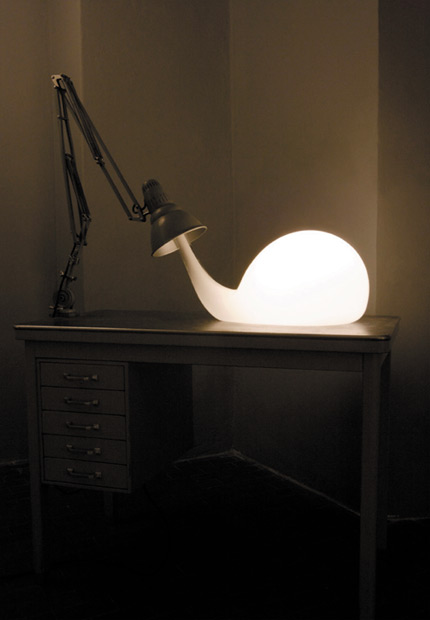

Light Blub by Pieke Bergmann, photo by Studio Design Virus

Essay adapted from "In Praise of Shadows: New European Lighting Design," presented at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, September 19–October 18, 2009. Curated by Jane Withers at the invitation of the European Union National Institutes for Culture (EUNIC), the exhibition demonstrated poetic uses of low-energy light sources and alternative forms of energy as well as commentaries on traditional bulbs and fixtures. The show was installed in the V&A's Jones Galleries featuring European decorative art from the 17th through 19th centuries, which had been closed for renovation. Visitors navigated the dimly illuminated space with flashlights.

The standard GLS or incandescent electric light bulb is such a familiar and enduring icon that it is almost impossible to imagine life without it. The glowing filament is a silent accomplice in our darker hours, magically extending the day into night. Beyond its primary function as a light source, it has also played a powerful part in modern culture — think of the phenomenal legacy of the light bulb as a graphic icon and symbol of ideas. But in September when EU legislation on energy-efficient lighting came into force the conventional bulb started to be phased out and one of modernism’s greatest products has been consigned to the dustbin, or more likely landfill. RIP Edison.

An extraordinary icon, it may be, but it is also extraordinary that a technology from the 1870s should remain pretty much unchanged and unchallenged for more than a century, and its energy inefficiency (over 90 percent is wasted in heat) is indefensible. It is rare that an issue in the design world has such far-reaching implications for us all or gets people quite so overheated.

In the process of working on this exhibition on new European lighting design, I’ve encountered confusion and controversy. There are Save the Bulb campaigns and Ban the Bulb campaigns as well as a litany of "requiems" for the incandescent light bulb. Brilliant German lighting designer Ingo Maurer mischievously presented an "EU condom" at the Milan Furniture Fair, an opaque sheath designed to disguise old-style GLS bulbs as new, low-energy ones.

An aspect of the mounting environmental crisis is that it raises plenty of real-life challenges for designers and makes recent "designer" styling look rather last millennium. There is no doubt that lighting is embarking on a period of massive change. The shift to greater energy efficiency (already legislated to varying degrees in Argentina, Australia, Canada, US and Venezuela) has already proved a catalyst to rapid technological development. In the last decade, lighting has changed dramatically with the introduction of CFLs, LEDs, and now Organic LEDs (OLEDs) and arguably this is only the beginning.

When new technologies emerge there is often a period of uncertainty before the commercial world settles on a way forward. Remember the battle between Betamax and VHS before VHS triumphed only to be overtaken by DVDs?

Historians list 22 inventors of incandescent lamps prior to Thomas Edison’s commercially viable version. Yet despite the pace of technological change, surely debate surrounding lighting and energy should go beyond geeky discussions about technologies and bulbs? It should be a chance to explore new thinking not just about lighting and sustainability but about the quality of light, and to challenge the modern obsession with brightness that has held sway for over a century.

The exhibition I curated, "In Praise of Shadows," at the Victoria and Albert Museum this fall, emerged in response to the EU’s legislation. It aimed to add spark to the lighting and energy debate by bringing together projects by 20 or so European designers who imaginatively explore not only the potential of low-energy lighting and alternative sources but also the qualities of light and the way we think about light and darkness. Appropriately it squatted in the Jones Galleries of European Decorative Art, which closed for refurbishment during the summer. For the exhibition, visitors went behind a hoarding to explore a semi-darkened room where lights were mysterious interlopers contrasting eerily with ornate works still on display.

As well as raising some of the critical issues about energy, the exhibition was about engaging with the human dimension that tends to be forgotten in the energy debate. Works were selected around three themes. The first is poetics of light, and illustrates the freedom low-energy light sources can bring to lighting design. One of my favorite pieces is Fragile Futures by Dutch designer Drift. A magical hybrid of nature and technology, the electric circuit seems to grow organically over a wall, sprouting dandelion seed heads along the way, each illuminated by an LED to create a twinkling constellation.

The second grouping is concerned with lighting spaces but also how we interact with light and its physiological effects. You may be familiar with the essay from which the exhibition title was borrowed. Written by Japanese novelist Jun’ichiro Tanizaki in 1933, it characterized the bright lights of Westernization as driving away the shadows of richness and depth of Japanese culture. Haven’t we similarly had enough of the over-lit glare of hospitals and offices where you feel fried by the end of the day? Or the bland and disorientating uniformity of airports and supermarkets? Swedish lighting manufacturer Magnus Wästberg is fond of quoting a premonition of the Swedish writer August Strindberg (1849–1912): "Electric light will make people work themselves to death." According to RCA research associate Claudia Dutson, "The commercial attitude towards lighting and environmental ideology are in conflict. 'Brighter is better' is the motto; offices worldwide are lit-up throughout the night conveying a strong message that 'this company is switched-on' and 'at work' even when the buildings are empty of workers. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that high levels of light, the wrong colors of light and the separation from natural rhythms of daylight in the office have a negative impact on workers’ health."

Wästberg believes there is good reason this has come about. "In our industry it’s all too easy to talk about the technology and other issues just get ignored," he says. "It’s clear that people are very angry about the discontinuation of the incandescent bulb and this shows the emotional significance of lighting. But when it comes to lighting, very little of the aesthetic or emotional side is taken into account."

The exhibition’s third key theme is powering and alternative energy sources, and again experimental thinking is making rapid progress. There are increasing numbers of lights that use solar and wind power on the horizon and arguably this is the future. iGuzzini and Ropatec have collaborated on a Wind and Light project — planned to launch at the G8 summit on Sardinia — that converts wind power into light. Experimental designer Demakersvan has a more elegant version of a similar idea in the exhibition. Programs such as the World Bank’s Lighting Africa project are helping bring low-cost, low-maintenance solutions for lighting areas off the national grid to fruition. In the exhibition, we have Loop’s magical Sonumbra: a giant parasol made from architectural textile embedded with solar cells and electroluminescent wires. By day it serves as a sunshade and by night it gives off the light it absorbs.

The show ends on a cautionary note about energy waste and light pollution. French eco activists Clan du Néon protest against the absurd energy waste of illuminated advertising signs by simply turning them off and then posting films of their actions on the internet. The most amusing shows three figures in fluorescent wigs running down rue de other’s shoulders to switch off famous shop signs using external switches intended for emergency use by the fire brigade. It’s both silly and deeply important. Why do we sanction bright lights of advertising pointlessly pouring energy into our over illuminated skies?

The movement has already spread across France and into Holland. As much as new light technologies, it is thinking like this about how we use energy and how we want our lives illuminated that can help change habits and point the way to a sustainable future.

The standard GLS or incandescent electric light bulb is such a familiar and enduring icon that it is almost impossible to imagine life without it. The glowing filament is a silent accomplice in our darker hours, magically extending the day into night. Beyond its primary function as a light source, it has also played a powerful part in modern culture — think of the phenomenal legacy of the light bulb as a graphic icon and symbol of ideas. But in September when EU legislation on energy-efficient lighting came into force the conventional bulb started to be phased out and one of modernism’s greatest products has been consigned to the dustbin, or more likely landfill. RIP Edison.

An extraordinary icon, it may be, but it is also extraordinary that a technology from the 1870s should remain pretty much unchanged and unchallenged for more than a century, and its energy inefficiency (over 90 percent is wasted in heat) is indefensible. It is rare that an issue in the design world has such far-reaching implications for us all or gets people quite so overheated.

In the process of working on this exhibition on new European lighting design, I’ve encountered confusion and controversy. There are Save the Bulb campaigns and Ban the Bulb campaigns as well as a litany of "requiems" for the incandescent light bulb. Brilliant German lighting designer Ingo Maurer mischievously presented an "EU condom" at the Milan Furniture Fair, an opaque sheath designed to disguise old-style GLS bulbs as new, low-energy ones.

An aspect of the mounting environmental crisis is that it raises plenty of real-life challenges for designers and makes recent "designer" styling look rather last millennium. There is no doubt that lighting is embarking on a period of massive change. The shift to greater energy efficiency (already legislated to varying degrees in Argentina, Australia, Canada, US and Venezuela) has already proved a catalyst to rapid technological development. In the last decade, lighting has changed dramatically with the introduction of CFLs, LEDs, and now Organic LEDs (OLEDs) and arguably this is only the beginning.

When new technologies emerge there is often a period of uncertainty before the commercial world settles on a way forward. Remember the battle between Betamax and VHS before VHS triumphed only to be overtaken by DVDs?

Historians list 22 inventors of incandescent lamps prior to Thomas Edison’s commercially viable version. Yet despite the pace of technological change, surely debate surrounding lighting and energy should go beyond geeky discussions about technologies and bulbs? It should be a chance to explore new thinking not just about lighting and sustainability but about the quality of light, and to challenge the modern obsession with brightness that has held sway for over a century.

The exhibition I curated, "In Praise of Shadows," at the Victoria and Albert Museum this fall, emerged in response to the EU’s legislation. It aimed to add spark to the lighting and energy debate by bringing together projects by 20 or so European designers who imaginatively explore not only the potential of low-energy lighting and alternative sources but also the qualities of light and the way we think about light and darkness. Appropriately it squatted in the Jones Galleries of European Decorative Art, which closed for refurbishment during the summer. For the exhibition, visitors went behind a hoarding to explore a semi-darkened room where lights were mysterious interlopers contrasting eerily with ornate works still on display.

As well as raising some of the critical issues about energy, the exhibition was about engaging with the human dimension that tends to be forgotten in the energy debate. Works were selected around three themes. The first is poetics of light, and illustrates the freedom low-energy light sources can bring to lighting design. One of my favorite pieces is Fragile Futures by Dutch designer Drift. A magical hybrid of nature and technology, the electric circuit seems to grow organically over a wall, sprouting dandelion seed heads along the way, each illuminated by an LED to create a twinkling constellation.

The second grouping is concerned with lighting spaces but also how we interact with light and its physiological effects. You may be familiar with the essay from which the exhibition title was borrowed. Written by Japanese novelist Jun’ichiro Tanizaki in 1933, it characterized the bright lights of Westernization as driving away the shadows of richness and depth of Japanese culture. Haven’t we similarly had enough of the over-lit glare of hospitals and offices where you feel fried by the end of the day? Or the bland and disorientating uniformity of airports and supermarkets? Swedish lighting manufacturer Magnus Wästberg is fond of quoting a premonition of the Swedish writer August Strindberg (1849–1912): "Electric light will make people work themselves to death." According to RCA research associate Claudia Dutson, "The commercial attitude towards lighting and environmental ideology are in conflict. 'Brighter is better' is the motto; offices worldwide are lit-up throughout the night conveying a strong message that 'this company is switched-on' and 'at work' even when the buildings are empty of workers. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that high levels of light, the wrong colors of light and the separation from natural rhythms of daylight in the office have a negative impact on workers’ health."

Wästberg believes there is good reason this has come about. "In our industry it’s all too easy to talk about the technology and other issues just get ignored," he says. "It’s clear that people are very angry about the discontinuation of the incandescent bulb and this shows the emotional significance of lighting. But when it comes to lighting, very little of the aesthetic or emotional side is taken into account."

The exhibition’s third key theme is powering and alternative energy sources, and again experimental thinking is making rapid progress. There are increasing numbers of lights that use solar and wind power on the horizon and arguably this is the future. iGuzzini and Ropatec have collaborated on a Wind and Light project — planned to launch at the G8 summit on Sardinia — that converts wind power into light. Experimental designer Demakersvan has a more elegant version of a similar idea in the exhibition. Programs such as the World Bank’s Lighting Africa project are helping bring low-cost, low-maintenance solutions for lighting areas off the national grid to fruition. In the exhibition, we have Loop’s magical Sonumbra: a giant parasol made from architectural textile embedded with solar cells and electroluminescent wires. By day it serves as a sunshade and by night it gives off the light it absorbs.

The show ends on a cautionary note about energy waste and light pollution. French eco activists Clan du Néon protest against the absurd energy waste of illuminated advertising signs by simply turning them off and then posting films of their actions on the internet. The most amusing shows three figures in fluorescent wigs running down rue de other’s shoulders to switch off famous shop signs using external switches intended for emergency use by the fire brigade. It’s both silly and deeply important. Why do we sanction bright lights of advertising pointlessly pouring energy into our over illuminated skies?

The movement has already spread across France and into Holland. As much as new light technologies, it is thinking like this about how we use energy and how we want our lives illuminated that can help change habits and point the way to a sustainable future.