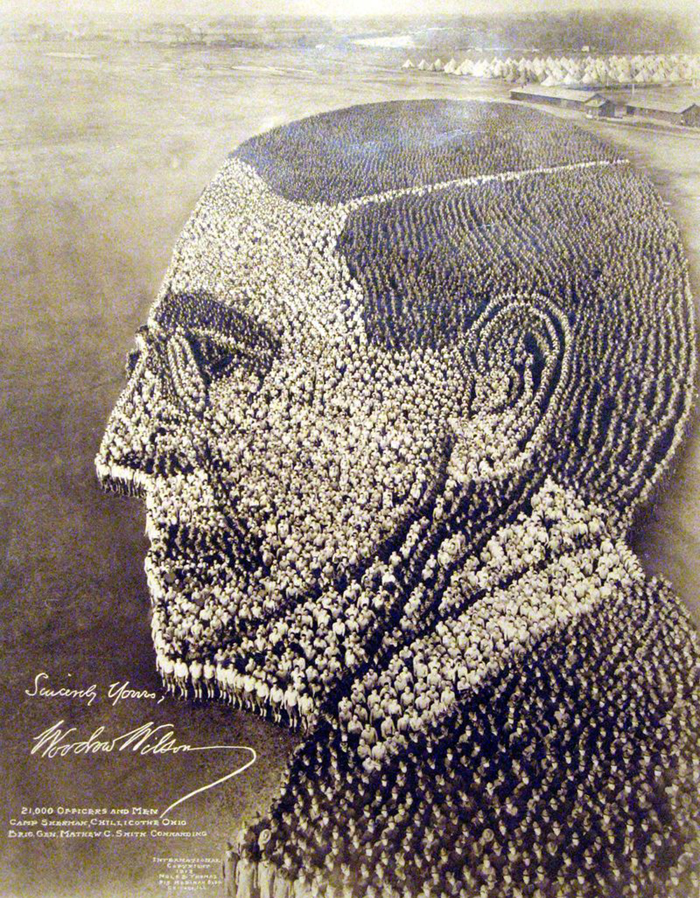

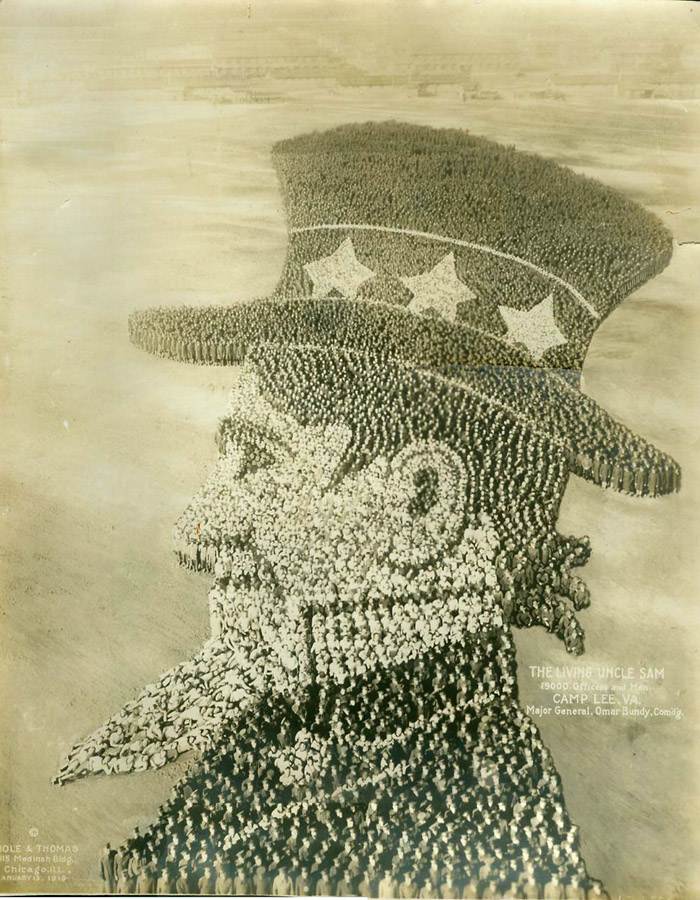

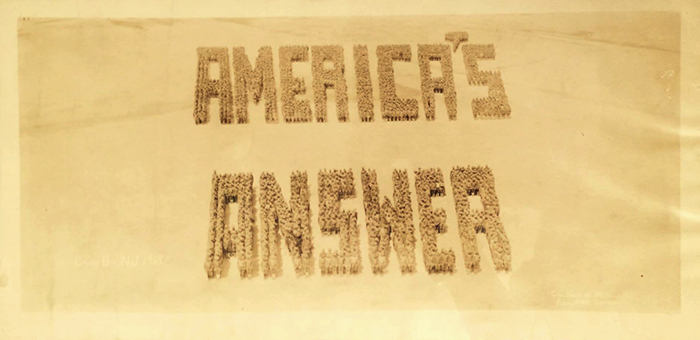

Arthur Mole (1889–1983) started out a commercial artist in England. In the first part of the twentieth century, he assembled and photographed large groups of churchgoers into religious symbols. It wasn’t until the outbreak of World War I that he had the idea to approach the military for similar, but patriotic concepts, using massive lines of obedient American troops to make the photographs.

By 1917 he had taken on an assistant by the name of John Thomas. The two would spend a week or longer planning and assembling these fantastic photographs, which Arthur Mole called “living pictures.” The photographs were sold in order to raise funds for the troops and care for the wounded when they returned.

Logistically, this project of extreme forced perspective was extraordinary. The team would first draw the outline they needed on the viewfinder of their large 11 x 14-inch view camera from an eighty-foot-high tower. The two men used megaphones and flags to communicate what they needed to assistants standing below. In order to calculate the number of men it would take to create a row, they would first take test photos of men standing shoulder-to-shoulder. Using this method they could calculate how many people were needed to complete a line. Next, they had to decide whether the men should wear dark or light shirts to complete the arduous task of making the tonalities of the picture correct. Published reports of their various projects say many soldiers fainted after enduring a full day in wool uniforms.

At around the same time, other photographers got in on the act, most notably E. O. Goldbeck, and, in 1920, 10,000 students and faculty of the University of Pittsburgh created their school mascot, The Panther—not bad for a non-military assembly.

Could a photo similar to the ones by Mole and Thomas be accomplished today outside of the military, and without digital trickery? What do you think?

++

Human American Eagle, made in 1918, was made using 12,500 officers, nurses, and men at Camp Gordon, Atlanta, Georgia.

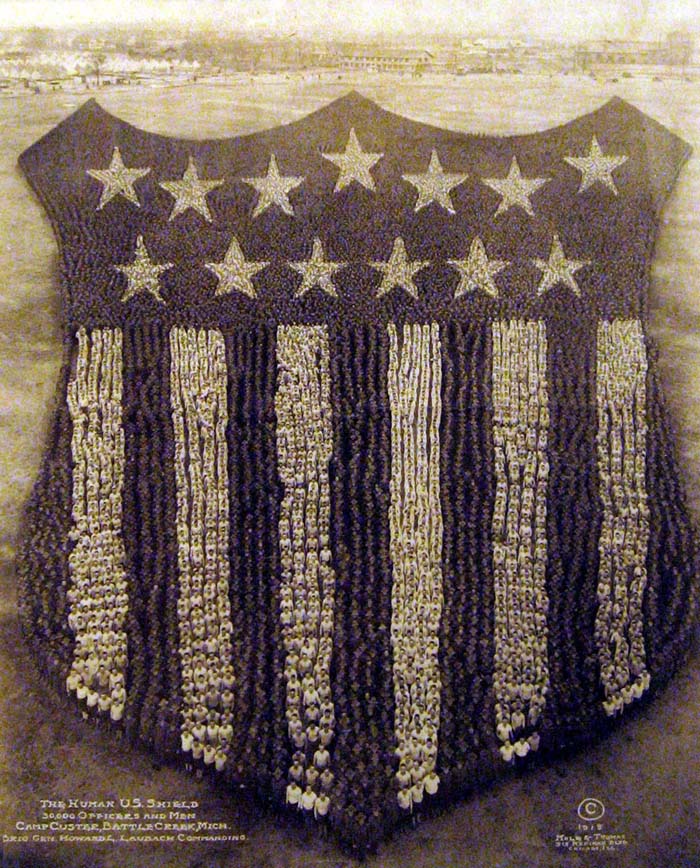

Human shield contained approximately 30,000 officers and men from Camp Custer, Battle Creek, Michigan.

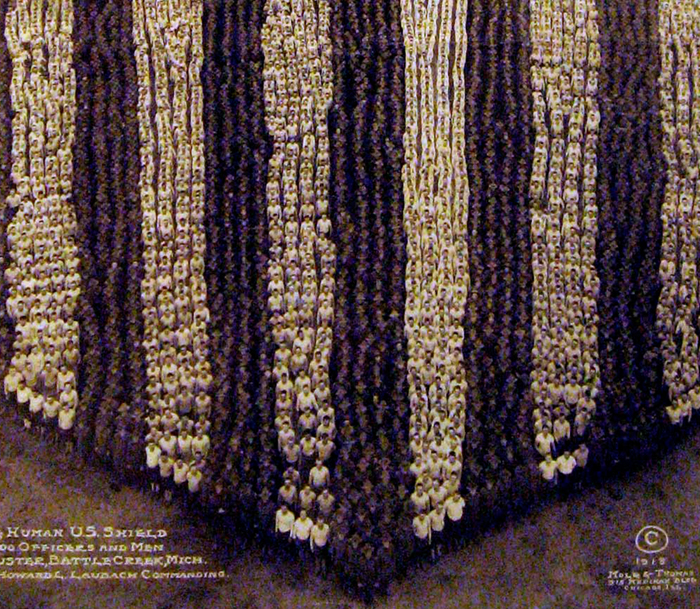

Detail of Human shield.

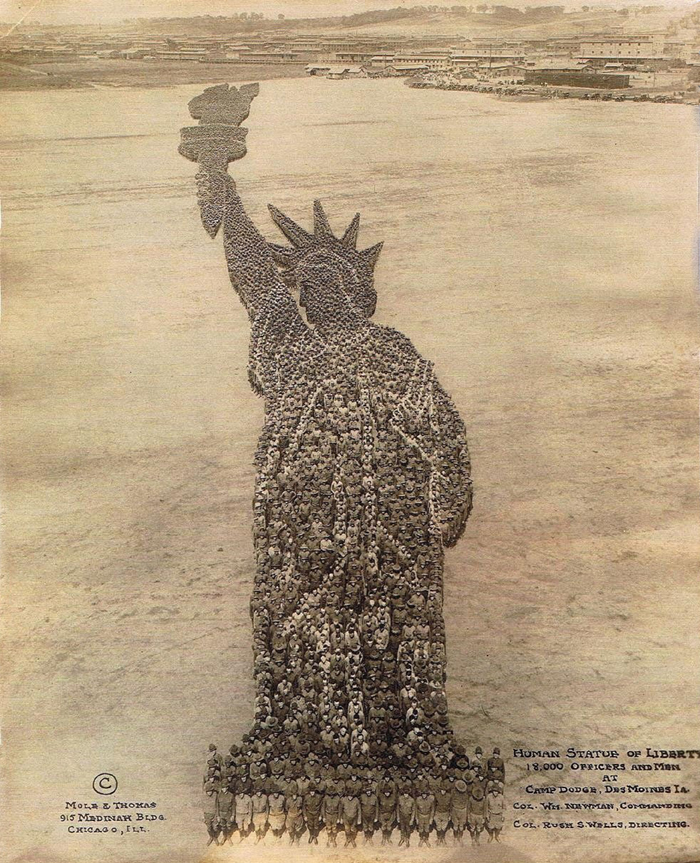

Statue of Liberty (1917) was composed of 18,000 officers and men from Camp Dodge in Des Moines, Iowa.

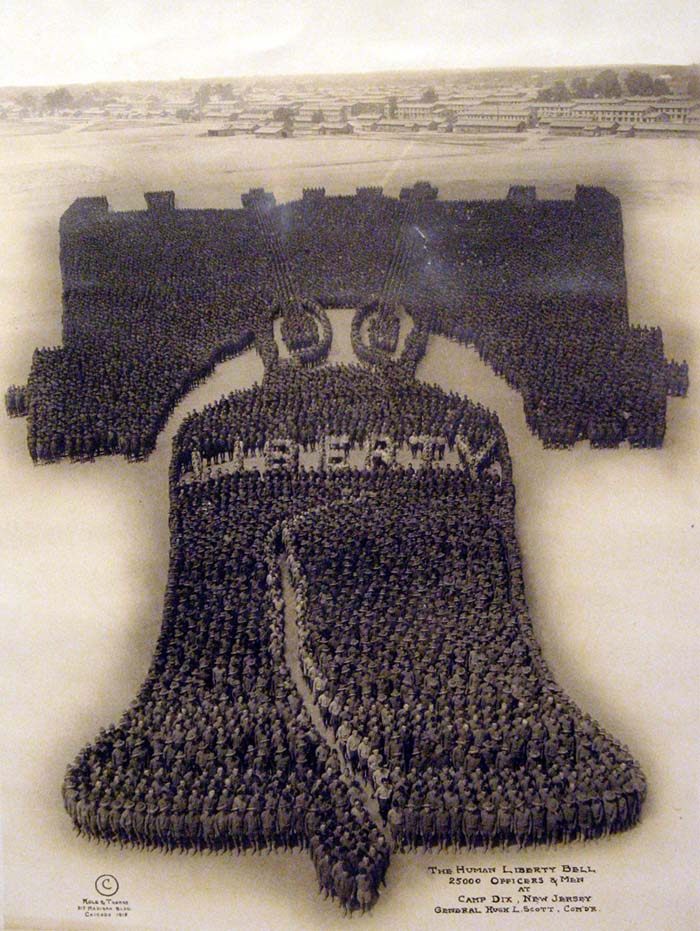

Human Liberty Bell, required 25,000 men and was made at Camp Dix, New Jersey, 1918.

Detail of Human Liberty Bell.

Portrait of President Woodrow Wilson, made with 21,000 officers and men at Camp Sherman, Chillicothe, Ohio, 1918. Collection of John Foster.

Living Insignia of the US Marines.

Living Insignia of the 27th Division, 1918, made of 10,000 officers and enlisted men.

The Living Uncle Sam, 1918, made of 19,000 officers and enlisted men.

The Panther, formed by the faculty and students of the University of Pittsburgh, 1920

Air Force Insignia, created by photographer Eugene O. Goldbeck, of the Indoctrination Division, Air Training Command, Lackland Air Base, 1917

America’s Answer, created by photographer Carl Halpern with officers and men of Camp Dix, New Jersey. 1918. Collection of John Foster.