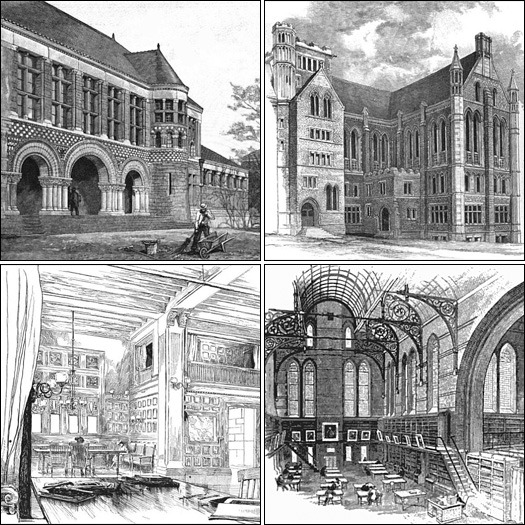

Illustrations from “Recent Architecture in America,” by Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer (Mariana Griswold), The Century Magazine, 1884.

This article was originally published in the September 2013 issue of Landscape Architecture.

Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer was one of America’s first architecture critics, prolific, connected, and deeply concerned with the ethics and aesthetics of building large and small, horticultural and industrial. She pioneered popular writing about landscape gardening (she preferred that term to “landscape architecture,” which caused debate with her friend and frequent subject Frederick Law Olmsted), and she wrote the first, still-respectable biography of H. H. Richardson. Her work has been neglected in recent history, an oversight that Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer: A Landscape Critic in the Gilded Age (University of Virginia Press, 2013), a new critical biography by Judith K. Major, aims to rectify. Major’s book firmly establishes Van Rensselaer as a key player in the rise of mainstream criticism, as well as situating her within a network of female professional peers including the muckraker Ida Tarbell and the architect Theodate Pope Riddle. (I wrote about Van Rensselaer and the legacy of female architecture critics for Places eariler this year.)

One of the incidental pleasures of Major’s book is the glimpse it gives into the life of a cultural journalist at the turn of the past century. Van Rensselaer’s husband died in 1884, and after that she often referred to herself as the “breadwinner” of the family. “Did she really need the money is beside the point. Van Rensselaer simply wanted to be treated as a professional and to be paid the same as male critics,” Major told me, quoting some period salary negotiations. “She asked Century editor Richard Watson Gilder in 1897 for the going rate of $30 per thousand words — approximately $760 today.”

Her pay rate remains enviable, but Van Rensselaer was also inexhaustible. Consider 1893, a year in which her primary focus was the World’s Fair in Chicago. Van Rensselaer approved of Olmsted’s unifying, earth-moving Beaux-Arts plans for the previously swampy site. On her first visit the grounds were not yet completed, but she wrote a two-part series for the New York World as if she were experiencing the exposition complete. Major writes of Van Rensselaer “passing through courtyards and archways, walking by the long expanse of the basin, and glimpsing ‘the further vista of pier and pavilion and limitless lake…the lake pale green under a morning sun, dark blue if the sunset is approaching.’”

Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer (Mariana Griswold), Art Out-of-Doors, 1893.

Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer (Mariana Griswold), Art Out-of-Doors, 1893.She eventually published articles about the World’s Columbian Exposition for Garden and Forest, the Century Magazine, and the Rand McNally & Co.’s Handbook of the World’s Columbian Exposition, while also writing 36 editorials for Garden and Forest ranging, as Major says, “from flowers to agriculture, from sculpture to fences.” She also wrote a short story for Century and a biographical piece on Olmsted, and published two significant books: Art Out-of-Doors and the Handbook of English Cathedrals, “all while she was traveling with her tubercular son to find a suitable climate.”

One of the contradictory aspects of Van Rensselaer’s career is her opposition to women’s suffrage, despite the fact that her colleagues were mostly men. Major told me, “Van Rensselaer believed that it was a woman’s role to influence and to educate, and this role overlaps with what Sir Sidney Colvin, a late 19th-century art critic, defines as the role of a critic: ‘It is the business of criticism to teach people how to look.’” At the time, Van Rensselaer was not alone in her belief that women and men had separate spheres, based on biological difference. Van Rensselaer acknowledged that she had stepped outside the women’s sphere as a public figure but said it was a “sacrifice for a good cause,” Major writes.

It may be Van Rensselaer’s contradictions that helped to make her such a wide-ranging critic, addressing the composition of a flower bed or the ravages of the motorcar. She complained (in 1913) about “the monstrous sign of a cigarette company that so terribly disfigures the viaduct at the end of Riverside Drive.” She used the circumstances of her life to influence the subjects of her criticism, and it is often her short, seemingly off-the-cuff editorials that paint the richest picture of the American architecture scene of the day.