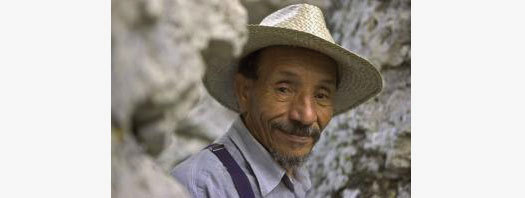

Something special is happening in France. A 73 year old Algerian-born farmer, philosopher and environmentalist is beginning to impact not just on the electoral process, but the culture of this resolutely human-centered, nature-dominating country.

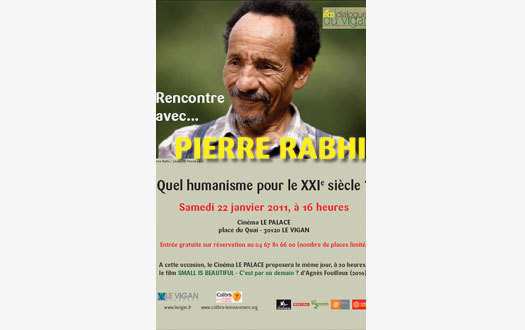

Last weekend I joined the second of two sell-out crowds in Le Vigan, a small Cevennes town near where I live, to hear Pierre Rabhi, founder of the “International Movement for Earth and Humanism.”

Rabhi's first talked about “the deep fear that is in us all” as the impacts of modernity are felt, but soon went on to describe such concepts as “happy sobriety,” a “de-growth economy” and “agro-ecology.”

These terms may sound hippy-dippy — but this was a culturally-mixed and decidedly unsentimental crowd. They came in large numbers because here, for perhaps the first time, is a public figure who makes an economy of moderation and balance sound attractive and do-able, rather than depressing and unrealistic. Rabhi even made a joke about cutting down oak trees.

Pierre Rabhi (I'm quoting Wikipedia here) was born into a Muslim family an an oasis in southern Algeria, in 1938. His mother died when he was four years old. His father, a blacksmith, musician and poet, was forced by economic circumstances to close his workshop and work in the mines. The father persuaded a French couple to raise Pierre; his childhood thereafter was shared between France and Algeria, and the Catholic and Muslim worlds, until he was 14.

He chose to convert to Christianity when he was sixteen and completed two years of secondary education, but had to leave college because his family were unable to cover the costs. When the Algerian War broke out in 1954, Rabhi was rejected by his father for having converted to Christianity and by his adoptive father following a dispute. He decided to settle in Paris.

In France, Rabhi, with no knowledge of agriculture, moved with his new family to the country; this was well before the French 'neo-rural' movement of the late 1960s. In 1963, after three years working as an agricultural worker, he became a goat farmer. Appalled by the impacts of industrialised agriculture on ecosystems he had witnessed in the Sahara and around him in France, he developed the practice of ecological agriculture.

“I am often called a philosopher,” Rabhi told an interviewer, "but you must know that I came to ecology through farming.” On his farm in the Cevennes of Ardèche, he has lived for 13 years without electricity, water or modern technology. Through this experiment he has discovered that “man has created a radical break between activities that enable them to feed themselves and essential principles of nature. The little plot of land that I cultivated in Ardèche widened my horizons and enabled me to connect with time and space all around the world.”

Rabhi wondered whether his experiment was transmissible. In 1985, he set up an agro-ecology training centre; and in 1988 he also founded an International forum for the sharing of knowledge about applied to agricultural practices, CIEPAD. "I realized that the South had been trapped by modernity, that it was connected through chemical fertilizers and pesticides” he explained; “the South is especially affected by ecological disasters, by the disappearance of animal and vegetal biodiversity, by desertification.” He has since launched oversees development programmes in Morocco, Palestine, Algeria, Tunisiea, Senegal, Togo, Benin, Mauritaniea, Poland and the Ukraine.

Rabhi's work had a big influence on the emerging anti-globaization movement. He is a member of the board of editors of the French monthly La Décroissance — “De-Growth.”

Kokopelli works to protect biodiversity in the production and distribution of organically and biodynamically grown seeds and for the regeneration of the fertility of cultivated soils.

In 2009, Rabhi founded Terre et Humanisme (Colibris), an “International movement for earth and humanism.” Since then, more than two million people have been involved in Colibris' place-based projects and encounters and more than 100 groups have been launched. These aim in different ways to create ecological and socially ways to organize daily life. A plethora of initiatives includes AMAPs (community supported agriculture schemes); apiaries, ecological building workshops, shared gardens and other educational activities.

(This film, as an example, is about the citizens of Rennes developing their own climate plan. It's not dissimilar to the Energy Decent Action Plans being pioneered by the Transition Towns movement.)

With presidential elections due in France next year, 2012, Rabhi has now launched a “campaign without a candidate” in which last weekend's meetings in Le Vigan were an early step. The idea is to demonstrate to French citizens that an alternative to politics-as-usual is possible. Describing the campaign as an “insurrection of the conscience”, Rabhi explains that the campaign is not about reforming present society with its “banal consumption” and “pervasive fear.” Rather, it is about accelerating the emergence of its replacement.

The Colibris campaign is based on a Charter for the Earth and Humanity. The Charter first outlines five existential challenges: “The Disaster of Chemical Agriculture,” “Humanity has Failed Humanism,” “Disconnection between Humans and Nature,” “The Myth of Unlimited Growth,” “The Powerless at the Mercy of Money.” It then proposes six responses to these challenges: “Embody Utopia,” “Happy Sobriety,” “Femininity at the Heart of Change,” “Agroecology as Indispenable Alternative,” “Earth and Humanism are One,” “Re-localization of the Economy,” “Another Education.”

This kind of language may strike some English readers as portentous; (This writer's clunky translation won't have helped.) But in Le Vigan, last weekend, the atmosphere was the opposite of sanctimonious. On the contrary: What's special about the social movement Rabhi is catalysing is that it's serious and determined — but also light.

Asked whether he believed in life after death, the non-candidate for President of France replied that “I'm more preoccupied with life before death... but in the long run, I am compost.”