Charles Saatchi’s new book, Beyond Belief: Racist, Sexist, Rude, Crude and Dishonest: The Golden Age of Madison Avenue is at once a breathtaking visual exposition of the nasty underbelly of advertising—and a hugely missed editorial opportunity.

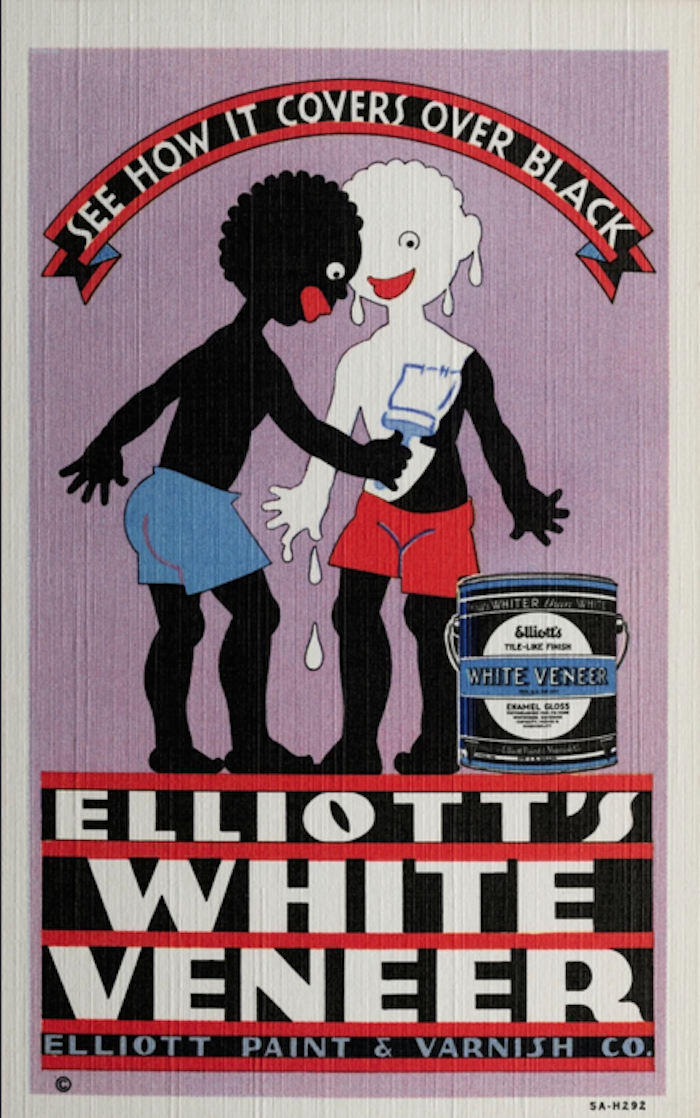

There is no question that the material gathered here is remarkable, particularly shocking because it’s so relatively recent. Readers will be mesmerized by many portions of this book, from physicians recommending cigarettes to their patients, to cigarettes themselves being marketed as a dietary aids, to children holding guns, women hung as taxidermy specimens, and dark (read “non-caucasian”) skin represented as dirty.

Iver Johnson Firearms ad, 1904

Elliot's Paint ad, 1930

Big and bold, brazen in their promise and hyperbolic in their claims, the ads themselves are at once mesmerizing and horrifying, begging the question: Was the accompanying text intentionally drafted to stay out of the way? Typographically, it reads like one long extended caption (set in oddly ragged and openly tracked narrow columns of Century Schoolbook) with essentially no attention given to an analysis of how these advertisements evolved over time. Did negative finger-pointing drive consumer spending? Did chauvinism frame market strategy? And how, frankly, did such black/white, male/female, clean/dirty binary opposition not incite reader revulsion, even as recently as the 1960s and ’70s?

Stunning imagery notwithstanding, a deep dive into social history would have been most welcome here. Did women buy cigarettes differently when shown drawings of infants recommending Marlboros? Did the fear of spinsterhood help motivate sales of feminine hygiene products, impact divorce statistics, erode the protective patina of public health warnings? As a history of material culture, the stories here are at once entertainingly comic and morally bankrupt, and the book would have benefited unquestionably from a more in-depth analysis of the social, cultural, and political infrastructure that corresponded to their evolution over time. Behold: the missed opportunity.

While the text is, to my knowledge, essentially accurate in a factual sense, the superficial commentary does little to counter the brutal nature of so much of this visual content. Even Edna Murphey’s “Odorono” campaign, one of the more mild examples in this volume, contains a rich and compelling provenance that is not shared here. A comparatively early serial entrepreneur, she did indeed peddle antiperspirants at the 1912 World’s Fair in Atlantic City, but took the reigns at a company that, among other things, would later introduce colored nail polish to American women. (Murphey sold that company and later built an herbal empire that she would sell, in the 1950s, to McCormick spices.)

Odorono ad

The story of Murphy—who later became Mrs. Ezra Winter (her second husband was an accomplished American muralist)—would have offered a fascinating counter to what is, in a sense, a visual record of the modern, marginalized woman, here shown as a doormat and a broomstick, hugging a vacuum cleaner, imprisoned by her kitchen—the species itself represented as decorative, if inert appendages of the products they’re mindlessly recruited to endorse. Indeed, viewers who devotedly watched all seven seasons of Mad Men (a sizable demographic) will likewise be disappointed by the scarcity of written content devoted to the agencies responsible for many of these disturbing advertisements. (Another missed opportunity.)

At a moment in cultural history that is likely to be remembered for its increased appetite for all things visual, but perhaps equally for its (mercifully) increased awareness of the pernicious reach of public bigotry, contemporary audiences will recoil from these images with shock and disgust. Regrettably, without an accompanying text to make sense of it all, this book serves as little more than a freak show.