The T.25 is barely over 8 feet in length and is expected to get 80 mpg. Photos courtesy Gordon Murray Design Limited.

Gordon Murray, the legendary automobile engineer, is known for building very expensive vehicles that go very fast. Born in South Africa in 1946, he began racing cars in the late 1960s, and went on to design Formula One models that have won dozens of events. He designed the McLaren F1 as a road-going race car whose top speed is around 240 mph and whose price, when it went on sale in 1994, was $997,000. Ralph Lauren claimed to prefer his FI to his Ferraris and Bugattis. “It was like piloting a rocket ship,” he said.

For years, Murray has discussed a plan to revolutionize city cars as much as he transformed race cars. And now that ambition seems to be on the verge of fulfillment. Last month, at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment in Oxford, England, he introduced his prototype for the T.25: a car that weighs just 1,212 pounds, extends a bit more than 8 feet long and is expected to get about 80 mpg — a car so tiny that three can occupy a parallel parking place, facing the curb.

The T.25 is shorter than the Smart ForTwo (106 inches), the Toyota iQ electric (117 inches) and the comparatively hulking Mini Cooper (145 inches) Thanks to a novel seating mode, it is also narrow — barely four feet wide — so two streams of the cars can pass side by side in a single conventional traffic lane.

T.25 dashboard.

Such innovations come naturally to a man, who, like Saint Paul, underwent a radical conversion on the road — in his case, in a traffic jam on England’s A3 motorway in 1993. All cars, Murray realized, had to become smaller and more efficient. He decided to apply what he had learned about building light body structures for racing cars to urban vehicles.

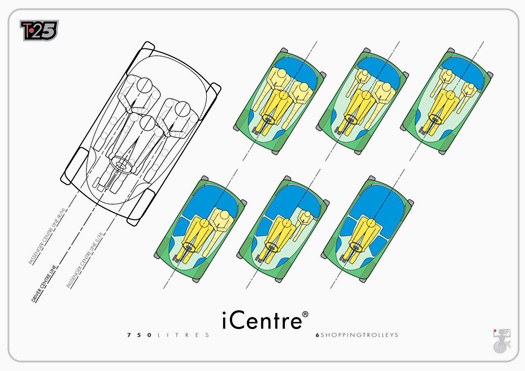

Seating is one of the lessons Murray adapted from the racetrack. His McLaren F1 has a single front seat with two, tighter passengers seats in the rear. The new car will offer six different seating options for up to three passengers, mixing adult and child seating and cargo space.

Six seating options are offered for a maximum of three passengers, with the driver in front.

Another adaptation involves materials: the McLaren F1 was the first carbon composite automobile sold commercially; its speed came from its light construction as much as from its powerful engine. The T.25 has a very light plastic body engineered for maximum economy and safety.

Murray has rethought almost everything. Forget doors, for instance. The T.25’s whole body tilts forward, like the hinged mask on a helmet, for easier access and reduced weight and cost. (This single door will remind some of the old BMW Isetta of the 1950s.) Murray has even redone the gas tank: it can be filled from either side.

Rather than doors, the T.25 features a hinged top piece that flips up.

The T.25 is about the greenest car around — except for its electric sibling, the T.27, which Murray began building last year after receiving a grant of 4.5 million pounds sterling from the Technology Strategy Board, a public/private outfit in the U.K. charged with pushing energy-efficient systems. For the T.27, Murray is teaming up with Zytek Automotive, a British firm, for the motor and battery. Its range will be about 62 miles.

What he has not discussed is the car’s price. That depends on the most mysterious aspect of Murray’s endeavor, his iStream production system. Murray claims iStream represents as revolutionary a departure in automotive manufacturing as did Henry Ford’s assembly line. But only a few experts have been shown the details — after signing nondisclosure agreements.

Murray claims that iStream will reduce factory size to a fifth of current plants and thereby decrease the investment cost of building and outfitting manufacturing facilities by 80 percent. Thanks to his car’s simple panel structure, gasoline and electric versions can be manufactured on the same assembly line, he says.

His business model is also unusual. Rather than trying to assemble capital to set up his own car company, he plans to license the design and production system to existing manufacturers.

Murray said that he aims for nothing less than to “create the next iconic city car,” in the tradition of the Fiat 500 of 1957 or the original Mini of 1959. If he can do that, even Ralph Lauren may buy one.