In our studio, we find ourselves drawn to books at the intersection of multiple disciplines that are, more often than not, only accidentally visual: books about science and history, fiction and film, culture and language. While our personal interests differ greatly — Jessica is a painter and Bill’s focus is on social innovation — the thing that unites us is an enduring fascination with people’s lives.

Anne Carson, Nox

(New Directions Publishing, New York, 2009)

Anne Carson’s visual elegy to her lost brother is a thing of astonishing beauty, an accordion-folded tapestry of word and image, memory and reflection, grief and love. Can a life live on in the form of a book? “It is when you are asking about something”, Carson writes, “that you realize you have survived it, and so you must carry it, or fashion it into a thing that carries itself”.

William Boyd, Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960

(21 Publishing Ltd., Cambridge, 1998)

A literary hoax brilliantly rendered as visual biography. Boyd tells the story of Nat Tate, a postwar artist whose story unfolds as a sequence of narratives woven from the tales of others, all of them credible and compelling and real — even as Tate himself is pure fiction. Or is he? This is a book that moves between our desks, but one that has been ever-present for over a decade.

Christopher Payne and Oliver Sacks, Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals

(MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2009)

Beautifully researched, exquisitely photographed and expertly composed and edited, this book takes readers on an engrossing tour of abandoned state mental institutions across the United States. Though devoid of living souls, Asylum is every bit a portrait of a lost generation. It reverberates with human tenderness on every page. Extraordinary.

Carl Schoonover, Portraits of the Mind: Visualizing the Brain from Antiquity to the 21st Century

(Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 2010)

An astonishing look at the profoundly complex internal systems that correspond to our external lives. At once gloriously abstract in their gestural beauty and deeply powerful in their biological precision, these images remind us of the humbling source that is the stuff of life itself. See a slideshow of the book here.

Gregory Blackstock, Blackstock’s Collections: The Drawings of an Artistic Savant

(Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2006)

A retired pot-washer, Blackstock is also autistic and an artistic savant, whose book is comprised of visual lists: wasps and birds, cabbages and spatulas, trucks and clowns and roosters. Lovingly drawn, obsessively chronicled, Blackstock’s mind is at once disciplined and untethered. Part outsider art, part insider obsession, there’s something stunningly refreshing about page after page of these black and white drawings, the big bold handwriting, and no digital gestures in sight.

John Stilgoe, Shallow Water Dictionary

(Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2003)

This textbook for landscape architecture is about the language of landscape, the language of estuaries as physical place and ecological systems. Perhaps more importantly, as his skiff, the ‘Essay’, explores and records the estuaries of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, John Stilgoe’s writing is a record of the experience of place and language. As he notes: ‘Landscape that lacks vocabulary cannot be seen, cannot be accurately, usefully visited. It is not even theoretical, if theory means what the Greek root theoria means – a spectacle, a viewing.’ (More here.)

Chris Marker, La Jetée (The Jetty)

(Zone Books, New York, 2008)

The photographer as editor as designer as movie-maker is all contained within the genius of La Jetée, which was released as a film in 1964. As it stirs our emotions with memories, it also makes possible the construction of a never-to-be forgotten narrative sequence. It’s so simple: the epic novel told in the most minimal and constrained number of images. It’s the ultimate visual essay. (More here.)

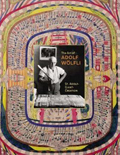

Elka Spoerri, The Art of Adolf Wolfli

(Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2003)

Adolf Wölfli was a mad artist, a schizophrenic, who spent 35 years in the Waldau Mental Asylum in Bern in Switzerland, being a graphic designer. Or so the argument goes. His work, contained in 45 hand-bound volumes with over 25,000 pages, is filled with prose texts, poems, fantastic narratives, myths, songs, travelogues, and musical compositions — an endless collage of calligraphy and illustration that creates a description of an imaginary cosmos. He is one of the lost souls of 20th century art. (More here.)

Hanns Zischler, Kafka Goes to the Movies

(University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2003)

Franz Kafka and Max Brod travelled Europe together, seeing movies in Zurich, Milan and other big cities. In the early days of the cinema, movies captivated viewers in ways we can no longer appreciate — it was magic, a life in the dark, a new lens into storytelling and dreams. Hanns Zischler has reconstructed the filmography of the movies that Kafka saw, and more importantly, he has created a new narrative around Kafka’s life that plants him firmly in the modern world. This is a title we designed a decade ago that still pleases us.