make their lives easier, better, and more fulfilling, and this was borne out by the increased amounts of leisure time and affordable travel brought about by the Machine Age. To see a play or movie, or ride the Twentieth Century Limited, you needed a ticket, and the development of ticket-dispensing machines paralleled the growth of popular culture, allowing the entertainment and travel industries to efficiently serve greater numbers of citizens hungry for fun and adventure.

Small inventors played a huge part in creating this world of optimism, and Reuben Harry Helsel, of Long Island City, was a typical unsung hero. A shrewd observer of the era he lived in, he invented every sort of ticketing device imaginable, patenting 45 different machines between 1917 and 1962 across a spectrum of applications, from streetcars to cinemas to racetracks. A closer look at a couple of his creations illuminates the design climate and social conditions that allowed innovation to flourish during the Machine Age and postwar years in America.

Tracking the improvements to each of Helsel’s patents offers a rare glimpse of the design process operating in a nearly ideal environment: there was demand for the product (and money available for its research and development), healthy competition for customers, and plentiful opportunity for an inventor with a sharp eye to stay one step ahead of current trends, designing something new just as the need for it materialized.

Today the ubiquity of moving pictures has rendered them unremarkable; from digital billboards to smart phones, recorded images in motion are a normal, expected component of our visual environment. But at their inception, moving pictures represented a cultural earthquake of incredible magnitude. In 1895 the Lumiére brothers’ first private screening of a film of a locomotive train caused a stampede as terrified viewers charged the exits, fearful of being crushed by the oncoming steam engine. The next decades brought rapid advances to the cinema, adding sound and increased picture quality, and finally the glory of full-on Technicolor in 1935. Far from the glamorous world of Hollywood stars and directors, a guy from Queens realized that as films increased in popularity, the humble ticket issuing machine would become a critical piece of hardware.

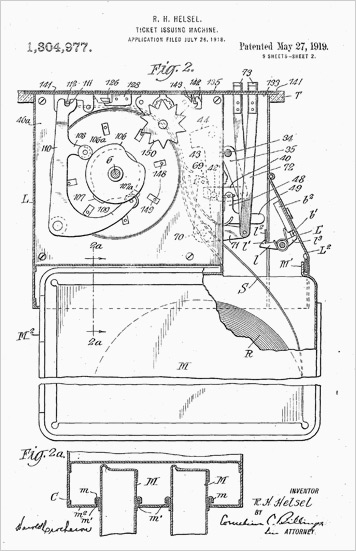

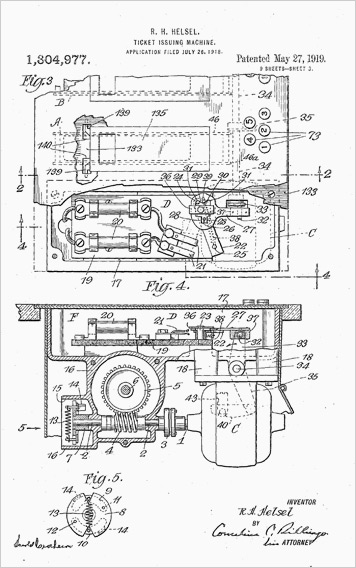

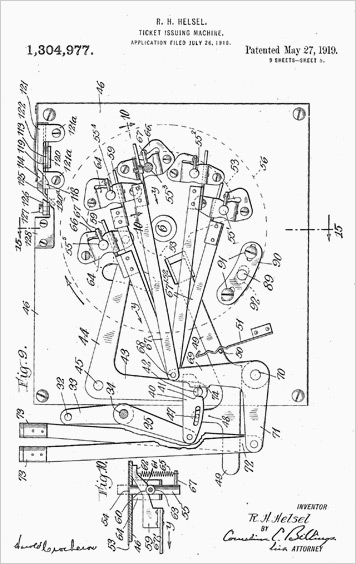

Above images: the movie ticket issuing machine, patented by R. H. Helsel, 1919

Helsel’s first theater ticketing device was patented in 1919, the same year that Charlie Chaplin joined forces with D.W.Griffith, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford to establish United Artists. The year also saw the end of WWI, and the start of Prohibition: heady times. Even at this early stage of the public’s obsession with the movies, Helsel foresaw the necessity to move ever-greater crowds of people quickly past the ticket booth and on to their seats. His patent #1,304,977 provides for a machine to dispense tickets in varying quantities and denominations in a single speedy operation. The machine also displays the kind of design functionality epitomized by the ideals of the Machine Age: its numerical keys, once selected by the operator for ticket price and quantity, remain sunken flush into the stainless-steel counter until the end of the transaction, so the money and tickets can slide smoothly across. In keeping with Henry Ford’s philosophy of mass production sweeping the nation’s industries, all the parts of the machine were designed to be stamped out of inexpensive sheet metal, and interchangeable for ease of maintenance and replacement.

Apart from his mechanical aptitude, Helsel was able to accurately analyze the human factors in play and correct any difficulties encountered by the users. In later decades Helsel patented improved mechanisms for self-sharpening knives to sever the tickets cleanly from their strip inside the machine; the use of smudge-less transfer ribbons to print the date, price, and time of show onto a preprinted ticket blank without leaving ink on the customer; and a carbon-copy journal sealed within the machine as an accurate record of the number of tickets sold, their price, and show times. The archiving of data would not only allow theater owners to quickly identify theft, but also provide useful information as to which shows were most well-attended.

Accountability was one of Helsel’s most significant contributions to transportation ticketing machines as well. His earliest patent of this type was in 1922, for a coin-operated streetcar ticket dispenser, but as rail and air travel took off during the late 1930s through the 50’s, he focused his attention on these newer modes of transportation. Prior to automation, the travel ticket-issuing process was cumbersome and vexing, as large amounts of information had to be handwritten or stamped onto each ticket. Here’s some painful math: imagine a group of four, at the head of a long line of passengers waiting to buy tickets at Grand Central Station. They plan to travel across three railroad zones during a busy holiday weekend. Now imagine how long will it take an agent to hand-write their 32 roundtrip tickets and transfers. Ouch.

Above image: the transit ticket issuing machine, patented by R. H. Helsel, 1955

Besides its slowness, the ticketing process was ripe for fraud and theft. Each ticket agent in a station had his own individual case of tickets for which he was responsible, with a potential cash value of hundreds or thousands of dollars. The cases were locked away when agents were off duty, but stolen tickets could be used by anyone as there was no way of tracking them or canceling their value. Dishonest employees could keep part of the day’s take by writing in a lower fare than was actually collected and pocketing the difference.

Starting in 1952, Helsel patented and incrementally refined a ticketing machine that provided a straightforward design solution to both of these problems. The final patent, #2,822,975, approved in 1958, created a device able to rapidly print necessary information directly on to both simple and complex ticket blanks, and it also produced a tamper proof carbon-copy set of duplicate data with each operator’s unique I.D. code printed on every ticket sold. With the increased accountability, it became nearly impossible to skim cash.

Helsel’s foresight and careful observation continually advanced the design of the machines he spent a lifetime perfecting. His inventions didn’t call attention to themselves with futuristic dials and knobs, but operated elegantly unseen, hidden within sleek housings. As the streamlined look of massive trains and airliners communicated modern society’s love of increased speed and efficiency, improved ticket-issuing devices reflected this desire on a small-scale practical level. Tickets magically appearing from their slots in the counter at the theater or train station were the starting points of an evening at the movies or a journey to a new place, allowing new adventures in a world expanded by the capabilities of machines and the people who dreamed them up.