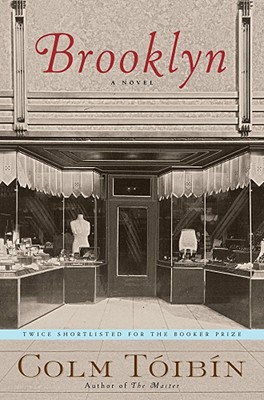

How could I resist when Colm Tibn, the Irish novelist who wrote one of my top ten books of the last ten years, The Master, came out with a new novel called Brooklyn? Set in Cobble Hill and Brooklyn Heights, no less. But it doesn’t start there, because in the years after the second World War, few Brooklynites were originally from Brooklyn. Instead we start in the smallest of small-minded towns in Ireland, Enniscorthy, where Eilis Lacey can’t get a job. She is smart and sweet, but options are limited and while she has no wanderlust, economics and the thwarted dreams of her older sister Rose launch her across the ocean to Brooklyn. In Brooklyn she works at a department store, one owned by Italians and located on today’s Fulton Mall. She lives in a rooming house on Clinton Street, where the morals of Eilis and her female housemates are closely watched by their landlady. She is desperately homesick, eventually saved by accounting classes and a young plumber named Tony. This summary sounds slight and even silly, and while ultimately I found the story small, particularly in contrast to the imagining of the life of Henry James in The Master, Tibn’s considering, considerate narration gives Eilis’s story (which must be the story of so many young women) weight.

Whether that weight is warranted, I am not sure. I hate not knowing what to think, and ambiguous endings always throw me off. I had to go back and read a few reviews of Brooklyn after I finished to gauge whether the ending was to be thought happy or sad. Reviewers seemed split, with more on the sad side. Without giving the plot away, I thought Eilis made the better choice, however unwillingly, so that sadness, and other reviewers’ sense that she had been trapped, made me sad. But I think my problem with the book, and my ultimate confusion, run deeper than the ending. As other reviewers’ also pointed out, Eilis is a passive heroine, with a very narrow view of the world. She is no explorer, and a terrible reader of people.

Tibn narrates the book from her occluded viewpoint, and this becomes more and more frustrating. We don’t know what to think of the priest who brings her over, her boss, her landlady, even Tony, because she doesn’t know, and in some scenes is shown to be wrong. To write as a nave Irish girl in the 1950s is a literary feat, but I am not sure it makes a good novel. Aside from the opacity of the characters except for Eilis, it also makes the book unsatisfying as a historical novel. Eilis rarely seems to look around her, describing only the counter in front of her, the kitchen at the boarding house, the hall at the church. I wanted to hear about the bustle of Fulton Street and the displays in the shop windows, the architecture along Clinton Street and the food at the coffee shop. Maybe Tibn didn’t want to do this research, or did it and discarded it, but the lack of visual description makes the book float above the place. To name it Brooklyn and then not give us Brooklyn is a mistake, and one that diminishes our interest in the story itself. Eilis isn’t really interesting enough to spend the time of even a short novel on, so without glimpses of her world, commentary from a knowing source, there’s no way to know if she would be happy in the new world.