By Maira Kalman, from On Looking

The other day I mentioned in passing that I sometimes give myself a “looking assignment” when I’m doing a lot of task-oriented walking. Before that I praised a street-art subgenre that draws attention to easily overlooked features of the built environment, and recently complained about technology that aims to filter your gaze through algorithms and commerce.

I’m hardly the first person to dilate on the virtues of seeing what others miss and/or seeing what nobody really wants us to see. But I mention all this to make clear that I was highly predisposed to enjoy the recent book On Looking: Eleven Walks With Expert Eyes, by Alexandra Horowitz.

I did. I’ve been thinking about why, and I’m hoping you’ll allow me to explain in some detail.

*

The book’s premise is implied in its subtitle: Horowitz went on walks with an assortment of “experts” in various fields, to try to learn how they see the world in ways she might have been missing. Some of her experts will be familiar to Design Observer readers — notably designer, historian, and typography expert Paul Shaw; illustrator, writer, and designer Maira Kalman; and Project for Public Spaces founder and president Fred Kent. Others are experts on geology, insects, urban wildlife. She walks with a doctor, a sound designer, a blind woman — and in what turns out to be a useful move, expands her definition of “expert” to include her 19-month-old son, and her dog, Finnegan.

The point of this exercise is not simply to describe the walks, or list everything the experts noticed, although there is some of that. (The descriptions of Shaw obsessing over unusual letterforms discovered in the urban wild are pretty charming.) Instead Horowitz is trying to draw some broader lessons about how we see, and how to see better.

This is harder to do than it sounds, because the big lessons are obvious or intuitive. We learn to overlook things because efficient seeing is not just useful but crucial: If your mind fails to prioritize recognizing a stop sign over the noticing a butterfly or an unusual rendering of the letter Q, you’re probably in trouble. As Horowitz suggests, the process of visual tuning-out, and organizing “the perceptual melee” that surrounds us into “chunks of recognizable objects” probably has evolutionary roots. (“Some things are good to eat, and some things are trying to eat you.” If our ancestors hadn’t figured out how to spot both, asap, we wouldn’t be here.)

*

On some level, I knew all that, and you probably did, too. Horowitz, who teaches psychology and previously wrote a best-selling book about the cognitive life of dogs, definitely has a popular audience in mind here. I assume an academic critic — whether from the perspective of science or visual culture — might find the book superficial. This is definitely not a sequel to, say, Ways of Seeing.

But she is often successful at teasing out more specific ideas about the way we look that I personally found useful; I’ve thought about this subject, but I’ve never studied it, so I appreciated having some terms to help frame whatever thinking I do in the future. And I was relieved that she pulled this off without resorting to an overload of trendy neuroscience babble — the citing of fMRI studies and naming regions of the brain that seems to have become mandatory in “idea”-driven" nonfiction these days. There’s a little of this (the “visual area” of the brain is called the occipital cortex, for whatever that’s worth), but it’s used judiciously.

Psychologists, Horowitz writes, call the human practice of focusing on certain visual cues above all others “selective enhancement.” Obviously there’s variation among specific humans in what our vision selectively enhances: It’s different for a typography expert and a geology expert, and this is essentially a function of repetition and practice. The idea comes up again in several ways. In one chapter Horowitz brings up the notion of the “search image.” This has nothing to do with Google; it comes from research exploring why songbirds tended not to eat new varieties of insect: They generally focused instead on what one researcher named the “search image” of whatever beetle they’d already learned to prey upon.

We use search images all the time — to spot a friend or find our keys, as Horowitz puts it. But the point is that the search image affects not only what we spot, but what we miss that’s right in front of us:

Jakob von Uexküll, the German biologist, wrote about this with his own search for a pitcher of water, which he expected to find at his table at lunch. Though he was assured that the pitcher was in its usual place, he could not see it right in front of his face—for the clay pitcher he had expected had been replaced by a glass pitcher. The “clay pitcher search image” obliterated the perceptual image of the glass pitcher.

In a subsequent chapter Horowitz circles around to what seems to me a closely related point. When her urban animal expert casually points out squirrel nests and bird sounds that Horowitz had completely missed, she concludes this is an example of how we see what we expect to see. Horowitz, like most city-dwellers, didn’t expect to see much in the way of wild-animal evidence; her companion did. “Expectation,” she writes, “magically sorts the world into things-we-are-looking-for and things-we-are-not.” This causes us to miss what we don’t expect to see — “inattentional blindness.”

*

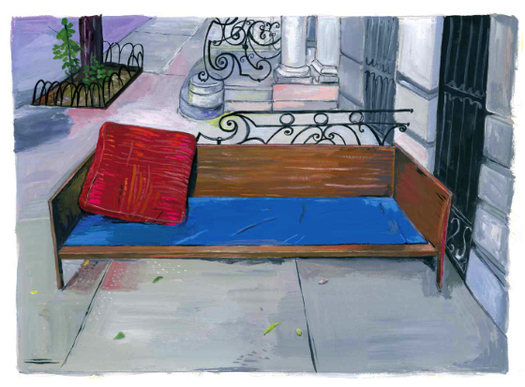

As my “looking assignment” habit suggests, I’m not just interested in the nomenclature of the way we see, I’m also looking for actual tips and tactics and strategies. (Maybe my tying to make security cameras a "search image" was a way of countering "inattentional blindness," in the instance I described.) The Kalman walk was interesting on this score: It took the pair two hours and covers a mere five blocks, evidently because Kalman felt compelled to wander into buildings — a halfway house, a church, a senior center — and ask questions. (Side note: Kalman contributed a couple of lovely paintings to the book, which I gather resulted from her walk with Horowitz; one of these is above, serving as evidence of the creative payoff of considered seeing.)

I was also intrigued by the bug expert’s habit of “flipping things over,” and by the doctor’s recollection of how his father encouraged him to be more aware of his surroundings: “We’d go someplace, and when we would leave, [my father] would ask us to draw a floor plan—where was the piano, where was the window. He knew. Once we did that a few times we started really paying attention.” That's pretty great.

Finally, Horowitz’ adventures made me consider what I’ll call empathetic or perhaps speculative looking. At one point she mentions how being slowed by recovery from back surgery made her realize how limitations can change how one sees, for instance. But the most memorable examples she deals with are perspectives we can only imagine.

The first walk Horowitz describes is with her child, whose random fascination with a dump truck, a stand pipe, an abandoned shoe, a particular play of shadows, represent exactly the “inability to feel that there is a difference between lovely and un-” that an adult can attempt to partially rediscover, but will never truly experience again. And the last walk she describes is with her dog, whose “merrily interested” explorations we can observe — but whose meanings and motivations we can never truly know.

*

Some of Horowitz’ walks are more informative than others. The chapters with the doctor and the sound designer both meandered too far off topic for me. And there are moments when her language is a bit precious for my taste (“I collected these sounds like beach pebbles, warmed in my hands and pocketed”).

But having acknowledged that I was pretty much in the perfect mood for a book like this, I really did get a lot out of it, and suspect that anybody interested in the art and practice of seeing will do the same.

In my occasional teaching turns, as with the stuff I write and the side projects I get involved in, I’m constantly returning to the idea of focusing on the overlooked and underrated. This book had me speculating about a whole class consisting of nothing but “looking assignments.” Maybe that already exists? Surely there are more such assignments than I have alluded to here, and more reading that is similarly instructive.

If you care to add to this conjectured curriculum, I welcome your suggestions.