An illustration by Heinrich Lefler for Die Bücher der Chronika der drei Schwestern, 1900

The modern and experimental visions found in Viennese Jugendstil book illustrations — are notable for their suggestive powers, intensity and independence. Recently on view at the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna was Jugendschatz und Wunderscherlein, an exhibition curated by Friedrich C. Heller. The collection when looked at as a whole, tells not only the singular narrative of each book, but the over-arching story of Viennese turn-of-the-century politics, education and art.

Turn-of-the-century Vienna was a magical, infectious brew. Take any city tourist brochure, and names from Vienna’s years as an apogee of art and culture spill out: Klimt, Freud, Schoenberg, Wittgenstein, Loos, the list goes on. In these moments, on the cusp of Modernism, the future still looked bright. The Gründerzeit had remade the city into one of Europe’s most imposing capitals. The bourgeois middle class had taken firm root in society. The extreme right-wing and anti-Semitic forces — though quietly fomenting — would lie dormant a few years longer, leaving the intelligentsia and creatives to indulge in their artistic monomania, uninterrupted. A schoolboy in those days, Austrian writer Stefan Zweig recalled in his memoir, The World of Yesterday, “We had eyes only for books and pictures… The city was aroused at the elections, and we went to the libraries. The masses rose, and we wrote and discussed poetry. We did not see the fiery signs on the wall, and like King Belshazzar of old we feasted without care on the precious dishes of art, not looking anxiously into the future.”

Viennese children’s book illustrations at the time were no exception. They flaunted the same overripe aestheticism, as can be seen in Heinrich Lefler’s illustrations in Die Bücher der Chronika der drei Schwestern (Book of Chronicles of the Three Sisters), 1900, whose rampant geometric patterning and insane detailing heralded the arrival of modern book art in Vienna. Lefler’s finest work and no less ornate Schiller-Festgabe der Stadt Wien (Schiller Festschrift of the City of Vienna) was printed and distributed to schoolchildren in 1905 — in bulk and free of charge — on the centenary of the death of the German poet Friedrich Schiller. Other examples were particularly striking because they weren’t only directed to children. Leading artists like Koloman Moser designed children’s books while using them as prototypes for their own work, while intellectuals Otto Neurath and Ernst Gombrich also contributed to the genre — the former with his pictogram innovations, the latter with easier-to-digest versions of his theoretical writings.

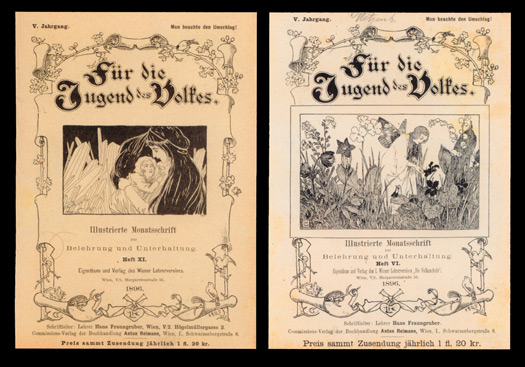

But Viennese children’s books hadn’t always been so decadent, nor city officials so benevolent. Only as recently as 1883 had a child labor law mandated that children rest at least one day a week from their 11-hour-long factory shifts. Soon after, Swedish pedagogue and feminist Ellen Key proclaimed the start of the Century of the Child, and it was in this spirit that a lifelong involvement with art was seen as essential to children's development. Viennese educators inaugurated the Kunsterziehungsbewegung (art education movement), a direction in art pedagogy that was closely tied to the Jugendschritftenbewegung, or youth magazine movement. Between 1897 and 1902, the Austrian Ministry of Education commissioned 33 contemporary artists to produce Bilderbogen für Schule und Haus (Picture Sheets for School and House), inexpensive teaching materials. Magazines such as Für die Jugend des Volkes (For the Youth of the Nation), 1892-1898, targeted children of poor families and were accompanied by remarkable illustrations from artists Koloman Moser, Leo Kainradl and Alexander Pock, the immediate forerunners of the Vienna Secessionists who rebelled against the era’s stale codes of academic art. Art, these young upstarts proclaimed, should be a way of life.

What began as a pedagogical commitment to children and a brighter future became eclipsed by the refusal to face a new and much-changed world. Against the books’ conservative and backwards-looking contents, the emphasis on style and form felt jarring. In his memoir, Stefan Zweig noted that “such overvaluation of the aesthetic, carried to the point of absurdity, could only exist at the expense of the normal interests of our age.” Writer Karl Kraus went even further, condemning the focus on aesthetics as “corrosive, oppressive and immoral.” If that sounds extreme, consider that when Austrian Emperor Franz Josef I died in 1916, the education ministry designed and printed thousands of copies of an extravagant commemorative book, Kaiser Franz Josef I, Ein Erinnerungsbuch (Emperor Franz Josef I: A Memoir), as a gift for schoolchildren. No matter that the monarchy had long lost its ability to rule and Austria was on the verge of dissolution. Worse even was that the intended schoolchildren were literally starving to death; the shortages caused by the Allied blockade resulted in widespread malnutrition, wiping out as much as 30 percent of the population.

It was only after the First World War and the founding of the new Austrian republic that new opportunities for illustration began to present themselves. The Social Democrats implemented their program of reform teaching in 1918, and Socialism — known as the era of Red Vienna — had begun to set in. One of the most popular youth magazines during this time was the Jugendrotkreuz Zeitschrift (Magazine for the Red Cross Youth), illustrated by the well-known artist Franz Cizek, which was committed to the goals of tolerance, peace and moral rebuilding of young people after the war.

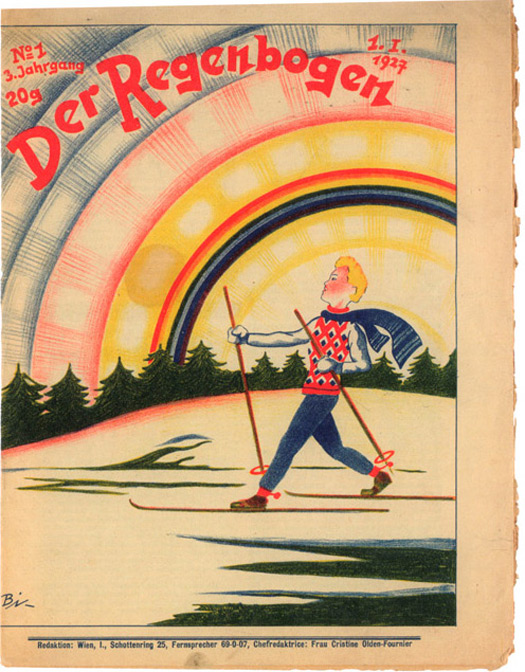

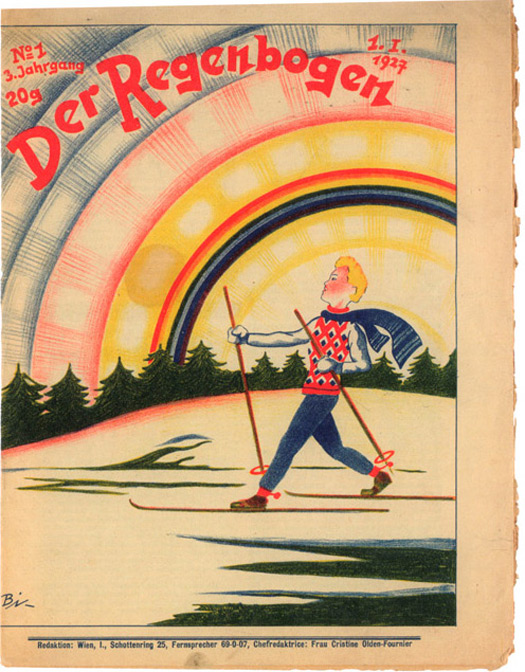

Books like Hoch Die Republik (Exalt the Republic), 1918, were modern and optimistic, with clean lines once again representing hope for a better future. The book was intended as a gift for Viennese primary schoolchildren, but as a precursor of hardships to come, was eventually banned. The Ministry of Education — later dominated by the conservative Christian-Social Party — criticized the depiction of certain social democratic ideals. And many weekly children's publications — including Der Regenbogen, Wochenschrift für Kinder (The Rainbow: Children's Weekly), 1924-27, and Der Weg ins Leben (The Path to Life), 1924, met with the same fate. The latter’s covers exemplified “Viennese Kineticism” with streaks of chalky black, vibrating with energy and spirit. Inside, the texts pondered rational enlightenment, pacifism and an activist view of life.

More acceptable in a political sense were books like Buch der Arbeit (Book of Work), 1922, where labor was idealized through factory scenes of puffing smokestacks, with workers reduced to ant-like miniatures in the foreground. Published by the Social Democrats and printed from 1923 to 1934, the Constructivist-influenced Kinderland, die Zeitung der Osterre Arbeiterkinder und Bauernkinder (Children's Land: The Newspaper for Austrian Workers' Children and Farm Children) was more typographically progressive and more widely read.

Around this time, as Austria’s political situation steadily worsened, so finally did children’s pictorial worlds. Curator Friedrich C. Heller links the waning artistic quality to the rise in popularity of “cute modes of representation” as seen in the saccharine Kind und Zeit (Child and Time), 1927. Other examples were books for city children that aestheticized country and peasant life.

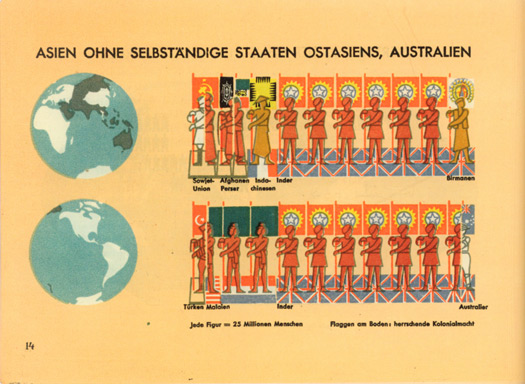

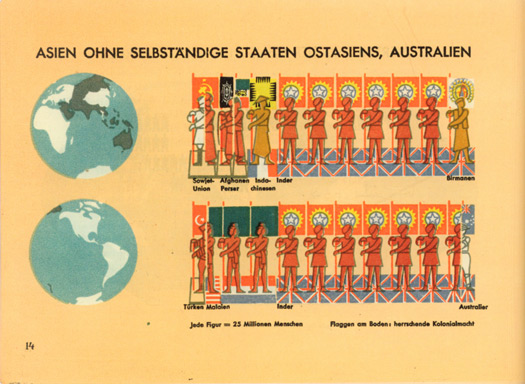

Nevertheless, two remarkable books would still be published over the next decade. The first was Otto Neurath’s Die Bunte Welt (The Colorful World), 1929, a pioneering example of graphic design and visual communication. Neurath had attempted to develop a universal visual language which is reflected in the book’s tables, such as "The Population of Asia, not including East Asia and Australia," and "Followers of the World’s Major Religions." Here, Neurath illustrates population figures with simplified composites of the then-prevailing national characteristics — turbans for the Indians, kimonos for the Japanese, sampan hats for the Indonesians. (A Jew himself, Neurath seemed to have an impish sense of humor: The grass-skirted and goggle-eyed figures representing "primitive cults" were exactly the same as for the Jews, except that the Jews stood on little starred boxes.)

Ernst Gombrich’s Eine Kurze Weltgeschichte für Junge Leser (Little History of the World for Young Readers), 1935, offers another striking exception. Still in print today, the book — derived from Gombrich’s doctoral thesis — was written principally for the young daughter of friends, who wanted to know what engaged him so deeply during his work day. The book begins with the caveman and ends just after WWI. Formally and conceptually progressive, it was later banned by the Nazis for its inherent pacifist message.

Shortly after, in 1938, Austria was annexed to Germany, and the ensuing catastrophe of World War II all but buried the ideals behind the radical Kunsterziehung movement. Steering youth to art now seemed as irrelevant as Art for Art’s sake. But as these works show, publishers remained committed to children’s books up to this point, even if the impulse to educate and challenge young readers through art — as in the utopian ideals of the Century of the Child — were long gone.

Viennese children’s book illustrations at the time were no exception. They flaunted the same overripe aestheticism, as can be seen in Heinrich Lefler’s illustrations in Die Bücher der Chronika der drei Schwestern (Book of Chronicles of the Three Sisters), 1900, whose rampant geometric patterning and insane detailing heralded the arrival of modern book art in Vienna. Lefler’s finest work and no less ornate Schiller-Festgabe der Stadt Wien (Schiller Festschrift of the City of Vienna) was printed and distributed to schoolchildren in 1905 — in bulk and free of charge — on the centenary of the death of the German poet Friedrich Schiller. Other examples were particularly striking because they weren’t only directed to children. Leading artists like Koloman Moser designed children’s books while using them as prototypes for their own work, while intellectuals Otto Neurath and Ernst Gombrich also contributed to the genre — the former with his pictogram innovations, the latter with easier-to-digest versions of his theoretical writings.

But Viennese children’s books hadn’t always been so decadent, nor city officials so benevolent. Only as recently as 1883 had a child labor law mandated that children rest at least one day a week from their 11-hour-long factory shifts. Soon after, Swedish pedagogue and feminist Ellen Key proclaimed the start of the Century of the Child, and it was in this spirit that a lifelong involvement with art was seen as essential to children's development. Viennese educators inaugurated the Kunsterziehungsbewegung (art education movement), a direction in art pedagogy that was closely tied to the Jugendschritftenbewegung, or youth magazine movement. Between 1897 and 1902, the Austrian Ministry of Education commissioned 33 contemporary artists to produce Bilderbogen für Schule und Haus (Picture Sheets for School and House), inexpensive teaching materials. Magazines such as Für die Jugend des Volkes (For the Youth of the Nation), 1892-1898, targeted children of poor families and were accompanied by remarkable illustrations from artists Koloman Moser, Leo Kainradl and Alexander Pock, the immediate forerunners of the Vienna Secessionists who rebelled against the era’s stale codes of academic art. Art, these young upstarts proclaimed, should be a way of life.

Commissioned by the Austrian Ministry of Education, Für die Jugend des Volkes was a magazine targeted at children of poor families, 1892-1898

As a result, Viennese turn-of-the-century book illustrations often combined experimental forms with fine craftsmanship. Designed down to their bindings and spines, volumes like Die Nibelungen: Dem Deutschen Volke Wiedererzählt (The Niebelungen Legend: Retold to the German People) from Franz Keim, 1908, were Gesamtkunstwerke. Heinrich Lefler’s work in Hans Christian Andersen’s Die Prinzessin und der Schweinehirt (The Princesses and the Swineherd), 1897, used gold and silver plating in an overall subtle color mix to illustrate a gaggle of well-preened voyeurs ogling a kiss. Koloman Moser’s illustrations of terrified and drowning men in the Jugendschatz Deutsche Dichtungen, 1897, employed exaggerated thick lines that challenged traditional methods of rendering perspective.

This dedication to children’s books continued as Austria entered WWI, though now the idealism and freedom pulsing through earlier works were swapped for patriotic fever. Wir Spielen Weltkrieg! (Let’s Play World War!), published by the Kriegshilfsbüro des k.k. Ministerium des Innern zu Gunsten des Roten Kreuzes in 1915, is grimly instrumental but still visually appealing. Round-cheeked babes, plush toys and weapons, all drowning in intricate, ornate patterns, are paired with dialogue like: "Bitte, haben Sie den Feind gesehen?" (Please, have you seen the enemy?). Franz Wacik’s brilliant lithographs in Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter (Prince Eugene, the Noble Knight), 1915, serves as a rousing call to nationalism. The turbaned corpses of slain soldiers in the battlefield send a clear message, that Austria’s future lay in subduing the Balkans.

As a result, Viennese turn-of-the-century book illustrations often combined experimental forms with fine craftsmanship. Designed down to their bindings and spines, volumes like Die Nibelungen: Dem Deutschen Volke Wiedererzählt (The Niebelungen Legend: Retold to the German People) from Franz Keim, 1908, were Gesamtkunstwerke. Heinrich Lefler’s work in Hans Christian Andersen’s Die Prinzessin und der Schweinehirt (The Princesses and the Swineherd), 1897, used gold and silver plating in an overall subtle color mix to illustrate a gaggle of well-preened voyeurs ogling a kiss. Koloman Moser’s illustrations of terrified and drowning men in the Jugendschatz Deutsche Dichtungen, 1897, employed exaggerated thick lines that challenged traditional methods of rendering perspective.

This dedication to children’s books continued as Austria entered WWI, though now the idealism and freedom pulsing through earlier works were swapped for patriotic fever. Wir Spielen Weltkrieg! (Let’s Play World War!), published by the Kriegshilfsbüro des k.k. Ministerium des Innern zu Gunsten des Roten Kreuzes in 1915, is grimly instrumental but still visually appealing. Round-cheeked babes, plush toys and weapons, all drowning in intricate, ornate patterns, are paired with dialogue like: "Bitte, haben Sie den Feind gesehen?" (Please, have you seen the enemy?). Franz Wacik’s brilliant lithographs in Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter (Prince Eugene, the Noble Knight), 1915, serves as a rousing call to nationalism. The turbaned corpses of slain soldiers in the battlefield send a clear message, that Austria’s future lay in subduing the Balkans.

A lithograph by Franz Wacik for Prinz Eugen der edle Ritter, 1915

What began as a pedagogical commitment to children and a brighter future became eclipsed by the refusal to face a new and much-changed world. Against the books’ conservative and backwards-looking contents, the emphasis on style and form felt jarring. In his memoir, Stefan Zweig noted that “such overvaluation of the aesthetic, carried to the point of absurdity, could only exist at the expense of the normal interests of our age.” Writer Karl Kraus went even further, condemning the focus on aesthetics as “corrosive, oppressive and immoral.” If that sounds extreme, consider that when Austrian Emperor Franz Josef I died in 1916, the education ministry designed and printed thousands of copies of an extravagant commemorative book, Kaiser Franz Josef I, Ein Erinnerungsbuch (Emperor Franz Josef I: A Memoir), as a gift for schoolchildren. No matter that the monarchy had long lost its ability to rule and Austria was on the verge of dissolution. Worse even was that the intended schoolchildren were literally starving to death; the shortages caused by the Allied blockade resulted in widespread malnutrition, wiping out as much as 30 percent of the population.

It was only after the First World War and the founding of the new Austrian republic that new opportunities for illustration began to present themselves. The Social Democrats implemented their program of reform teaching in 1918, and Socialism — known as the era of Red Vienna — had begun to set in. One of the most popular youth magazines during this time was the Jugendrotkreuz Zeitschrift (Magazine for the Red Cross Youth), illustrated by the well-known artist Franz Cizek, which was committed to the goals of tolerance, peace and moral rebuilding of young people after the war.

Books like Hoch Die Republik (Exalt the Republic), 1918, were modern and optimistic, with clean lines once again representing hope for a better future. The book was intended as a gift for Viennese primary schoolchildren, but as a precursor of hardships to come, was eventually banned. The Ministry of Education — later dominated by the conservative Christian-Social Party — criticized the depiction of certain social democratic ideals. And many weekly children's publications — including Der Regenbogen, Wochenschrift für Kinder (The Rainbow: Children's Weekly), 1924-27, and Der Weg ins Leben (The Path to Life), 1924, met with the same fate. The latter’s covers exemplified “Viennese Kineticism” with streaks of chalky black, vibrating with energy and spirit. Inside, the texts pondered rational enlightenment, pacifism and an activist view of life.

Der Regenbogen, Wochenschrift für Kinder (The Rainbow: Children's Weekly), 1924-27

More acceptable in a political sense were books like Buch der Arbeit (Book of Work), 1922, where labor was idealized through factory scenes of puffing smokestacks, with workers reduced to ant-like miniatures in the foreground. Published by the Social Democrats and printed from 1923 to 1934, the Constructivist-influenced Kinderland, die Zeitung der Osterre Arbeiterkinder und Bauernkinder (Children's Land: The Newspaper for Austrian Workers' Children and Farm Children) was more typographically progressive and more widely read.

Around this time, as Austria’s political situation steadily worsened, so finally did children’s pictorial worlds. Curator Friedrich C. Heller links the waning artistic quality to the rise in popularity of “cute modes of representation” as seen in the saccharine Kind und Zeit (Child and Time), 1927. Other examples were books for city children that aestheticized country and peasant life.

Nevertheless, two remarkable books would still be published over the next decade. The first was Otto Neurath’s Die Bunte Welt (The Colorful World), 1929, a pioneering example of graphic design and visual communication. Neurath had attempted to develop a universal visual language which is reflected in the book’s tables, such as "The Population of Asia, not including East Asia and Australia," and "Followers of the World’s Major Religions." Here, Neurath illustrates population figures with simplified composites of the then-prevailing national characteristics — turbans for the Indians, kimonos for the Japanese, sampan hats for the Indonesians. (A Jew himself, Neurath seemed to have an impish sense of humor: The grass-skirted and goggle-eyed figures representing "primitive cults" were exactly the same as for the Jews, except that the Jews stood on little starred boxes.)

"Followers of the World’s Major Religions" from Die Bunte Welt, by Otto Neurath, 1929

Ernst Gombrich’s Eine Kurze Weltgeschichte für Junge Leser (Little History of the World for Young Readers), 1935, offers another striking exception. Still in print today, the book — derived from Gombrich’s doctoral thesis — was written principally for the young daughter of friends, who wanted to know what engaged him so deeply during his work day. The book begins with the caveman and ends just after WWI. Formally and conceptually progressive, it was later banned by the Nazis for its inherent pacifist message.

Shortly after, in 1938, Austria was annexed to Germany, and the ensuing catastrophe of World War II all but buried the ideals behind the radical Kunsterziehung movement. Steering youth to art now seemed as irrelevant as Art for Art’s sake. But as these works show, publishers remained committed to children’s books up to this point, even if the impulse to educate and challenge young readers through art — as in the utopian ideals of the Century of the Child — were long gone.