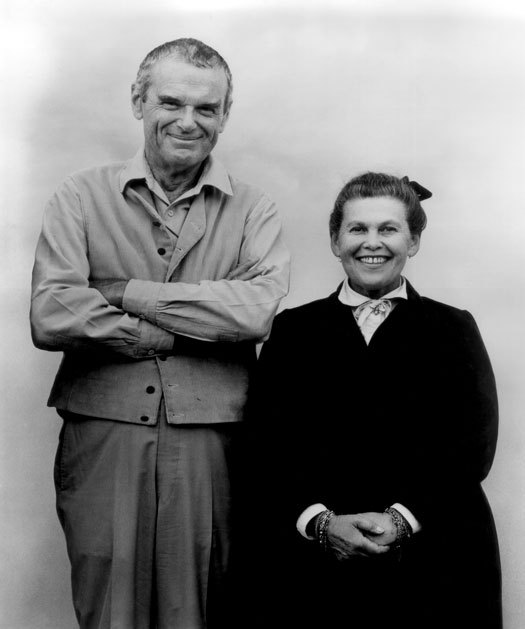

Charles and Ray photographed for the Connections exhibition in October 1976. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 2010

I don’t know what to do with this book. The Story of Eames Furniture, by Marilyn Neuhart with John Neuhart (Gestalten, 2010), is a labor of love, a two-part, richly-illustrated history of some of the most famous modern chairs in the world. To reject it seems harsh. It contains fascinating tales of false starts and under-known design careers, what could be a separate book of clever mid-century magazine covers, furniture catalogs, and abstract photographic odes to mass-production. And yet I was unable to enjoy it. It is the kind of book that the design blogs love, picking out 10 fabulous images, glorying in its heft entirely in the abstract. Another chance to cite the Eameses! But as a real thing and as a work of history, it is less than the sum of its pages.Physically

The Story of Eames Furniture is approximately 10 by 12 inches, taller than it is wide, in two volumes that are each 1.5 inches thick. It costs $125. The print is small, a serif body type black on glossy white pages. Captions, in single blocks, italicized, are even smaller. The 2,500 photos are also small, when they are not double-page spreads. In neither case is it easy to see what is happening in them, or to match caption to image. In my reading of the 800 pages, I found the only comfortable position to be propped up in bed with a pillow on my lap, bringing the book close enough to read but cushioning its weight.

The physical book Story of Eames Furniture by Marilyn Neuhart with John Neuhart

Visually

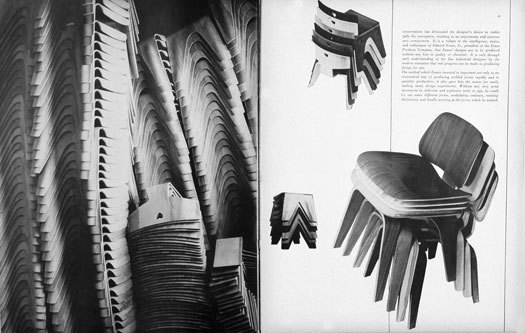

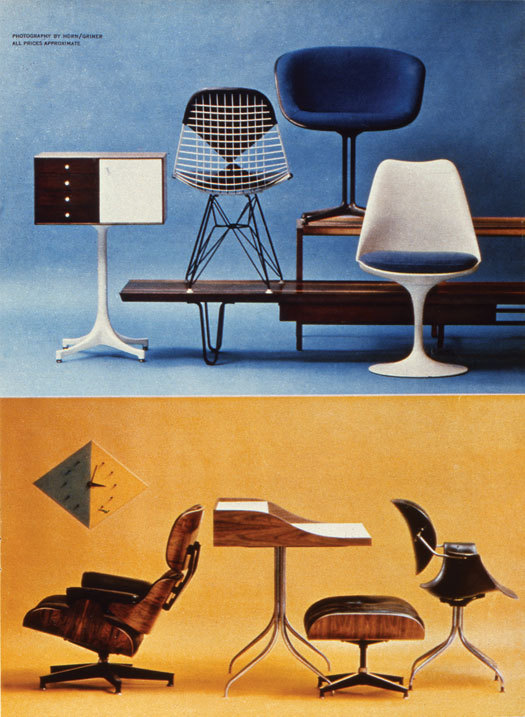

From Eames Furniture’s description, price and intended audience you would put it in the category of Taschen’s glorious mid-century show-pony books, Case Study Houses and Neutra, or Phaidon’s Le Corbusier Le Grand. But those three books are made for the library table, left open to L’Esprit Nouveau or a Julius Shulman photograph. They were made for flipping from one glorious vista to the next. This book is about furniture, and rather technically so. Many of the photos are of prototypes and patent applications, a chair below and a chair above. The Eames chairs have had as long lives, and possibly greater impact, than those California houses, but I don’t get more than a Chaplinesque thrill from the photos of a big stack of fiberglass shells. The glamour shots suffer from familiarity; I preferred the period ads, which show (where the text doesn’t tell) how the manufacturers positioned these strange new objects in the home. Eames Furniture, also designed by the Neuharts, isn’t a compelling design object. (See Mark Lamster on the cult of the big book.)

In a book which purports to give you the facts of the design process of a series of iconic pieces of furniture, and includes thousands of photographs, you expect the pictures to tell a story. That’s one of the things Charles Eames did best: take photographs and use the process of design to explain other processes, including computers, the history of science, the history of America, even numbers. But these pictures don’t tell a story. Each page is divided into a three-column grid, with the text taking two columns. Separated from the text by a rule are from one to four small photos. Sometimes there is another photo in the text column. Or a flurry on the opposite side of the spread. It was never clear to me why each image was placed where it was. The images fit the text loosely, but I found myself unable to see, for example, the moment when bent plywood took the decisive turn toward the form with which we are familiar.

In another example, Neuhart’s text begins with a series of short biographies, including one of Eero Saarinen with 20+ images of his work. But most of the architecture is reproduced too small to see its qualities. Two larger images, or a series of views of select buildings, would have done the job of description much better. It is amazing that Neuhart was able to include so many images (I can’t seem to get a book published with 150), but if they aren’t working, numbers don’t count.

Editorially

This is what really matters, particularly in an age when most dead designers get one book written about them at best. The Eameses are a special category, as the designers whose last name defines the era on eBay. There have been Eames books before, and there will be Eames books again. This is heartening, because that means Neuhart can’t have the last word — as she acknowledges in a rather startling introduction.

Marilyn and John Neuhart met the Eameses in 1952; John worked in the office from 1957 to 1961, and freelanced thereafter. Both were, as Marilyn writes in the introduction “in and out of the office in various capacities,” and worked with (“in spite of,” Neuhart writes in her introduction) Ray Eames on the book Eames Design. She writes:

Too much of the writing about them has often had a cloying, worshipful quality

that is at odds with the world in which they lived and worked. The deification

process is now well underway, aided and abetted by a number of people who

should know better than to apply to them the cult of celebrity without a careful

scrutiny of the facts…

Many will be upset by parts of this story; if they have to see Ray as a feminist

hero, they should stop reading now. If they need to see Charles as a romantic,

idealistic, larger-than-life, two-dimensional cardboard hero, they should stop

reading now. (Here she criticizes those with “long lists of academic credentials,”

and one must assume she means Pat Kirkham, whose biography is indeed a

feminist corrective, some would say over-corrective.)

Before we get to the furniture’s story, we first hear the stories of 22 collaborators, colleagues and employees of the various Eames businesses, the history of 901 West Washington (now Abbott Kinney) Boulevard which housed the office, the history of Herman Miller, and much, much more. While many of the figures Neuhart brings out are under-known — I was particularly interested in Charles Kratka, a graphic designer who worked for Eames between the rather famous Herbert Matter and Deborah Sussman — several are so well known as to make a five-page biography superfluous.

Page layouts of the September 1946 issue of Arts & Architecture. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 2010

Interior layout of the Eames Office as it was configured at the time of Charles Eame's Death in 1978. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 2010

Herman Miller has a cadre of books written about the company and De Pree family. Eero Saarinen got his own 400-page catalog (not cited in the footnotes) in 2006. Even Margaret Harris, with whose career I was not familiar, is known in the theater world and the subject of a joint biography. Eliot Noyes, who hired the Eameses to do films and more for IBM, gets not a chapter but a strange italicized sidebar. Why not just cite the book?All this front matter obscures the narrative Neuhart says she wanted to tell, “of something of how Eames furniture got to be the way it is. It examines one important aspect of the office work — furniture design and development. It is a biography not of a person but of a group of artifacts — their genesis and their development.” If this is true, then why does it take so long to get to the artifacts? She says she ultimately found the people and progress more interesting, but I am not sure how many readers will agree, particularly since the same period of Eames Office history is told and retold in those biographies (along with a lot of personal anecdotes). One longs to get to something we can see. And indeed, one of the many positive attributes of Eames Design is the way it lists all the people in the office at the time of a specific project.

I didn’t feel I got to the specifics of the furniture’s genesis and development until over 200 pages had passed. Neuhart’s story truly starts on page 250, when she discusses the 1940 Organic Design in Home Furnishings Competition at the Museum of Modern Art. This competition has a complicated history: Noyes and the MoMA play roles, Eames was working with Saarinen and others from Cranbrook on the submission, and the pieces designed in 1940 were never produced in their exhibited form. As a story of furniture production the winning Eames-Saarinen designs were a failure. As the germ of some of the most famous chairs of the 20th century they were a success. (See Peter Hall’s excellent essay on just this topic, “Uses of Failure.”) Because Neuhart is suspicious of interpretation, this story, the story of how the fiberglass shell and the pedestal chair came to equal American modernism, is not told. She bogs down in the iterations and false starts, paraphrasing the many interviews she and her husband conducted with Eames employees but too rarely letting them speak at any length in their own words.

Front and back views of Plyformed Products / Molded Plywood Divisions's molded plywood splints made for the U.S. Navy. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 2010

Experimental molded plywood lounge chair. Image credit: © 2010 Eames Office LLC, from the Collections of the Library of Congress

The 1940 competition lays the groundwork for all the future Eames chairs, bentwood and fiberglass and executive, as well as Saarinen’s iconic and rivalrous Grasshopper and Womb and Tulip. Neuhart makes it sound as if Charles Eames was too good for cute nicknames. But if Eero didn’t mind, why should Charles? I didn’t feel like I got an answer.

Personally

Neuhart also manages, from the introduction on, to make both Charles and Ray sound like real pills.

Unlike the Eames Office exhibitions, both permanent and temporary, many

of which have been dismantled, destroyed or retired from view, and the films,

many of which are dated in their appeal [debatable] or were related to specific

projects — making them interesting mainly as historical documents — the furniture

is tangible and it has proven, over time, both its commercial and aesthetic value.

There is a lot of it; much of it is still produced and sold and in daily use in homes,

offices and other institutions around the world. If this assessment is accurate, it

is ironic that the furniture is the aspect of the Eames Office work in which Charles

came to be the least interested and absorbed as the years passed.

Wait a minute: this is an 800-page book about a topic in which its chief designer was not interested? Neuhart repeats this claim, that Charles was not interested in the furniture, many times, based on her interviews with Eames Office employees including Don Albinson. I found it a little hard to believe, given that the office produced new furniture designs from the mid-1940s through 1978. It also casts a pall over the proceedings: if Charles wasn’t interested after the 1950s, why should we be? Was all the best furniture work in that first decade, the rest coasting? It seems a question worth asking, answering and perhaps editing accordingly. Neuhart’s agenda seems to be to credit the others in the office with the design and development of what we have come to call Eames furniture. The expansion of credit for midcentury design is certainly a fertile topic (see Metropolis on Irving Harper and the Nelson office, for example). But Neuhart seems determined to take all credit from Charles and particularly Ray, whom she variously describes as inarticulate, procrastinatory and checked-out.

The real designers, in her view, were Harry Bertoia for his work on the plywood and wire chairs, and subsequently Don Albinson. In a 1972 oral history on file at the Archives of American Art, Bertoia acknowledges some bitterness over credit for those plywood experiments. I do not doubt the extensive contributions of others than Eames — from the 1940 MoMA competition on, a supporting cast of future stars worked on all Eames and Saarinen projects — and that they were more hands-on than the bosses. We have to stop believing in the lone genius, molding wood in his Neutra-designed apartment. But that doesn’t mean that Charles is not the author of the chairs. Architects don’t build their own houses, or even their own models. The Eames Office built thousands of furniture models. Picking the right one, the one that looks and feels right, is an act of design. The makers of the 100 others should be credited, but authorship continues to be messy.

A page from a Playboy magazine article featuring Eames, Nelson and Saarinen furniture. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 20100

Design critic Ralph Caplan, who wrote an essay for the catalog of the 1976 exhibition Connections: The Work of Charles and Ray Eames curated by Marilyn and John Neuhart, and worked with Eames and for Herman Miller after the period of greatest furniture foment, told me Eames seemed to have “uncanny creative control.” Unlike Nelson, whose office produced products of wildly varying style and form, I would argue that there is an Eamesian thread. Caplan did say that Charles Eames always spoke of the office as “we,” but he was never sure if the we was royal, Charles and Ray, or the whole staff.

The other problem with Neuhart’s agenda is that much of her information comes from first-person conversations and interviews conducted by the Neuharts over a period of more than 20 years. These interviews are not in an archive. So her history, while first-person, is uncheckable and lightly footnoted as well, though the most extensive interviews seem to have been with Norman Bruns and Albinson. Chapters on Saarinen and Gregory Ain don’t reference recent monographs. This book looks encyclopedic, but is not really up to the academic standards Neuhart dismisses.

The content that has already gotten the most play is Neuhart’s takedown of Ray Eames and her presumption to contribution to the story of Eames furniture.

Ray was never capable of dealing with anything in a rational, step-by-logical-step

fashion. She was often determinedly irrational, arbitrary, petulant and by turns,

childlike and childish. She was also willfully eccentric, intensely undemocratic,

and she made her own rules for herself and for everyone around her. It was

almost impossible for her to make a simple declarative sentence; she spoke in

short bursts of words that came tumbling out with squeaks interspersed with

exclamations and shrieks.

This sounds just plain mean, and out of place in an industrial design history. Even if Neuhart’s claim were true, the tone is one of character assassination. Daniel Ostroff, who is preparing a book of the Eameses writings and interviews, says Charles mentioned Ray as a collaborator from the earliest days of his practice, and quotes Eames Office employees on her contributions to counter the negative quotations collected by Neuhart. Her contributions to the furniture (but for the Eames Wooden Stools) may have been advisory and intangible, but she is credited, for example, as co-director, co-writer and co-producer on many of the Eames films.

Caplan is cited in the introduction as someone who doubted Ray Eames’s contribution. I spoke to Caplan in January, and he said he can’t imagine ever having said Ray Eames was not a major participant in the work, though her contribution was hard to quantify in later years. She did not share what had become Charles's intense interest in mathematics and was not prepared to follow his concern with the development and potential of computers, expressed in films and in exhibitions for IBM. Caplan read Neuhart’s description of Ray’s character and agreed that she could be childlike and had trouble making decisions — but found those traits to be as charming as they could be irritating: "They were intrinsic to Ray's personality; she was funny and lovable." They also were related to her overall attention to the smaller things. She did not draw, but she did understand color and paint and was a sculptor. She told him once that she considered Eames a name that belonged to all their work; even if she was credited with the walnut stools, weren’t they as much Eames furniture as the lounge chair and the wire base table?

Even the skills of Ray’s Neuhart does begrudgingly acknowledge, don’t sound so minor to us today. She contributed to the redesign and reinstallation of the Herman Miller showroom in Los Angeles. She acted as hostess for the Eames Office, arranging flowers and meals there and at the Eames House. She made herself a new boutonniere, a combination of ribbon and flower and brooch each day (a catalog of these would make an excellent blog).

She was consumed by the details — her lovely and unique table settings

with their mix of candles and flowers, the variety of patterns and forms in

her favorite blue and white china (Royal Copenhagen’s “Blue Danube”),

and the Lilliputian scale of the food cooked and presented by either of the

Eameses’ two cook-housekeepers (one at home and one at the office),

were highly individual and enhanced every meal she presented.

Today we would have called Ray Eames a stylist, and she might have out-earned Charles. Neuhart’s low estimation of these skills of arrangement and presentation seems at first a feminist reaction to the decorative sphere, and affront at Ray’s presumption to participation in design. But later in the book Neuhart approvingly describes the skills of Susan Girard, wife of Alexander, in very similar terms — managing the office and home, maintaining their flair and style. (Neuhart worked with Girard, designing the famous stuffed dolls sold at Textiles + Objects, among other projects, and is reportedly planning a similar encyclopedic volume on his work). Susan, however, never claimed co-credit, and “had excellent judgement and acted as a sounding board and critic as the work progressed.” No shrieking, I guess.

Finally

Of all the stop-start narratives I read in the book, the one that really grabbed me was the story of the fiberglass shell chair. I grew up with a pair of LCWs, which I thought were the ugliest things in the world until I was a teenager. But the Fiberglass Arm Chair is hard to hate. That’s why people put the rocker version in their nurseries, that’s why it keeps getting recolored (originally only in greige, elephant-hide gray and parchment — Charles needed someone to add a little color to his world). To us the fiberglass shells now look as natural as Windsor or Thonet chairs, inevitable mergers of material, method and a certain animal bulk. Neuhart’s up-close narrative returns us to the arbitrary nature of the chair’s form and includes some great estranging photos of the chair’s wooly stage. She’s right that this furniture endures, but she can’t tell us why. (There is a book about just this chair, which I have not seen, written by Ostroff with an introduction by Eames Demetrios.)

Molded fiberglass armchair. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 2010

Stevens Trusonic Speaker. Image credit: From The Story of Eames Furniture, Copyright Gestalten 2010

The Eames Life-Time Chair. Image credit: © 2010 Eames Office LLC, from the Collections of the Library of Congress