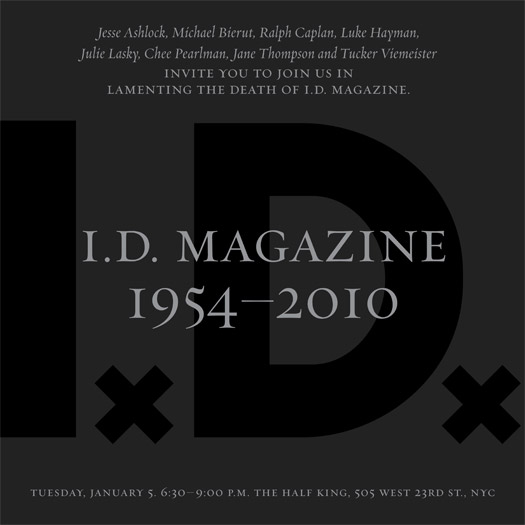

Invitation to I.D.'s wake, January 5, 2010. Designer: Luke Hayman; typeface: Requiem by Jonathan Hoefler.

Late in 2002, a publisher asked me to consider editing a beloved design magazine that had fallen on hard times. Three years before, the magazine had been relocated from New York, where it resided for decades, to its parent company’s home in Cincinnati. The decision proved disastrous. Supervised by eager yet inexperienced editors removed from the metropolitan swim of design — the unceasing flow of product introductions, PR lunches, trade shows, hard-hat building tours and studio visits — the magazine had lost its focus and much of its audience and was consequently hemorrhaging readers and ad dollars.

“So, will you think about taking over I.D.?” the publisher asked.

“Absolutely not,” I said.

I knew all about this bungled Ohioan adventure from a previous I.D. editor, who happened to be a friend of mine. He had recounted being hired on the eve of the magazine’s move, though no one had told him about it. Instead, his first day on the job was spent wandering around empty offices. (Much of the staff had been dismissed the previous day, and he joked that their leave-taking was so abrupt the place was littered with half-eaten sandwiches.) As I.D.’s sole editor in New York working alongside the ad salespeople, my friend spent the next year trying to manage staff in another state whom, he complained, he had not been allowed to hire and who had never heard of Philip Johnson. He phoned me with regular bulletins of management atrocities, culminating in the rerouting of his mail to the Cincinnati office; he was actually barred from opening it. At the year’s end, my friend’s contract expired, and he left.

“No way,” I reiterated.

Besides, I was still smarting from my own recent experience of corporate brutality. In June 2001, the legendary magazine Interiors shut down because its parent company had acquired an interior design periodical that ran on a fraction of its budget. Interiors had been founded in 1888. I was its last editor. I took a chunk of my risible severance package and bought a David Wojnarowicz photograph of buffalo being driven off a cliff. Less than three months later, the World Trade Towers were blown up. I decided maybe I should hunker down in my Brooklyn apartment for a while and spent the next 18 months in my pajamas.

“Really, thanks,” I told I.D.’s publisher. “But I don’t think I can work for those people.”

“But the people have all changed,” the publisher, who was himself a new arrival, said. “The company is sorry about the mess that was made, and everyone responsible for that bad decision is gone now.”

A bottom-line-oriented company in the age of Bush had acknowledged wrongdoing and expressed regret? I looked into the sympathetic eyes of this kind man and thought about my COBRA benefits, which would soon be coming to an end. I took the job. “Don’t do what I did,” my friend the former editor said when he heard the news. “Don’t call your bosses liars. Especially not to their faces.” Six months later, the nice publisher who hired me was sent packing.

I stayed at I.D. for the next six years. Over that time, the parent company, which had been owned by a private equity firm based in Providence, Rhode Island, was sold to a private equity firm based in Boston. The new backers introduced a new CEO (an art-loving guy who had written his undergraduate thesis on the symbolism of bread in the work of James Joyce) and replaced him a year later with someone they judged more effective at cutting costs (a sports-loving guy who used a lot of basketball metaphors). For the next six years, I reported to a succession of nine supervisors, including recent publishers of magazines about horticulture and scuba diving. The blogosphere was born and the global economy fell to pieces. And yet nothing in the corporate zeitgeist shifted an iota. Though the cells were constantly regenerated, the parent entity remained exactly the same. Like hundreds of American businesses, it was obsessed with short-term profitability, the future be damned. And no one who had any serious power over I.D. seemed to understand anything about design.

On the contrary, the thread connecting almost all of the disparate players I reported to was their insistence that they couldn’t tell the difference between I.D. and its sister magazines Print and How. As the revolving door turned, I would march into executive offices carrying armloads of back issues and tell each new boss the story of I.D., from its origins in 1954 as Industrial Design to the present day. I explained that the “I” in I.D. stood for “international” but also, tacitly, “interdisciplinary” and “innovative.” I discoursed on the recent convergence of design practices that in my view made it appropriate to bundle products, buildings and graphics within the covers of a single magazine. I suggested that although I.D.’s audience was divided among different kinds of designers, which reduced its appeal to advertisers, all of those readers were visually acute and shared an interest in smart ideas. Perhaps there was a way to think about innovation as an advertising category? I showed evidence of I.D.’s global stature and urged the establishment of a strong web presence that could serve as a window on the world and open new avenues for profit (not to mention shore up I.D.’s reputation for featuring cutting-edge design). On each occasion, I was politely told that the typical buyer of advertising space lacked the time and intelligence to grasp complicated ideas such as I had just presented. Nor in six years was any notable investment made in a dedicated sales staff, reader research or web development for I.D.

Imagine going to a hospital and learning from the person holding the scalpel that he really doesn’t see a difference between your hand and your foot; after all, an appendage is an appendage, and a sock can be pulled over any of them. A blogger commenting on Bruce Nussbaum’s post about I.D.’s death wondered whether design thinking had been applied in any attempt to keep the magazine going. Don’t make me laugh. Whereas designers spend their days making astute decisions based on the accumulation of facts, I.D.’s executioners seemed to feel that genuine understanding of their property was too expensive to acquire and finally irrelevant.

In their minds, the suits did away with an antiquated pile of paper that taxed their resources and imaginations. But for those of us who produced and consumed I.D., in same cases for decades, an animate thing was prematurely struck down. Magazines are organic. They take on shapes and personalities that are independent of those who make them, and in this margin of self-sufficiency is something eerily close to life. Magazines are mammalian: warm-blooded, twitchy and dynamic whereas the businesses that buy them to turn a quick profit are cold-blooded reptiles, apt to engage in long bouts of inertia except for an occasional spastic flick of a murderous tongue.

And of course magazines are historical. The internet is a bottomless archive, but it spits information back to us in fragments, and we’re never sure which pieces might disappear forever. A magazine archive unspools to allow us to see aesthetic movements wildly imitated before they’re just as passionately revoked and to watch the youth of our industries mature and grow old and give way to new talents. Would anyone be able to make sense of so unruly a profession as design, with its vague and shifting borders, if it weren’t bound into our journals?

History is hardly respected by a company whose institutional memory is as long as my thumb. Shortly before I left I.D. in early 2009 to work on Design Observer, someone raised the idea of cutting costs by moving the magazine to….Cincinnati. So many corporate employees had turned over in six years that only a few people realized that the gambit had ever been attempted. It was then that I knew I had to go.

Late in 2002, a publisher asked me to consider editing a beloved design magazine that had fallen on hard times. Three years before, the magazine had been relocated from New York, where it resided for decades, to its parent company’s home in Cincinnati. The decision proved disastrous. Supervised by eager yet inexperienced editors removed from the metropolitan swim of design — the unceasing flow of product introductions, PR lunches, trade shows, hard-hat building tours and studio visits — the magazine had lost its focus and much of its audience and was consequently hemorrhaging readers and ad dollars.

“So, will you think about taking over I.D.?” the publisher asked.

“Absolutely not,” I said.

I knew all about this bungled Ohioan adventure from a previous I.D. editor, who happened to be a friend of mine. He had recounted being hired on the eve of the magazine’s move, though no one had told him about it. Instead, his first day on the job was spent wandering around empty offices. (Much of the staff had been dismissed the previous day, and he joked that their leave-taking was so abrupt the place was littered with half-eaten sandwiches.) As I.D.’s sole editor in New York working alongside the ad salespeople, my friend spent the next year trying to manage staff in another state whom, he complained, he had not been allowed to hire and who had never heard of Philip Johnson. He phoned me with regular bulletins of management atrocities, culminating in the rerouting of his mail to the Cincinnati office; he was actually barred from opening it. At the year’s end, my friend’s contract expired, and he left.

“No way,” I reiterated.

Besides, I was still smarting from my own recent experience of corporate brutality. In June 2001, the legendary magazine Interiors shut down because its parent company had acquired an interior design periodical that ran on a fraction of its budget. Interiors had been founded in 1888. I was its last editor. I took a chunk of my risible severance package and bought a David Wojnarowicz photograph of buffalo being driven off a cliff. Less than three months later, the World Trade Towers were blown up. I decided maybe I should hunker down in my Brooklyn apartment for a while and spent the next 18 months in my pajamas.

“Really, thanks,” I told I.D.’s publisher. “But I don’t think I can work for those people.”

“But the people have all changed,” the publisher, who was himself a new arrival, said. “The company is sorry about the mess that was made, and everyone responsible for that bad decision is gone now.”

A bottom-line-oriented company in the age of Bush had acknowledged wrongdoing and expressed regret? I looked into the sympathetic eyes of this kind man and thought about my COBRA benefits, which would soon be coming to an end. I took the job. “Don’t do what I did,” my friend the former editor said when he heard the news. “Don’t call your bosses liars. Especially not to their faces.” Six months later, the nice publisher who hired me was sent packing.

I stayed at I.D. for the next six years. Over that time, the parent company, which had been owned by a private equity firm based in Providence, Rhode Island, was sold to a private equity firm based in Boston. The new backers introduced a new CEO (an art-loving guy who had written his undergraduate thesis on the symbolism of bread in the work of James Joyce) and replaced him a year later with someone they judged more effective at cutting costs (a sports-loving guy who used a lot of basketball metaphors). For the next six years, I reported to a succession of nine supervisors, including recent publishers of magazines about horticulture and scuba diving. The blogosphere was born and the global economy fell to pieces. And yet nothing in the corporate zeitgeist shifted an iota. Though the cells were constantly regenerated, the parent entity remained exactly the same. Like hundreds of American businesses, it was obsessed with short-term profitability, the future be damned. And no one who had any serious power over I.D. seemed to understand anything about design.

On the contrary, the thread connecting almost all of the disparate players I reported to was their insistence that they couldn’t tell the difference between I.D. and its sister magazines Print and How. As the revolving door turned, I would march into executive offices carrying armloads of back issues and tell each new boss the story of I.D., from its origins in 1954 as Industrial Design to the present day. I explained that the “I” in I.D. stood for “international” but also, tacitly, “interdisciplinary” and “innovative.” I discoursed on the recent convergence of design practices that in my view made it appropriate to bundle products, buildings and graphics within the covers of a single magazine. I suggested that although I.D.’s audience was divided among different kinds of designers, which reduced its appeal to advertisers, all of those readers were visually acute and shared an interest in smart ideas. Perhaps there was a way to think about innovation as an advertising category? I showed evidence of I.D.’s global stature and urged the establishment of a strong web presence that could serve as a window on the world and open new avenues for profit (not to mention shore up I.D.’s reputation for featuring cutting-edge design). On each occasion, I was politely told that the typical buyer of advertising space lacked the time and intelligence to grasp complicated ideas such as I had just presented. Nor in six years was any notable investment made in a dedicated sales staff, reader research or web development for I.D.

Imagine going to a hospital and learning from the person holding the scalpel that he really doesn’t see a difference between your hand and your foot; after all, an appendage is an appendage, and a sock can be pulled over any of them. A blogger commenting on Bruce Nussbaum’s post about I.D.’s death wondered whether design thinking had been applied in any attempt to keep the magazine going. Don’t make me laugh. Whereas designers spend their days making astute decisions based on the accumulation of facts, I.D.’s executioners seemed to feel that genuine understanding of their property was too expensive to acquire and finally irrelevant.

In their minds, the suits did away with an antiquated pile of paper that taxed their resources and imaginations. But for those of us who produced and consumed I.D., in same cases for decades, an animate thing was prematurely struck down. Magazines are organic. They take on shapes and personalities that are independent of those who make them, and in this margin of self-sufficiency is something eerily close to life. Magazines are mammalian: warm-blooded, twitchy and dynamic whereas the businesses that buy them to turn a quick profit are cold-blooded reptiles, apt to engage in long bouts of inertia except for an occasional spastic flick of a murderous tongue.

And of course magazines are historical. The internet is a bottomless archive, but it spits information back to us in fragments, and we’re never sure which pieces might disappear forever. A magazine archive unspools to allow us to see aesthetic movements wildly imitated before they’re just as passionately revoked and to watch the youth of our industries mature and grow old and give way to new talents. Would anyone be able to make sense of so unruly a profession as design, with its vague and shifting borders, if it weren’t bound into our journals?

History is hardly respected by a company whose institutional memory is as long as my thumb. Shortly before I left I.D. in early 2009 to work on Design Observer, someone raised the idea of cutting costs by moving the magazine to….Cincinnati. So many corporate employees had turned over in six years that only a few people realized that the gambit had ever been attempted. It was then that I knew I had to go.