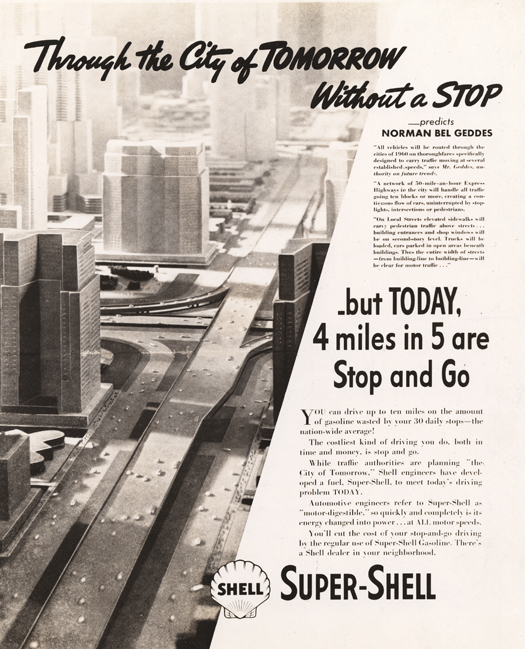

Norman Bel Geddes, "Through the City of Tomorrow without a Stop," advertisement for Shell Oil advertising campaign, ca. 1932-1938

Image courtesy of the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation / Harry Ransom Center

Late last week I had the pleasure of attending the tenth biennial Flair Symposium at the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin. The theme this year was “Visions of the Future,” in conjunction with the exhibition “I Have Seen the Future: Norman Bel Geddes Designs America,” curated by Donald Albrecht. One of the pleasures of the symposium, also one of the pleasures of Geddes’s career, was its diversity. How many ways can you talk about the future? The first panel of the day featured Jen Gunnels, the theater critic for the New York Review of Science Fiction, John Crowley, a science fiction writer, and the director of the University of Houston’s Future Studies program, Peter Bishop. Bishop had my quotable quote of the symposium: “The most important thing in predicting the future is not to get it right, but to present a set of plausible futures. Looking for the right future is a futile exercise. Thinking about the future is like jogging – you end up where you started but in better condition.”

The next panel discussed future architectures, from Geddes’s 1939 Futurama to Googie to the perfectly and scientifically planned postwar house. My panel, on “Marketing the Future,” was last, and covered the role of the department store and color associations as trendsetters. I spoke about the domestication of the future, with a set of midcentury husband-and-wife store owners putting themselves on display to show how easy modern life could be. Sitting in the hall, I realized the focus on future families could be extended out from the glassy shops and glassy houses to a broader swath of pop culture. What were the Jetsons, after all, but another way of making the future seem mom and pop? (Matt Novak has been recapping every episode of that show at his Paleofuture blog.)

Vandamm Studio, "Travel Smartly in Tweed" window display for Franklin Simon, ca. 1929

Image courtesy of the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation / Harry Ransom Center

Geddes, however, would not have been as sanguine as Bishop about creating a set of plausibilites. The last wall of the encyclopedic exhibition features an article of future predictions Geddes wrote in 1930. So there could be no mistake, he went back several years later and checked off what had become true. On building: “Synthetic materials will replace the products of Nature in buildings.” “The garage will be part of the house and will be placed on the street front.” “Neon tubes will replace the incandescent lamp.” “The home will become so mechanized that handwork will be reduced to a minimum.” On communications: “Courses and lectures will be broadcast by television from key cities to hundreds of rural branches.” On design: “Women’s dresses will be shorter; women’s dresses will be longer; women’s dresses will be shorter; then, women’s dresses will be longer.” “Utilitarian objects will be as beautiful as what we call today ‘works of art.’”

I would be struck by his range if I had not just seen the exhibition, which hits all the high spots of industrial design within one man’s oeuvre. There are the utilitarian objects of desire, including a totemic Revere Copper And Brass cocktail shaker (1937) and the bright red Patriot radio (1940-41) that made the Pioneers of American Industrial Design stamps. There are zoomy planes, trains and automobiles. There is the Futurama, the General Motors exhibition at the 1939 World’s Fair seen by 25 million people, which predicted the world of superhighways, high rises and suburban single family homes America had largely become by the 1964 World’s Fair, when it was reprised. But there are also odder, more emotional moments.

Francis Bruguière, Divine Comedy Model with Lighting and Figures, 1924

Image courtesy of the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation / Harry Ransom Center

Geddes’s early career as a stage designer, which I always glossed over, turns out to be essential. Even as he rendered his designs in watercolor and ink he understood that they would live on as photographs. He carefully lit, populated and photographed his models, controlling the image of his own work like a director, and often making it look bigger, bolder and more dramatic than the reality. When he turned to shop windows, he lit the merchandise like a star. When it was his sets on display, he paid attention to their cheekbones. A minimalist, stair-crazy set for Hamlet, designed in 1929, makes all of the actors into newel posts. This attention to rendered detail reminded me of some architects today, who speak through rendering, and know that the image of the building is what lingers in the popular imagination – whether or not it looks that way after construction.

At the other end of his career, in the late 1940s, Geddes returned to the idea of the stage with various entertainment architectures, many of them featuring the moving conga lines of cars and viewers that had proven so successful at the Fair. His consumers’ building, pitched to General Motors in 1949, had a curvaceous exterior volume reminiscent of Erich Mendelsohn (then) and Future Systems (now). Inside the multistory structure people moved around the merchandise via ramps, performing a sort of shoppers’ theater for people outside on the street. Copa City in Miami (1948) combined a nightclub, department store and broadcast studio. And there was also work for Ringling Brothers’ circus and a never-built all-weather stadium with a retractable roof for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Where there were people to watch, there was Geddes, finding the theatrical in all the elements of modern urban life.

Prototype case for Emerson Patriot radio, ca. 1940-1941.

Image courtesy of the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation / Harry Ransom Center

I could go on, and I may after I finish reading the Geddes catalog, with essays on Modular and Mobile, Housing, Workplaces, Furniture and Graphic Design. The exhibition will be at the Ransom Center through January 6, and then make its way north to the Museum of the City of New York. In related news, “Designing Tomorrow: America’s World’s Fairs of the 1930s,” which I wrote about here, will open at MCNY on December 5. More futures, more exercise.