Called “the most influential woman graphic designer on the planet” by fellow designer extraordinaire Ellen Lupton, Pentagram partner Paula Scher has left an undeniable imprint on the American design psyche. The monograph Paula Scher: Works, now available for pre-order in paperback, beautifully covers a body of work that spans decades and industries. It was no small task. I sat down with Paula and asked her about the experience of being curated, what she learned in the process, and what she’s focused on now (which as it turns out, has a lot to do with forward motion).

Julie Anixter: Tell me about this book.

Paula Scher: Unit Editions, an amazing publishing company, produced it. I didn't make this book, they did. So it's even more delightful, because I didn't have to do very much work. I just did the work in it.

JA: It's different than other books that you've published. It feels like a memoir. Is this your memoir?

PS: It is a memoir of work. There's no question about it. I mean, it's a lifetime of work.

JA: Can you give us the backstory? Why did you want to do this right now?

PS: You know, it was a bit accidental and happenstance, as most things are. I hadn't done a book of my graphic design work since 2002 when Make It Bigger came out, but I had also published a book of paintings three years ago. I didn't feel like “I’ve got to do a book.” But I thought that what existed of my work that people knew was not very current, which I didn't feel great about.

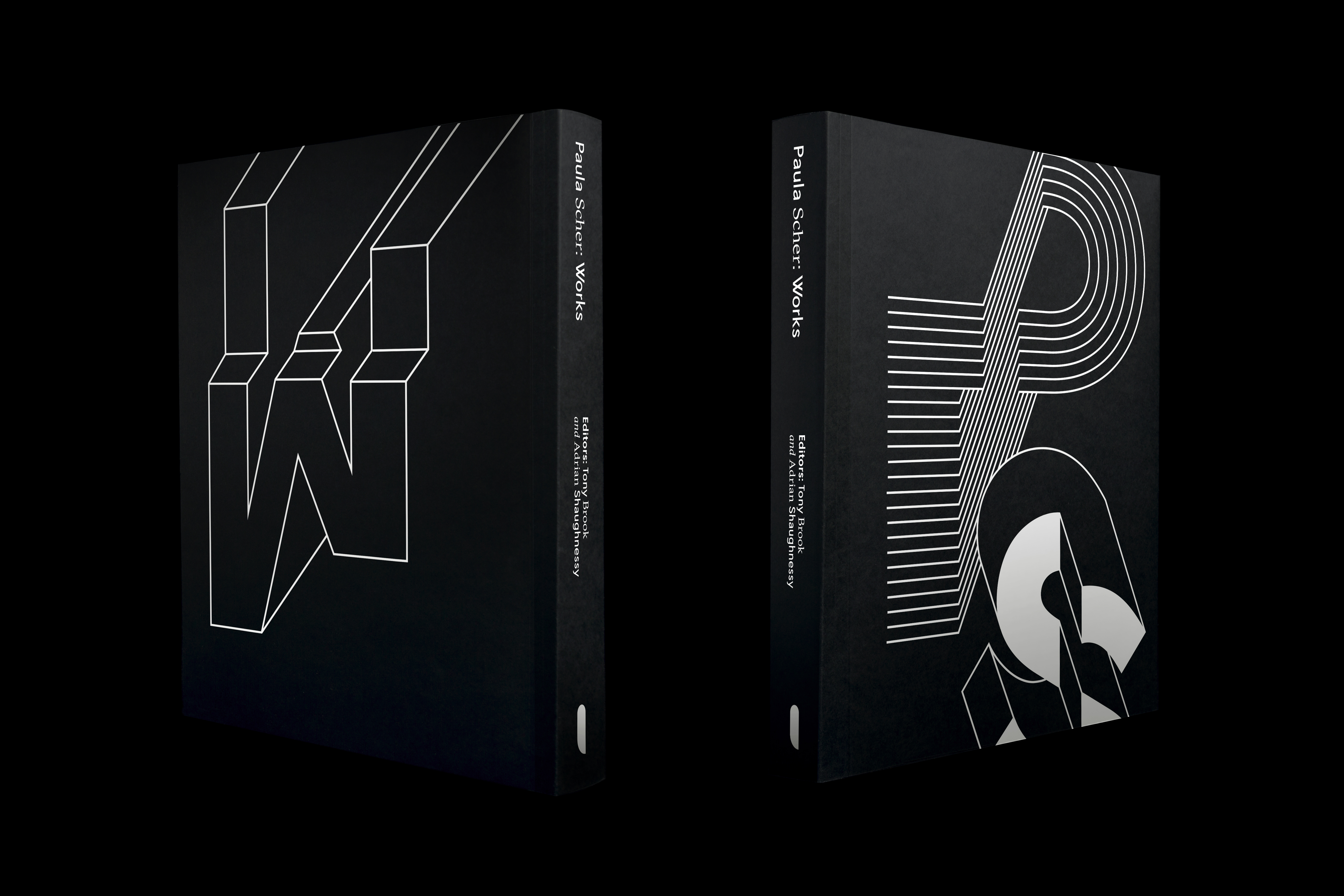

By pure happenstance Tony Brook and Adrian Shaughnessy, who are both friends of mine, were in town working on Lance Wyman's book. They took me out to dinner, which was not unusual because we have dinner all the time, and they asked me if I would be interested in having them publish a book on my work. I almost fell off my chair because it never occurred to me that it would be a possibility that someone else would do it. It wasn't that they were asking me to author the book. It was their book.

JA: Are there many people in the world that you would have trusted to do this?

PS: No, there's no one else in the world. There's no one else in the world—except for perhaps one of my partners—that I would trust to lay out design and edit a book on my work. I mean, Tony picked all the work. He curated the book.

JA: That's amazing.

PS: We met the next time in the conference room at Pentagram. I pulled out the work, took them through the decades and the kind of work I do, and gave it to them.

JA: What was the process like?

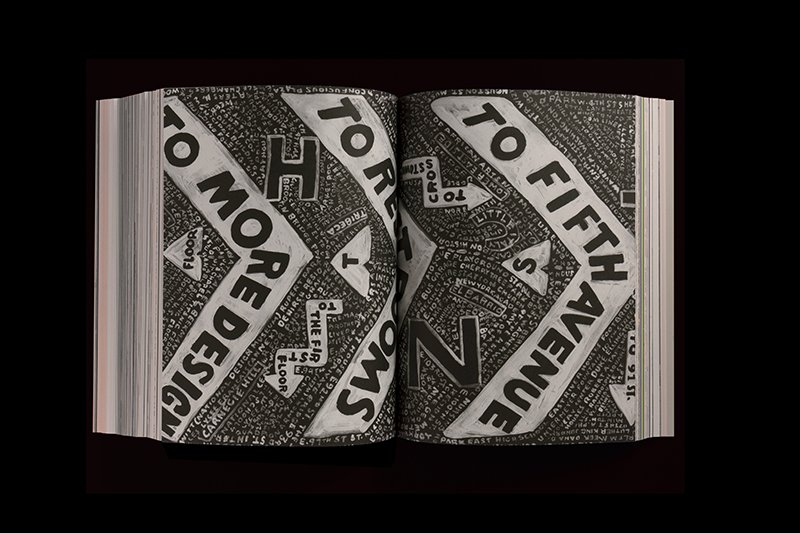

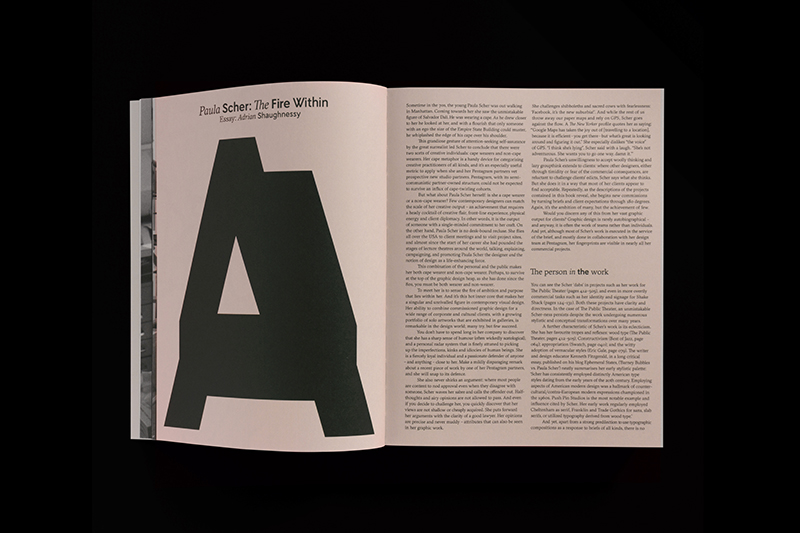

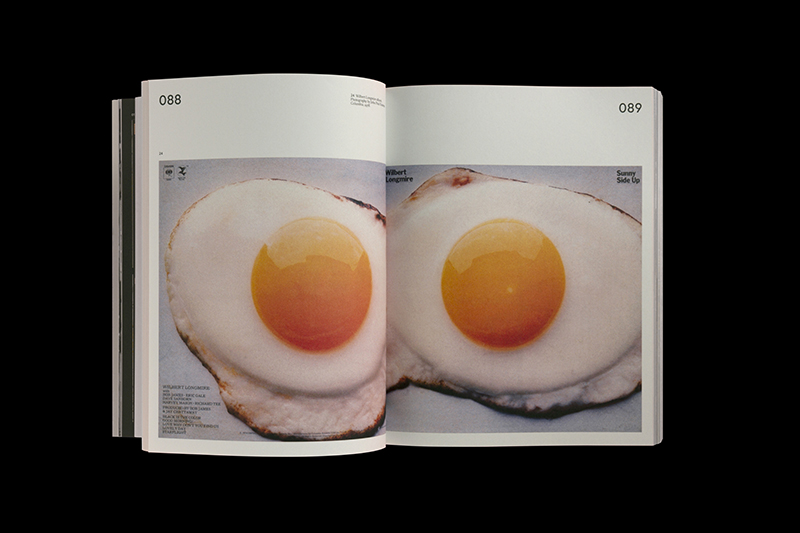

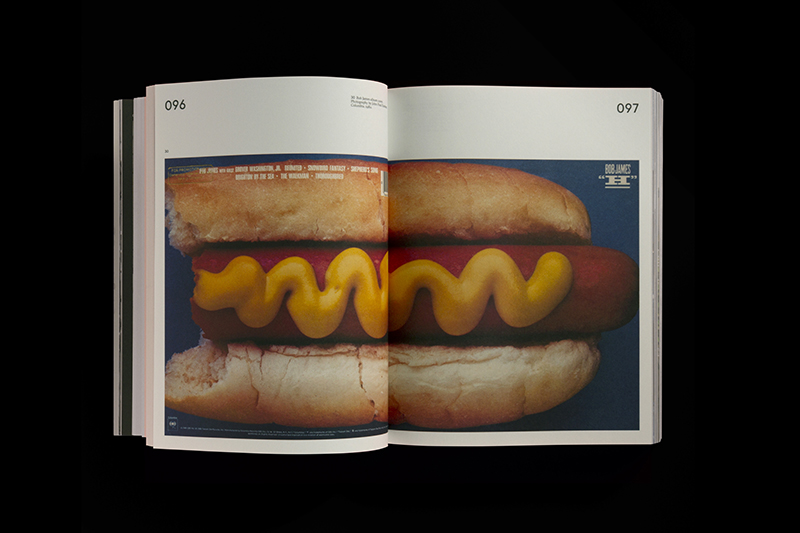

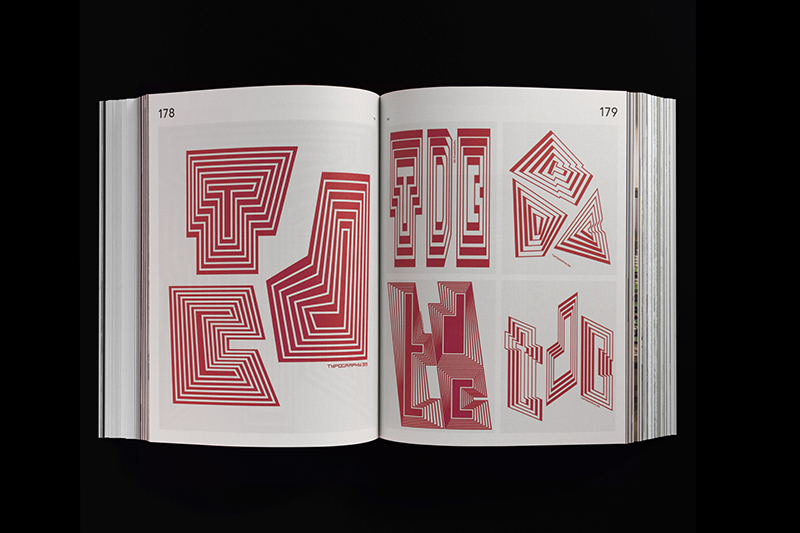

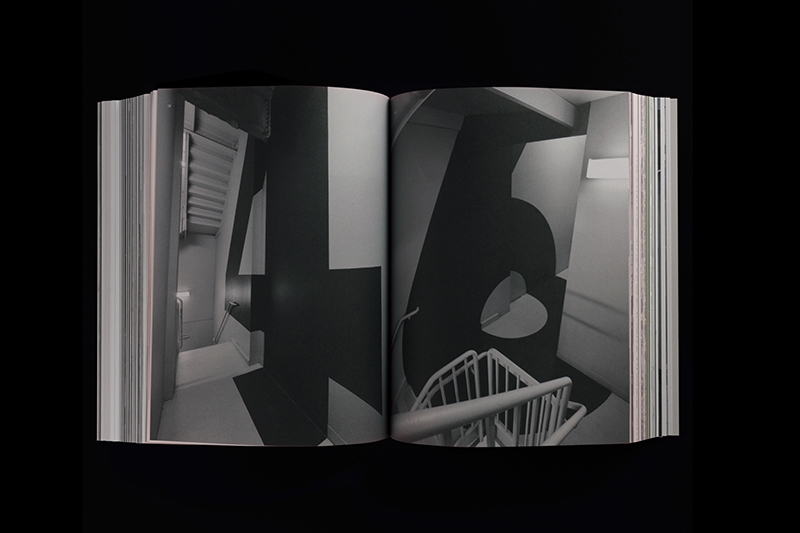

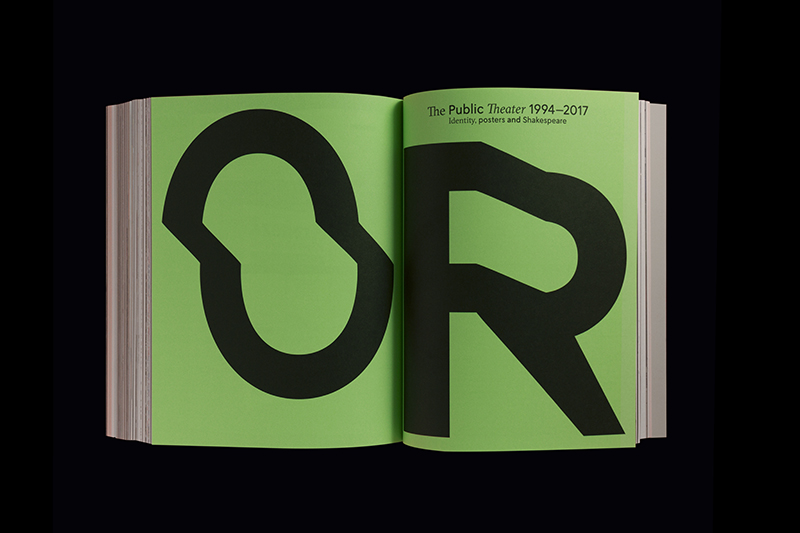

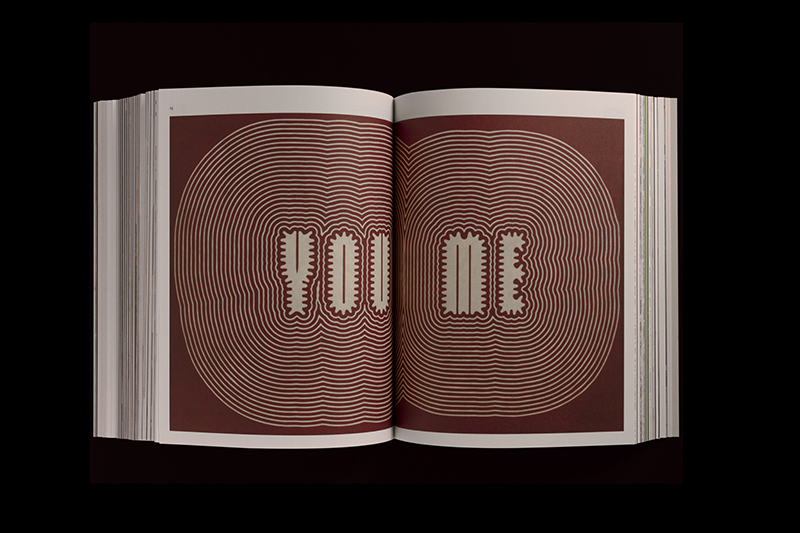

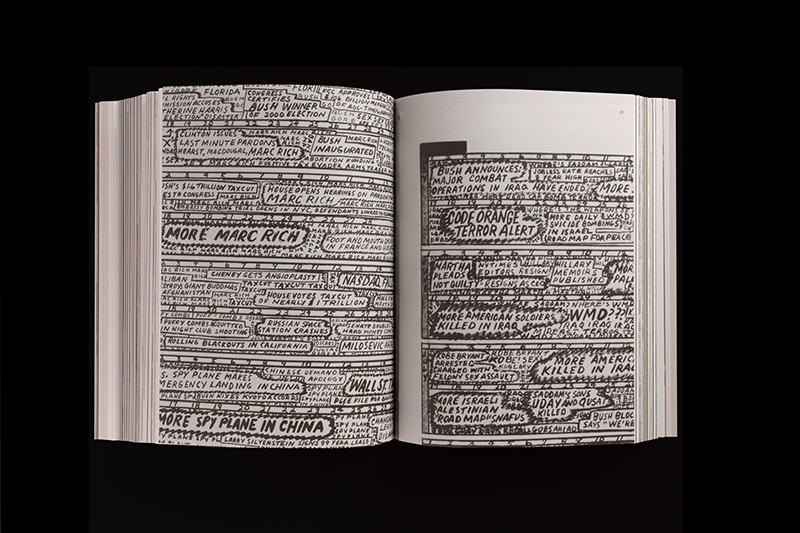

PS: We had a back and forth to make sense of the content. It was chronological but also by type because I worked in so many areas. The record industry's its own thing; then there's a whole history of identity work and environmental graphic design work and personally authored work. Then what do you do with The Public Theater? It's just too big to stick in the identity section. There was a fair amount of trying to figure out how those things functioned as a book. But other than back and forth on chronologies, he laid the whole thing out.

JA: So it sounds like it was ‘collaboration-light’ for you? What that a relief?

PS: For me it was. I really did not interfere with the book. The book’s jacket was a complete surprise and delight. He chose these opposing typefaces that I thought were so bizarre when I saw them that I said so. And he said, “you'll get used to them!” I did.

JA: It’s been a big year. You also were the subject of the Netflix documentary, Abstract. What was that like?

PS: The director, Richard Press, is the guy who did the Bill Cunningham film. He shot me for four days. He knew who I was. He interviewed me, and he caught something about my passion for typography and what I make. He really understood that these things that are “identities”—that exist in any form of media—are made. It's not a bunch of strategists in an office, and you whack it out digitally on a computer. The feedback I got from the film was from all walks of design life. It seemed like they all got back to the same longing of making stuff. That seemed to be what resonated.

Identities—that exist in any form of media—are made. It's not a bunch of strategists in an office.JA: Back to the book. What has surprised you or what have you learned from it?

PS: It's a strange thing because I didn't make it. It's become this object that's outside me. I don't feel connected to it in the same way I did to Make It Bigger, which was something that had both my work and my writing in it. It was about how I thought about design and designing. Whereas this is an interview with me; it's got my life in it. I see these pictures about my life, and I see all this work I did over the years. There are things that I'm still charmed by. There are things that I don't know if I think are good enough. There are things that I'm amazed that I did. But it's the past and I already want to work on the next stuff. Here's 45 years. Okay. On to the next.

JA: Since you had to let go of control and it was outside of you, in a sense, you were the material.

PS: Right. I'm a dead person. You know?

JA: Hardly.

PS: But it's usually a dead person.

There are things that I don't know if I think are good enough. There are things that I'm amazed that I did. But it's the past and I already want to work on the next.

JA: So, speaking of not being a dead person, what are you working on now?

PS: I just finished a terrific clump of work and I loved all of it. Some of it even made it into the book, like Planned Parenthood and the Quad Cinema, which is one of best environmental projects ever. Go see it if you can. But, what's on the horizon, with the exception of one environmental graphics project, is not terribly interesting.

I get really exciting work in clumps— the Heart and Stroke identity, Planned Parenthood, Period Equity, the Quad, Pasadena Playhouse, and the Public season again. They all sort of came at once and were within maybe a eight-month period. And they’re just one after another. And now I'm looking at the next phase and thinking, “nah…”

JA: I remember reading an essay years ago about the dark night of the soul. The thesis was that you cannot be exposed to the light all the time because you would burn out, being too close to the sun. So, the soul has to go dark—to recover and be able to experience the light again.

PS: I think that's happened! You're either the soul or you're the soul of the client base. I can't tell which.

I think the biggest surprise was how I felt like the object of the book was something separate from me. That what was inside the book was a history of things I'd done and that exist. You know; some of them still go on. And that I'm a separate person just walking forward. I didn't feel like it defined me. I don't feel even that emotionally connected to it. It's this record that I know is there, but I'm still a person. So I have to keep walking. I have to get some other decent jobs.

The problem with getting wonderful things to work on is they don't come every day, and so when you're sitting around going, god, this is really kind of ordinary-looking work I'm getting here.

JA: Do you ever just go to people and say, "I'd love to talk to you about your company or brand?”

PS: No, never. That's a very advertising-esque approach. No, I never do that. I sit around and wait for somebody to like me.

JA: So you're waiting for the waves to roll in?

PS: No. It really is: Work brings work. Things run in cycles. So I tend to get three of the same kind of jobs at the same time. They're sort of magical. They come in three's. They usually come at unrelated times. I have good luck and I have bad luck, and I have periods where I feel immensely productive and periods where I feel fallow. I just had a very productive year. So I'm in fallow land.

JA: Paula, for some reason, I’m not too worried about you.