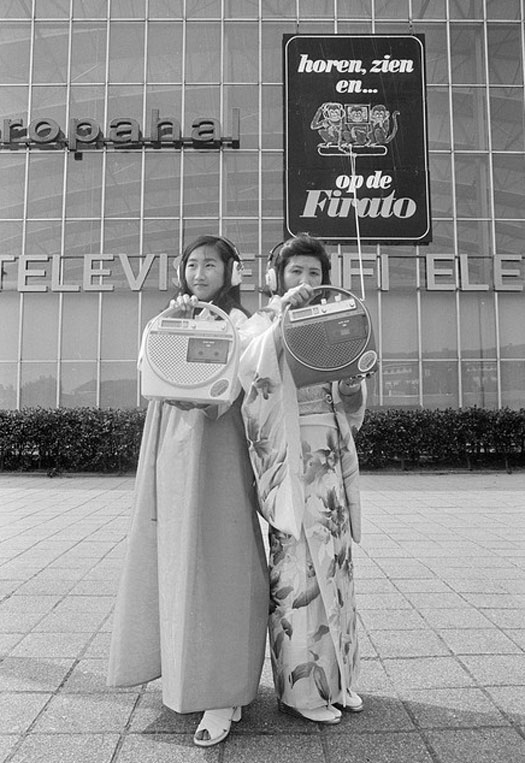

"Japanese Girls Demonstrate Radio-Cassette Players," 1974. Source: Flickr Commons

The news about the Walkman arrived about the same time as Richards’s bestselling book Life, written with James Fox. Read it and you will discover a shrewd analyst of media innovation, in the company of Marshall McLuhan, Lewis Mumford, Siegfried Giedion and Edward Tenner.

“I’ve learned everything I know off of records,” says the guitarist-turned-historian of technological innovation.

What is important, Richards declares, is “being able to replay something immediately without all that terrible stricture of written music, the prison of those bars, those five lines. Before 1900, you’ve got Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Chopin, the cancan. With recording, it was emancipation for the people.

“It surely can’t be any coincidence that jazz and the blues started to take over the world the minute recording started, within a few years, just like that.”

Richards’s point may be obvious, but it is still overlooked: Recording did for music what writing did for literature. It supplemented, then nearly supplanted, the live performance. Recording gave artists access to the music of the past to a far greater degree than mere live performance. Distance, cash and class kept many people from the concert hall or even the cabaret.

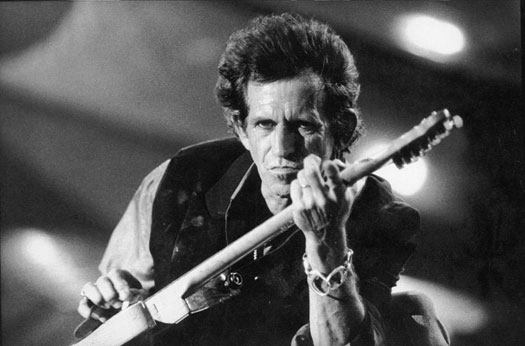

Keith Richards on Rolling Stones Voodoo Lounge world tour, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1995. Source: Wikimedia

Keith Richards on Rolling Stones Voodoo Lounge world tour, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1995. Source: Wikimedia

The history of innovation in mobile audio is not very long. It begins with wind-up phonographs, which became widely affordable in the 1910s and 1920s. The importance of this technology cannot be overestimated. Everywhere, but especially in the rural American South, it was a device of astonishing modernity, whose arrival in the still unelectrified farms and small towns made as powerful an impact as television later would. It not only transformed the culture of the domestic interior but also could be carried outdoors, to dances and picnics.

Lawrence W. Levine’s excellent 1977 cultural history Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom explains how the wind-up phonograph created a whole separate market for “race music” that gave birth to the recorded blues. From that category, of course, grew the whole family tree of pop music that includes R&B, rock and roll and more.

According to Levine, by 1920 or so, one could hear blues drifting out of open windows in black neighborhoods. Zora Neale Hurston visited plantations and lumber camps and recorded the influence of the “mechanical nickel phonograph” or juke box around the same time.

The huge sales of records like Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” of 1920, generally regarded as the first blues song, led to a rush of (white) producers to the field. By 1930, Bessie Smith had sold an estimated 10 million records.

Radio nearly killed the recording industry. It was widely available in homes by the early 1930s. Beginning in the early 1950s, car radio offered another critical form of portability that shaped the popular music business. Hits had to sound good on tinny speakers accompanied by wind noise. In his book, Richards recalls how the Stones would rush tracks fresh from the recording studio to favored local DJs. Then they got into a car to determine how well the songs sounded on car radio. (Punk artists, I seem to remember, also bragged ironically of albums with “genuine car radio sound.”)

The battery-powered radio and the plug-in phonograph that could be carried around became common in the late 1950s. In Richards’s accounts of his early influences — girl groups and Robert Johnson, which he heard on American records — he recalls one of his rivals: John Lennon owned a “30-pound portable jukebox, the 1960s version of today's iPod." The Discomatic player packed with some forty 45-rpm singles was the basis for a 2004 PBS documentary. The selection of songs — Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, Gene Vincent, the Contours — mapped the influences that shaped Lennon’s music.

The transistor radio with earphone came along circa 1955. The cassette tape, developed by Philips, arrived in 1962 and eventually allowed recording tape to become portable. This technology took two forms: One was public — the boombox — and one private — the Walkman. But both allowed personalizing recorded music, making “mix tapes,” in anticipation of the iPod. The boombox era of huge “ghetto blasters” coincided with the first stirrings of hip hop. It is recalled in Lyle Owerko's new book, The Boombox Project.

The Walkman, credited to engineer Nobutoshi Kihara under the direction of Sony boss Akio Morita, came from stripping the recording capability from a tape recorder used mostly by reporters. The first Walkman was an expensive, chic item.

Original Sony Walkman, 1979

The message also shaped the medium. Conductor Herbert von Karajan is famously responsible for the length of playing time on the compact disc. In the early ’80s, the Sony and Philips executives trying to gain his endorsement for the new medium, impressed him by fitting all of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as performed by his orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, on a single disc. By 1984, that disc could be carried around like a tape player: The Discman joined the Walkman. In 1999 came the first portable MP3 devices, in which digits replaced grooves. And in 2001, the iPod was introduced.

The process continues with such recent products as the Jawbone Jambox, designed by Fuseproject. The Jambox is a wireless speaker that connects by Bluetooth to mobile phones and other devices, combining both iPod and boombox traditions. (It can also serve as a de facto conference calling system.) Fuseproject says that the presentation of the Jambox “romanticizes the original boom box with its ‘sneaker box’ packaging.”

Technology has always shaped the way music is made — the spinet and harpsichord gave way to the piano, the Gibson to the Fender. Greg Milner’s book Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music shows how deeply and subtly our sense of music is influenced by recording.

Multi-track tape recording made many things possible in the studio: multiple tracks meant multiple tricks. Songs or symphonies could be recorded in several takes edited together. Performers could lay down their parts continents apart.

Even improvements in the humble turntable led to innovation in music making. DJs turned into producers and then into artists, thanks to the hand-manipulated turntables of the 1970s. Not long after Sony announced the end of the Walkman, Panasonic said it would stop building its Technics 1200 turntables, prized by DJs since the days of disco and early hip hop. The 1200 replaced older belt drives with a magnet drive that allowed for synchronizing beats and “scratching.” It arrived in 1972 and sold some 3.5 million units, making sampling possible before digital technology.

Similarly, Richards describes the way in which portable tape players changed his sound. Just as turntables influenced the birth of hip hop, the often overlooked cassette player helped in song writing and affected the way he played the guitar.

“I’d discovered a new sound I could get out of acoustic guitar,” he writes. “That grinding dirty sound came out of these crummy little motels where the only thing you had to record with was this new invention called the cassette recorder....Suddenly you had a very mini studio. Playing acoustic, you'd overload the Philips cassette player to the point of distortion so that when it played back it was effectively an electric guitar. You were using the cassette player as pick up and amplifier at the same time. We were forcing acoustic guitars through a cassette player, and what came out the other end was electric as hell.”

The lesson is an old one: When new technologies are widely distributed, dramatic change results. The same surprising effects that came with phonographs and tape cassettes also come when laser printers or laptop video-editing studios or laser stereo lithography machines get into the hands of people who figure out things to do with them that their inventors never imagined.

For Richards, technology had special utility. The tape player was also an invaluable aid to a musician who, thanks to drugs and alcohol, was not always able to recall his inspirations of the previous evening.

“I wrote Satisfaction in my sleep,” Richards claims. “I had no idea I'd written it. It's only thank God for the little Philips cassette player.” It was a miracle, he says. “I knew I put a brand-new tape in the previous night.” The next morning when he went to work, “I saw it was at the end. Then I pushed ‘rewind’ and there was Satisfaction . . . and forty minutes of me snoring.”

The recent announcement that Sony would cease manufacturing the Walkman in Japan raised eyebrows. Who knew they were still making them? It also reminded us that the history of mobile sound playing and recording has had a powerful influence on the way we experience and even make music. So says an astute commentator — Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones.

The news about the Walkman arrived about the same time as Richards’s bestselling book Life, written with James Fox. Read it and you will discover a shrewd analyst of media innovation, in the company of Marshall McLuhan, Lewis Mumford, Siegfried Giedion and Edward Tenner.

“I’ve learned everything I know off of records,” says the guitarist-turned-historian of technological innovation.

What is important, Richards declares, is “being able to replay something immediately without all that terrible stricture of written music, the prison of those bars, those five lines. Before 1900, you’ve got Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Chopin, the cancan. With recording, it was emancipation for the people.

“It surely can’t be any coincidence that jazz and the blues started to take over the world the minute recording started, within a few years, just like that.”

Richards’s point may be obvious, but it is still overlooked: Recording did for music what writing did for literature. It supplemented, then nearly supplanted, the live performance. Recording gave artists access to the music of the past to a far greater degree than mere live performance. Distance, cash and class kept many people from the concert hall or even the cabaret.

Keith Richards on Rolling Stones Voodoo Lounge world tour, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1995. Source: Wikimedia

Keith Richards on Rolling Stones Voodoo Lounge world tour, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1995. Source: WikimediaThe history of innovation in mobile audio is not very long. It begins with wind-up phonographs, which became widely affordable in the 1910s and 1920s. The importance of this technology cannot be overestimated. Everywhere, but especially in the rural American South, it was a device of astonishing modernity, whose arrival in the still unelectrified farms and small towns made as powerful an impact as television later would. It not only transformed the culture of the domestic interior but also could be carried outdoors, to dances and picnics.

Lawrence W. Levine’s excellent 1977 cultural history Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom explains how the wind-up phonograph created a whole separate market for “race music” that gave birth to the recorded blues. From that category, of course, grew the whole family tree of pop music that includes R&B, rock and roll and more.

According to Levine, by 1920 or so, one could hear blues drifting out of open windows in black neighborhoods. Zora Neale Hurston visited plantations and lumber camps and recorded the influence of the “mechanical nickel phonograph” or juke box around the same time.

The huge sales of records like Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” of 1920, generally regarded as the first blues song, led to a rush of (white) producers to the field. By 1930, Bessie Smith had sold an estimated 10 million records.

Radio nearly killed the recording industry. It was widely available in homes by the early 1930s. Beginning in the early 1950s, car radio offered another critical form of portability that shaped the popular music business. Hits had to sound good on tinny speakers accompanied by wind noise. In his book, Richards recalls how the Stones would rush tracks fresh from the recording studio to favored local DJs. Then they got into a car to determine how well the songs sounded on car radio. (Punk artists, I seem to remember, also bragged ironically of albums with “genuine car radio sound.”)

The battery-powered radio and the plug-in phonograph that could be carried around became common in the late 1950s. In Richards’s accounts of his early influences — girl groups and Robert Johnson, which he heard on American records — he recalls one of his rivals: John Lennon owned a “30-pound portable jukebox, the 1960s version of today's iPod." The Discomatic player packed with some forty 45-rpm singles was the basis for a 2004 PBS documentary. The selection of songs — Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, Gene Vincent, the Contours — mapped the influences that shaped Lennon’s music.

The transistor radio with earphone came along circa 1955. The cassette tape, developed by Philips, arrived in 1962 and eventually allowed recording tape to become portable. This technology took two forms: One was public — the boombox — and one private — the Walkman. But both allowed personalizing recorded music, making “mix tapes,” in anticipation of the iPod. The boombox era of huge “ghetto blasters” coincided with the first stirrings of hip hop. It is recalled in Lyle Owerko's new book, The Boombox Project.

The Walkman, credited to engineer Nobutoshi Kihara under the direction of Sony boss Akio Morita, came from stripping the recording capability from a tape recorder used mostly by reporters. The first Walkman was an expensive, chic item.

Original Sony Walkman, 1979

The message also shaped the medium. Conductor Herbert von Karajan is famously responsible for the length of playing time on the compact disc. In the early ’80s, the Sony and Philips executives trying to gain his endorsement for the new medium, impressed him by fitting all of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as performed by his orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, on a single disc. By 1984, that disc could be carried around like a tape player: The Discman joined the Walkman. In 1999 came the first portable MP3 devices, in which digits replaced grooves. And in 2001, the iPod was introduced.

The process continues with such recent products as the Jawbone Jambox, designed by Fuseproject. The Jambox is a wireless speaker that connects by Bluetooth to mobile phones and other devices, combining both iPod and boombox traditions. (It can also serve as a de facto conference calling system.) Fuseproject says that the presentation of the Jambox “romanticizes the original boom box with its ‘sneaker box’ packaging.”

Technology has always shaped the way music is made — the spinet and harpsichord gave way to the piano, the Gibson to the Fender. Greg Milner’s book Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music shows how deeply and subtly our sense of music is influenced by recording.

Multi-track tape recording made many things possible in the studio: multiple tracks meant multiple tricks. Songs or symphonies could be recorded in several takes edited together. Performers could lay down their parts continents apart.

Even improvements in the humble turntable led to innovation in music making. DJs turned into producers and then into artists, thanks to the hand-manipulated turntables of the 1970s. Not long after Sony announced the end of the Walkman, Panasonic said it would stop building its Technics 1200 turntables, prized by DJs since the days of disco and early hip hop. The 1200 replaced older belt drives with a magnet drive that allowed for synchronizing beats and “scratching.” It arrived in 1972 and sold some 3.5 million units, making sampling possible before digital technology.

Similarly, Richards describes the way in which portable tape players changed his sound. Just as turntables influenced the birth of hip hop, the often overlooked cassette player helped in song writing and affected the way he played the guitar.

“I’d discovered a new sound I could get out of acoustic guitar,” he writes. “That grinding dirty sound came out of these crummy little motels where the only thing you had to record with was this new invention called the cassette recorder....Suddenly you had a very mini studio. Playing acoustic, you'd overload the Philips cassette player to the point of distortion so that when it played back it was effectively an electric guitar. You were using the cassette player as pick up and amplifier at the same time. We were forcing acoustic guitars through a cassette player, and what came out the other end was electric as hell.”

The lesson is an old one: When new technologies are widely distributed, dramatic change results. The same surprising effects that came with phonographs and tape cassettes also come when laser printers or laptop video-editing studios or laser stereo lithography machines get into the hands of people who figure out things to do with them that their inventors never imagined.

For Richards, technology had special utility. The tape player was also an invaluable aid to a musician who, thanks to drugs and alcohol, was not always able to recall his inspirations of the previous evening.

“I wrote Satisfaction in my sleep,” Richards claims. “I had no idea I'd written it. It's only thank God for the little Philips cassette player.” It was a miracle, he says. “I knew I put a brand-new tape in the previous night.” The next morning when he went to work, “I saw it was at the end. Then I pushed ‘rewind’ and there was Satisfaction . . . and forty minutes of me snoring.”