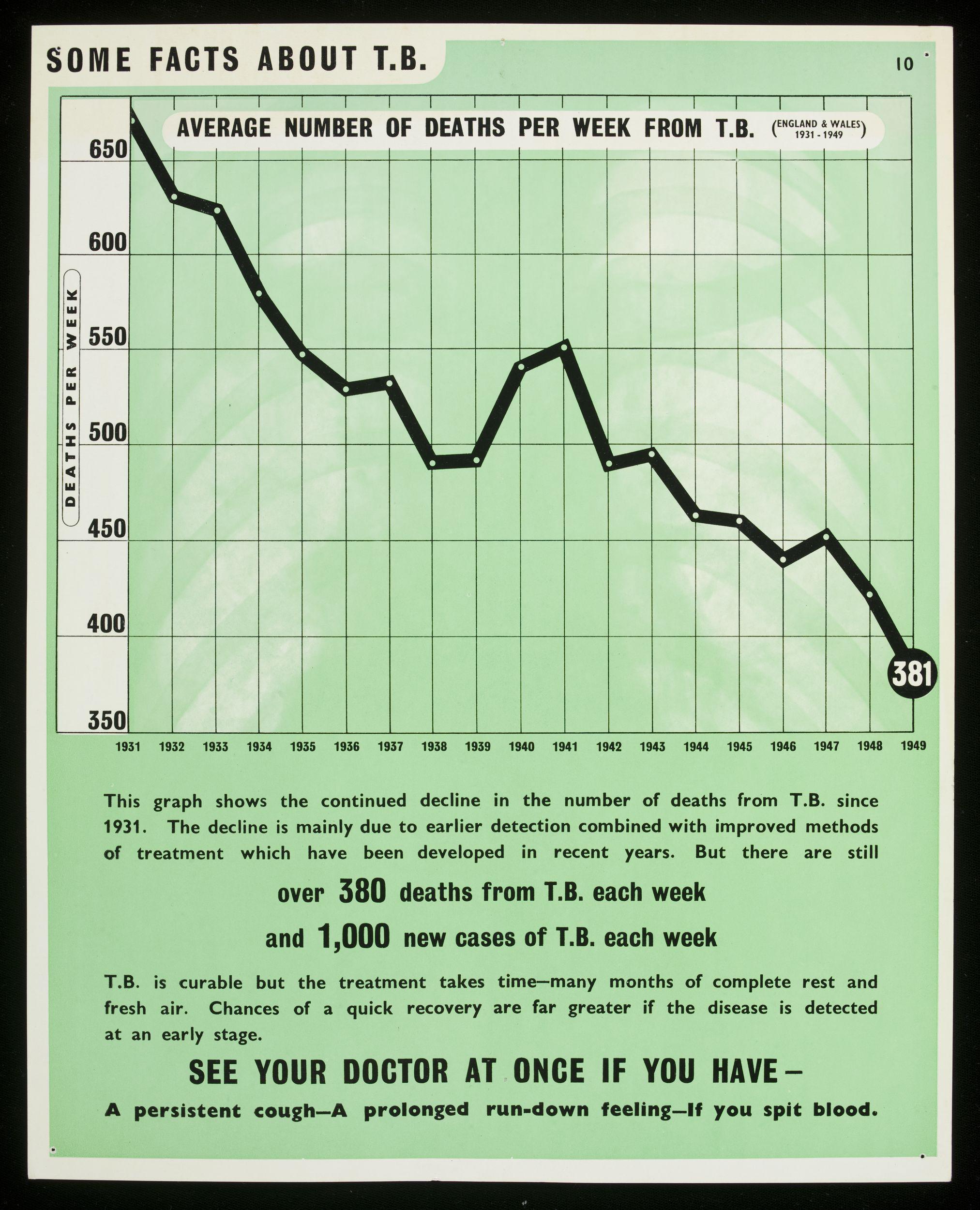

Some facts about TB. Colour lithograph issued by the Ministry of Health, ca. 1949. Credit: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The 1918 flu pandemic has become the choice historical marker many are using to orient themselves within our new, turbulent reality. However, from the standpoint of design history, the fight against tuberculosis may be a better parallel—particularly in terms of how global, collective action is necessary to overcome disease.

Tuberculosis (TB) has been around since antiquity and continues to infect millions today. Though Robert Koch’s 1882 revelation that TB is spread by bacteria (previously, people thought it a hereditary disease), his discovery caused a societal backlash. Fear of contagion amongst communities was rampant, and people were especially discriminatory against the urban poor. Exacerbating the issue, in the 1880s, Dr Edward Livingston Trudeau promoted the self-isolation of TB patients as a way to protect both the healthy and the sick, which further perpetuated the stigma against those suffering from TB. Yet, new “sanatoriums” also coincided with the rise of organisations dedicated to researching and educating the public about the illness.

In the twentieth century, many of these organisations created posters to warn people about the dangers of contracting TB, as well as how to protect themselves through preventative medicine. These posters exemplify how public art, in collaboration with health officials, can triangulate tone, content, and imagery to succinctly deliver critical information to the masses. Earlier examples equate TB to common phobias and appeal to viewers’ sense of fear, whereas later designs become more centred around medicinal themes such as causes, treatments, and the need for a unified public response. One of the most remarkable aspects of these posters is that they can found worldwide. Tuberculosis wasn’t just an “American” disease or an “Italian” disease or a “Chinese” disease—it affected communities across the globe, as these designs testify.

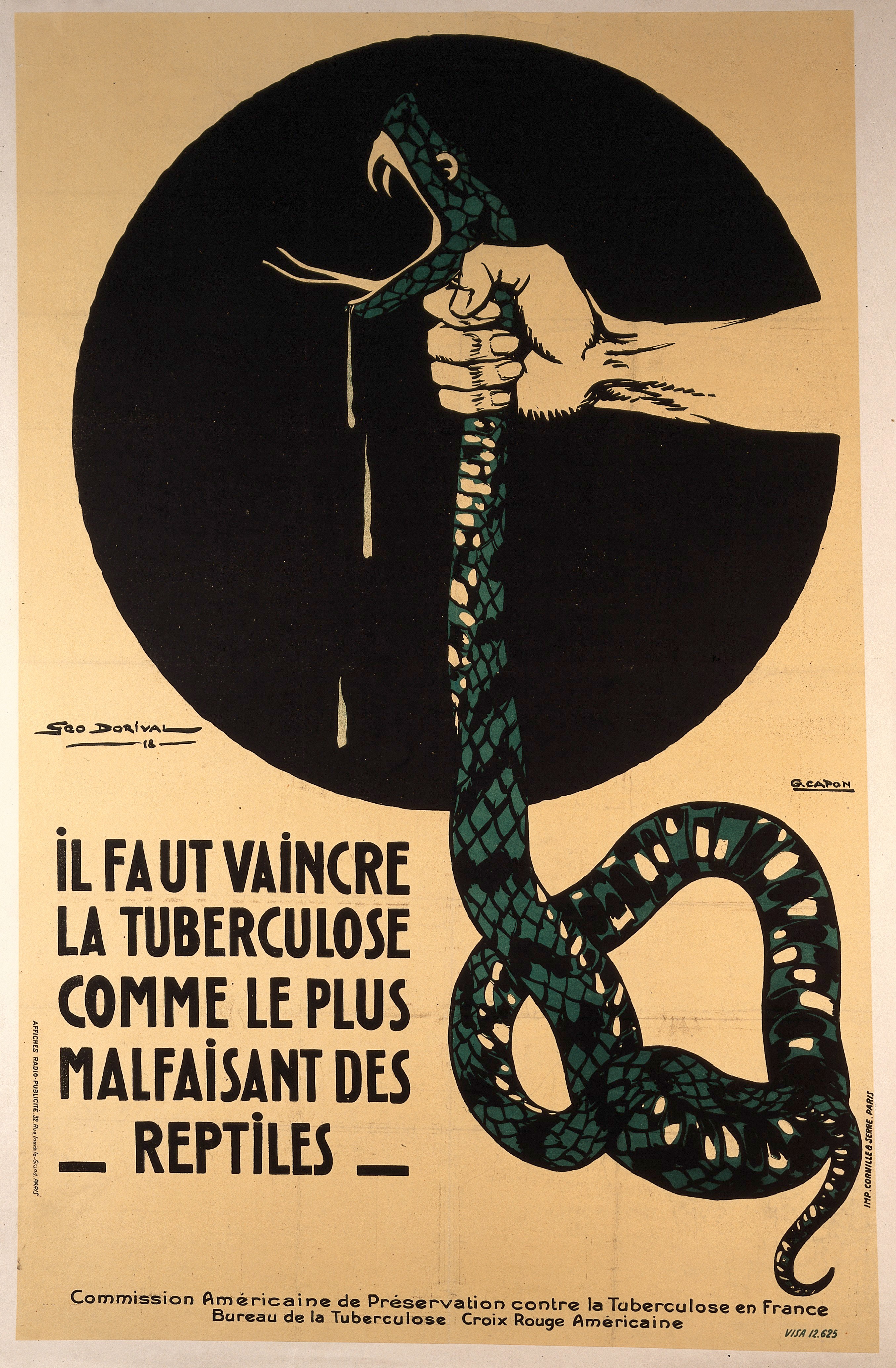

The strangling of a poisonous snake, representing the crushing of tuberculosis. Colour lithograph after G. Dorival and G. Capon, ca. 1918. Credit: Wellcome Library no. 47641i.

In 1917, the director of public hygiene in France accepted American aid to help manage the spread of tuberculosis in his country. The American Red Cross and the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation quickly began their work, issuing posters like this one that equated TB to a deadly serpent that “must be vanquished.”

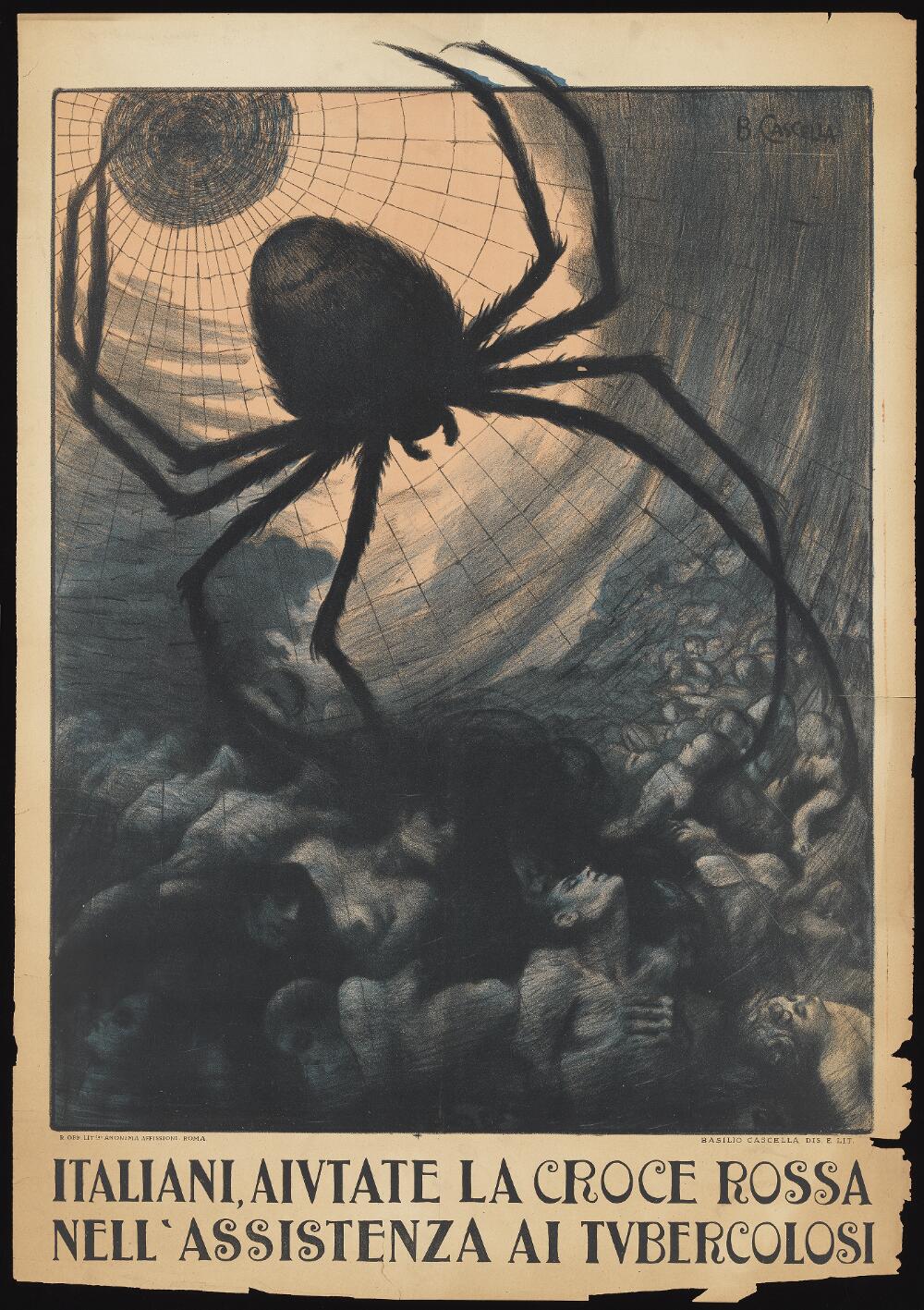

A giant spider catching crowds of humans in its web; representing tuberculosis. Colour lithograph by B. Cascella, ca. 1920. Credit: Wellcome Library no. 575580i.

Around the same time, this poster was released by the Italian Red Cross where tuberculosis was once again personified as a menacing creature. A black, hairy spider creeps in from the top edge of the frame and its thin arms reach down into the mass of huddled people below, who appear as pale, suffering phantoms.

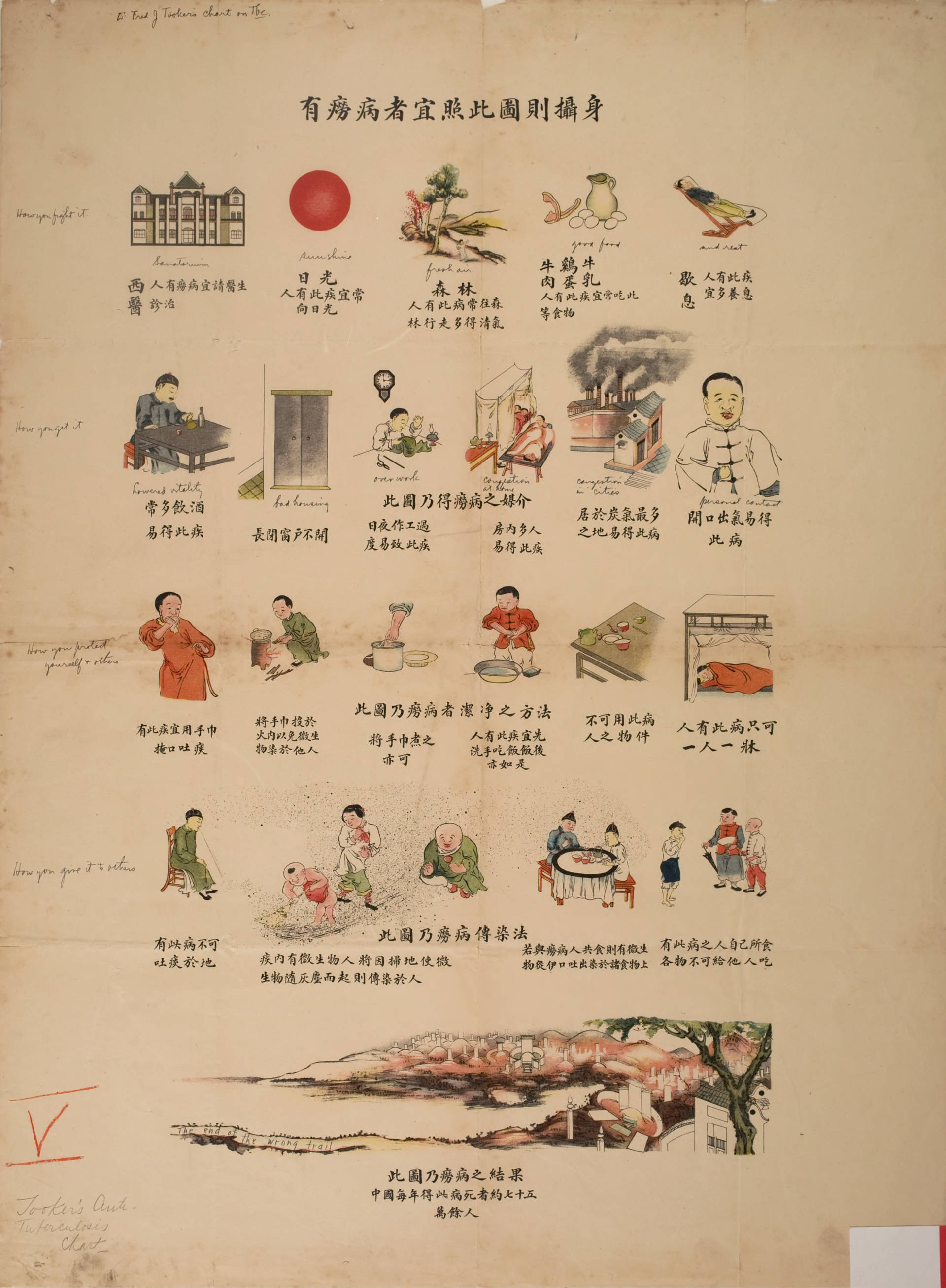

Dr. Frederick J. Tooker’s Anti-Tuberculosis Chart. First half of the 20th century. Credit: University of Minnesota Libraries, Kautz Family YMCA Archives, ymca182962.

This detailed chart by Dr Frederick J. Tooker, who was an American medical missionary in Hunan, China, describes how to prevent the spread of tuberculosis, the disease’s causes, and its treatment. Illustrations of “good food”, “sunshine”, and vignettes of best and worst practices are accompanied by Chinese captions. The depiction of a cemetery at the bottom is labelled with the dire warning, “This shows the result of tuberculosis—More than seven hundred and fifty thousand people die from this disease every year in China.”

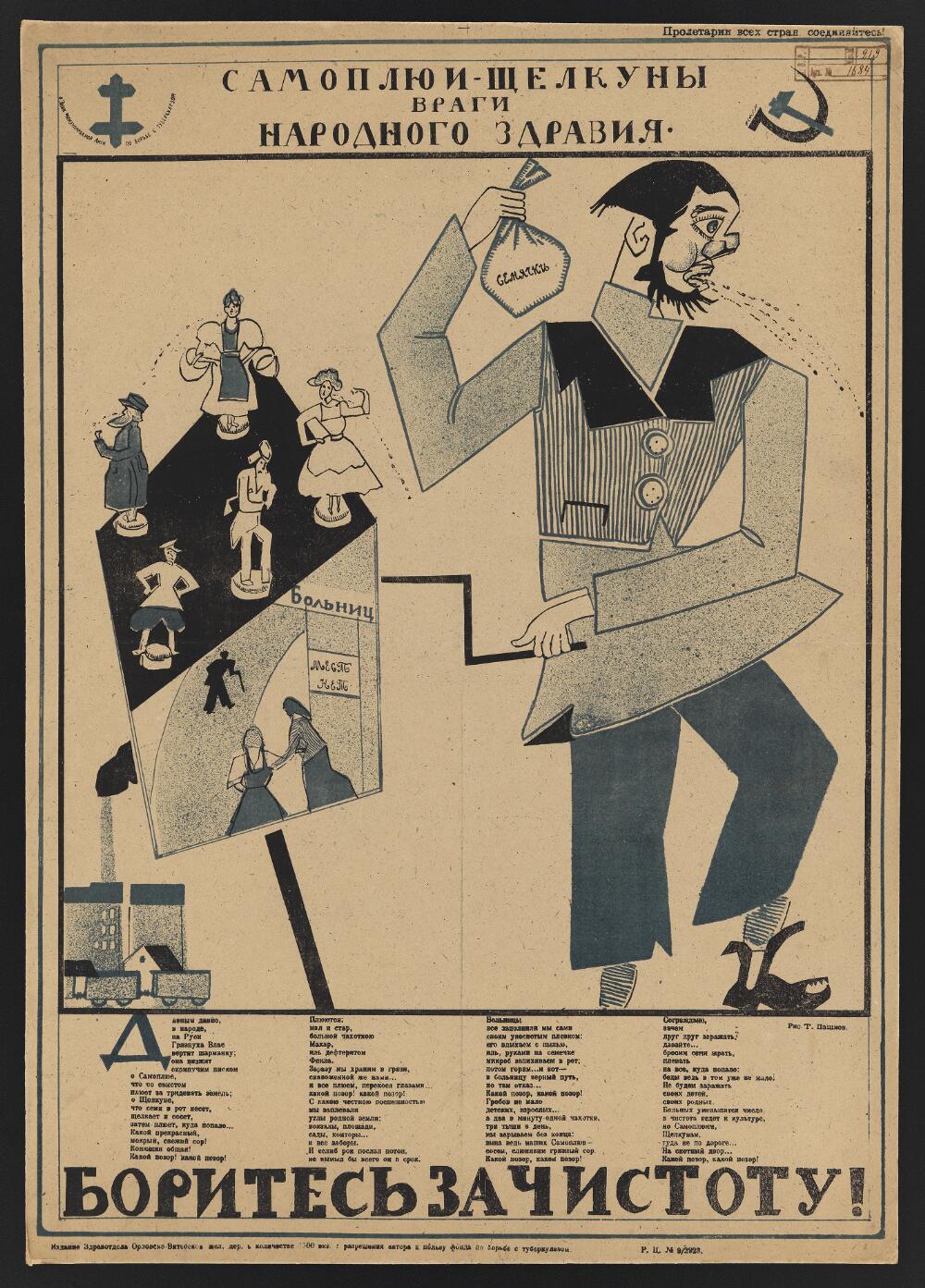

Dirty Vlas the organ-grinder demonstrating that people who spit or crack sunflower-seeds spread tuberculosis and are therefore enemies of the people's health. Colour lithograph by T. Pashkov, ca. 1920-9. Credit: Wellcome Library no. 545730i

Spitting was one of the ways tuberculosis spread and this poster depicts an organ grinder named “Dirty Vlas” who evidently revels in expectorating sunflower seeds. Likewise, the figures on his instrument are also shown spitting and stand somewhat presciently above a scene showing the entrance to a hospital. The text at the bottom of the poster tells the story of two people, called Natural Spitter and Seed Cracker, who “devour with relish sunflower seeds, and spit the rest out on to the street…which generates germs and causes people to die, of diphtheria and tuberculosis”.

March on to health Get your test now: City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium. Photograph by the Chicago WPA Federal Art Project, between 1936-9. Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division no. 98508416.

Between 1936 and 1943, over 35,000 poster designs were created by artists employed by the Federal Art Project which was sponsored by the United States Works Progress Administration as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal. These posters advertised public programs, including those aimed at improving health. This poster, created by the Chicago division of the project, encourages citizens to get tested for TB using rather militant imagery. The line of men and women marching along in unison emphasises the need for a synchronous, collective response to fight the disease.

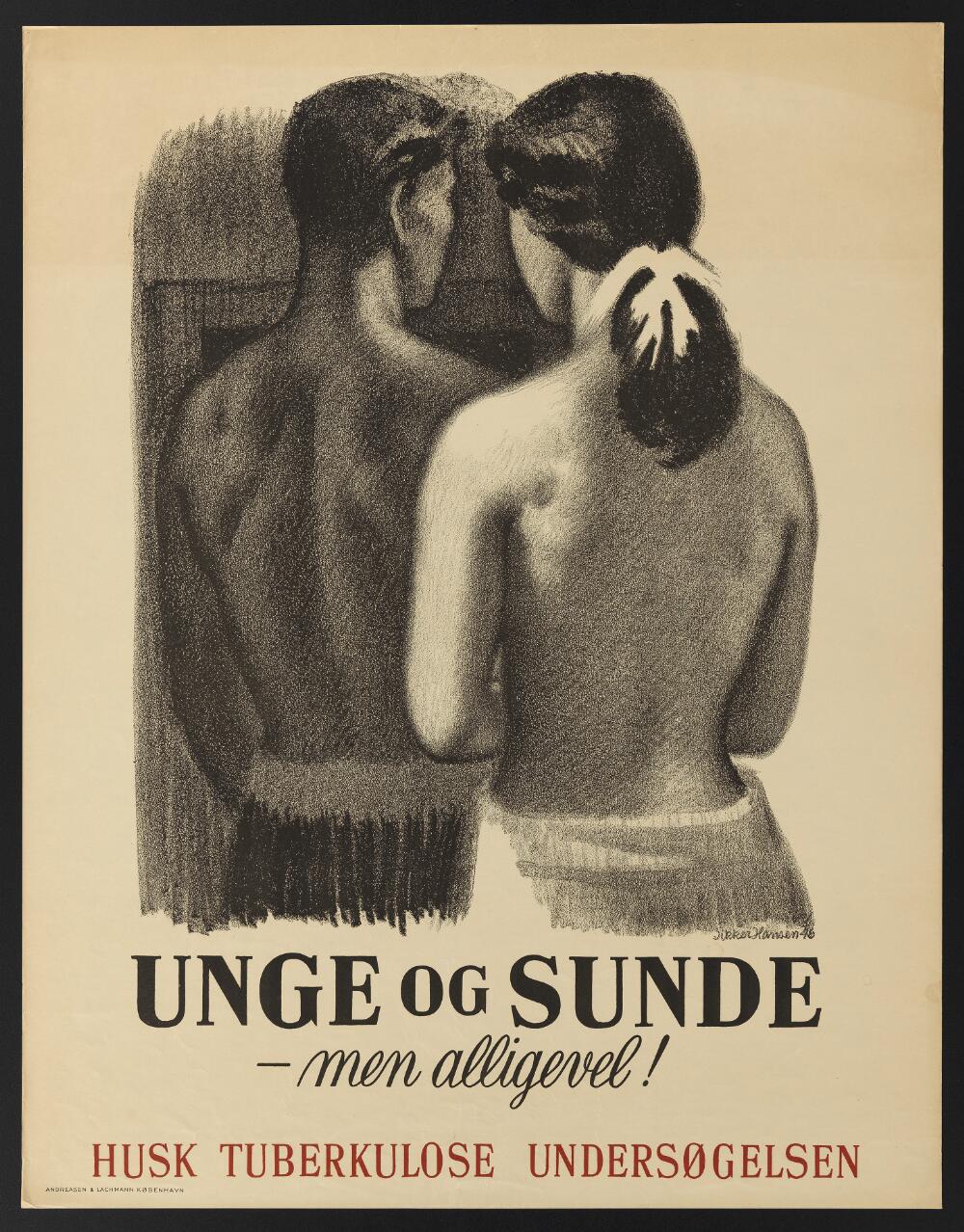

A young man and young woman who appear to be healthy, but may have latent tuberculosis; representing the need of a checkup for detection of tuberculosis. Colour lithograph by S. Hansen, ca. 1946. Credit: Wellcome Library no. 660215i.

The soft, poignant illustration of a young man and woman in this Danish poster is complicated by the text below which reads, “Young and Healthy/ Yet/ Remember the Tuberculosis examination.” The viewer’s initial reaction to the otherwise healthy figures would have mirrored the confusion of individuals infected with latent TB, which is asymptomatic.

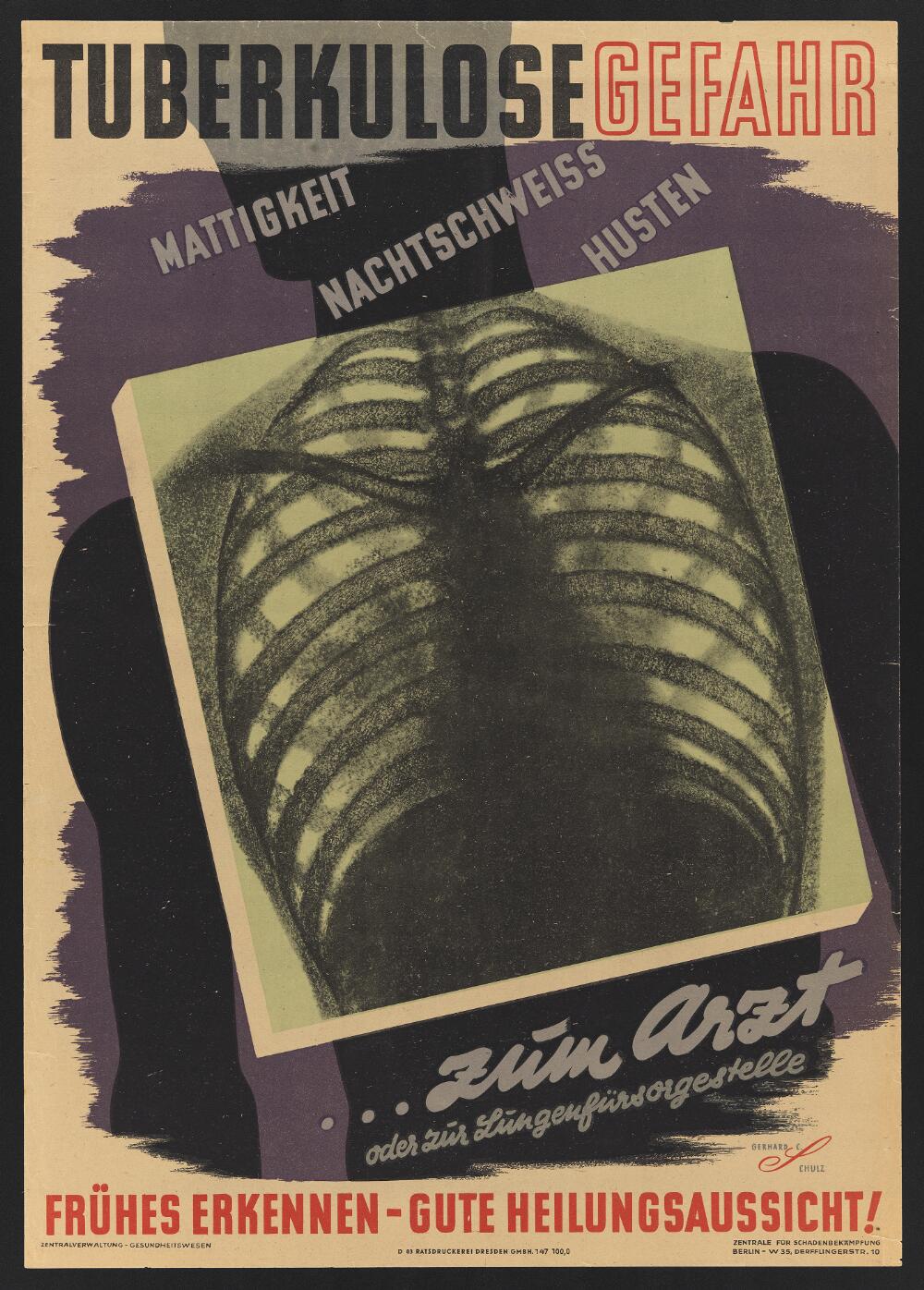

A radiograph of the chest; representing the need for early detection of pulmonary tuberculosis. Colour lithograph by G.C. Schulz, ca. 1947. Credit: Wellcome Library no. 660212i.

This East German poster returns to the fear-mongering tactics of the earlier designs. However, rather than personifying TB as a beast, the text imparts the frightening symptoms of tuberculosis, “weariness, night sweats, coughing” with the warning, “You can go to the doctor—or you can have that!” The image of a rib cage locates the region of the disease as well one of its cures: early detection by chest x-rays.

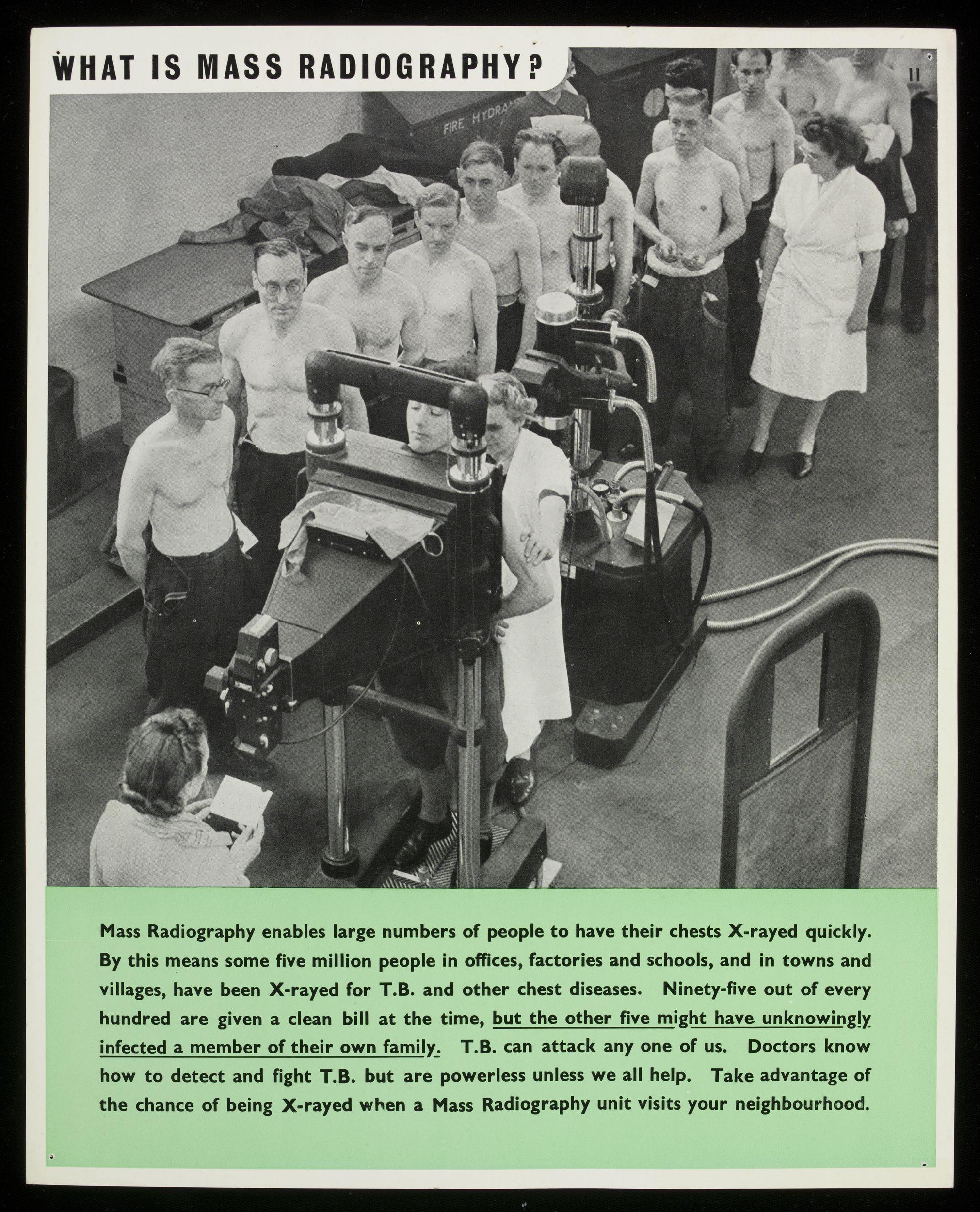

What is mass radiography? Colour lithograph issued by the Ministry of Health, ca. 1949. Credit: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

After the establishment of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948, there was a rise in the United Kingdom’s large-scale public health interventions. To screen for tuberculosis, the Ministry of Health implemented a mass radiography programme that allowed for large numbers of people to be tested, thereby helping to identify and contain the disease. The caption, “TB can attack any one of us,” along with photographic illustrations and raw data, democratises the illness and delegitimises the claim that TB was only a poor person’s disease. An individual’s responsibility to their whole community is further emphasised by the statement, “Doctors know how to detect and fight T.B. but are powerless unless we all help.”

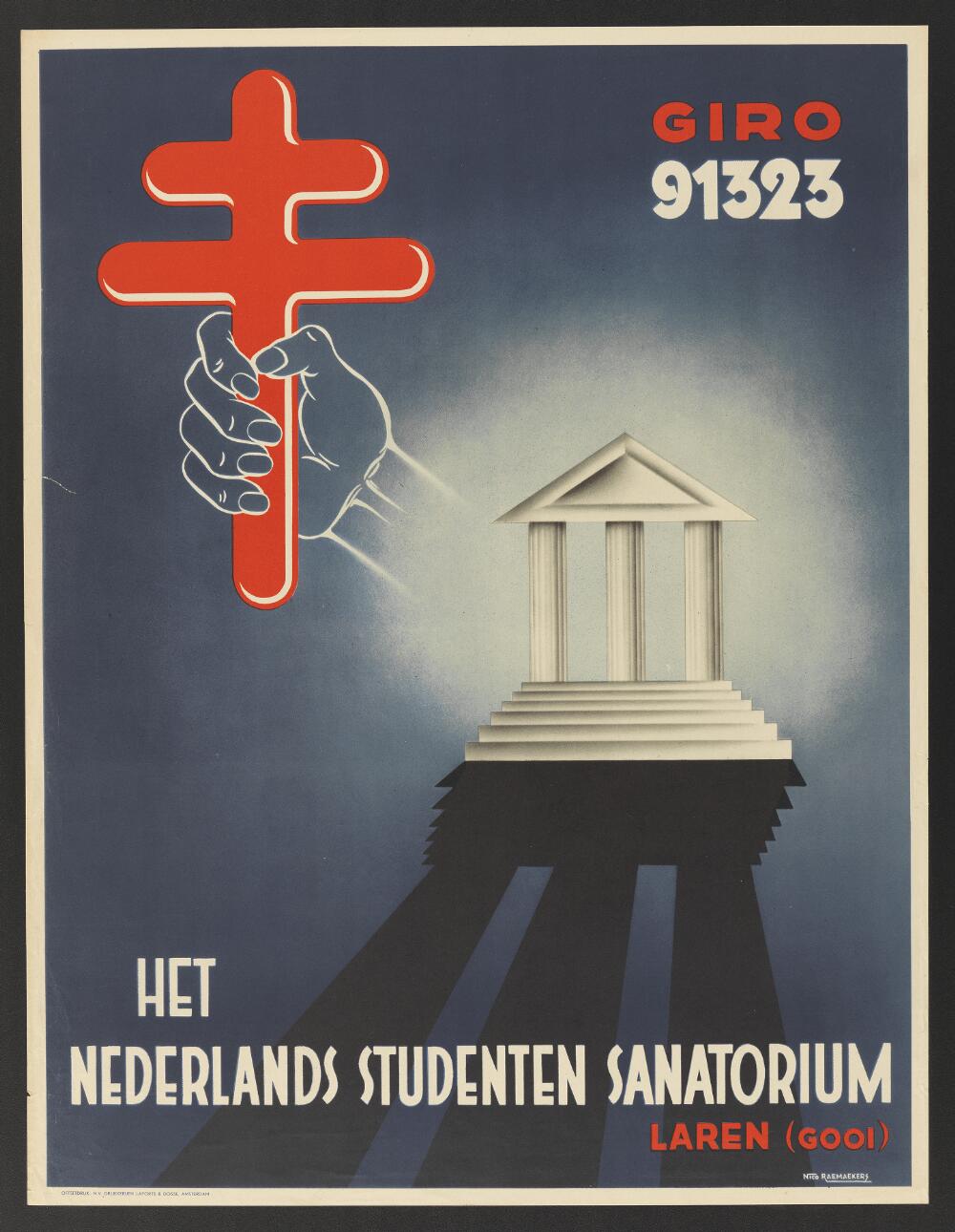

A portico and the cross of Godfrey of Bouillon; representing academia and tuberculosis, as the elements of the sanatorium for students in the Netherlands. Lithograph by N. Raemaekers, ca. 1950-1. Credit: Wellcome Library no. 995818i.

For scholars at the Nederlands Studenten Sanatorium in Laren, being ill did not mean that one’s studies had to cease. The sanatorium opened in 1947 and housed patients who wished to continue their academic work, while also allowing time for arts, recreation, and healing. The image of a Greek facade, referencing classical-style university architecture, symbolises what students were still able the pursue while at the sanatorium. The double-barred cross being thrust forward was the logo used by The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease until 2002. Originally the standard of Godfrey of Bouillon during the first crusades, Dr Gilbert Sersiron suggested the cross as the organisation’s logo in 1902 because it symbolised the world’s “crusade” against TB.

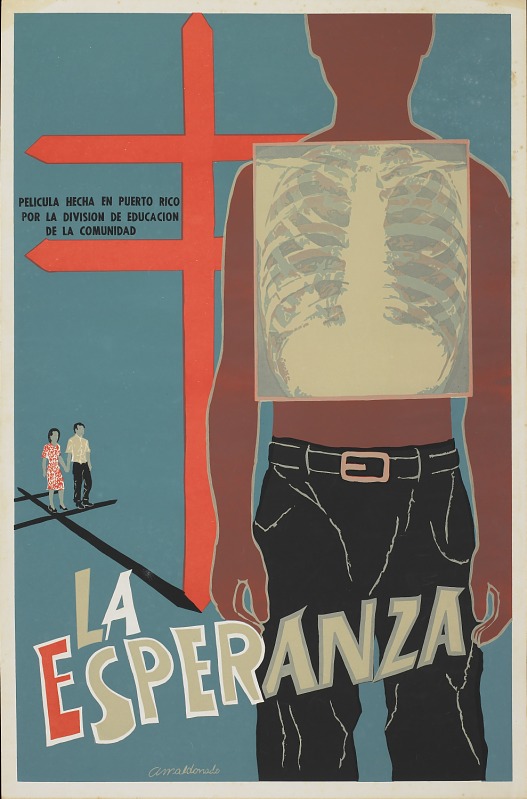

La Esperanza. Screenprint by Antonio Maldonado, ca.1964. Credit: Puerto Rico Division of Community Education Poster Collection, 1940-1990, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

This poster advertises a film titled “Hope” which was released by the Puerto Rico Division of Community Education in 1964 to inform people about how they could protect themselves and their neighbours against tuberculosis. Though the poster addresses a global illness, the vernacular illustration and bouncy block lettering shows how regional styles can influence the design, thereby appealing to local communities. Though tuberculosis infections began to greatly decline by the 1960s, it still impacted—and continues to disproportionately affect—people in areas without robust health services.

In 1946, the development of an antibiotic began to eradicate the spectre of tuberculosis from daily life, at least in the West. Three months ago, it would have been difficult to imagine living under the fear of contracting such a deadly, miasmic disease. Now, it’s quite easy.

Some of us are coping with the current situation by drawing historical parallels. We look to the past for stability—to find solace in the notion that the human experience is an iterative one. However, there is a caveat to this. I was listening recently to an interview with the Civil War historian David Blight who rightly noted that “History doesn’t save us, but it prepares us.”

It is up to us, in the now, to save our communities. And not just our neighbours down the street, but by reaching across borders to provide aid to those most vulnerable and desperately in need. In the act of saving, we create something stable for succeeding historians, epidemiologists, and people simply trying to better understand their lives, to look to in their future present.