Peter Seitz in the design studio at the Walker Art Center, circa 1965

Peter Seitz: b. 1931

Peter Seitz is a German born graphic designer who was responsible for bringing the ideas and ideals of European Modernism to the Upper Midwest in the 1960s. After studying design at Ulm Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) and Yale University, he was appointed Design Curator at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Seitz is best known for his interdisciplinary approach to design and his award winning corporate identity programs. He also taught at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD). Seitz was the first Minnesotan to receive the AIGA Fellow Award in 2000.

Early Life

Peter Seitz was born on August 15, 1931 in Schwabmünchen, Germany, a small town near Augsburg. The second of four sons, his mother, Olga (Kirschenhofer), was a homemaker, and his father Georg, worked at the local brewery Hansenbrau (Rabbit Brew). When he wasn’t drawing, painting or doing chores, Seitz read adventure stories. His early interest in the United States was piqued by the Wild West novels by German author Karl May.

During World War II, Seitz’s father was drafted into the German army and stationed at a nearby airstrip. In 1945, Schwabmünchen was bombed. The bombing raid killed 60 people and injured 220 others. It also destroyed many buildings including the local high school Seitz attended. Because Seitz’s parents couldn’t afford to send him away to school, Seitz was apprenticed to a local master painter Luipold Gogl. From Gogl, Seitz learned to paint wood and imitate hardwood grain patterns with precision. He also took professional painting classes twice a month in Augsburg where he excelled in hand lettering and painting decorative Germanic motifs. He became a journeyman painter and continued to work for Herr Gogl for five years.

In 1953, Seitz was introduced to a talented graphic designer who had graduated from the Kunstschule der Stadt Augsburg (Augsburg School of Art). When he saw this designer’s work for the Augsburg Opera House, Seitz decided to become a graphic designer. In 1954, at age 23, Seitz began studying design at the Augsburg School of Art. Eugene Nerdinger, director of the graphic arts department, and noted author and calligrapher, was so impressed with Seitz’s work ethic and design skills that he recommended him for a job as a salesman and production artist at a local textile engraving company. This job helped Seitz to expand his knowledge of the graphic arts, especially printing, and to learn more about possible career options while continuing his studies.

Ulm HfG and Yale University

The Ulm Hochschule für Gestaltung (Ulm University of Design, HfG) opened in 1954. HfG was modeled after the Bauhaus, which was shut down by the Nazis in 1933. Designed by the Swiss architect Max Bill, Ulm was dedicated to two resistance fighters who were executed for printing anti-Nazi pamphlets and posters.

An interdisciplinary approach to design was at the heart of the Ulm curriculum. The three main departments — architecture, communication design and product design — collaborated on a variety of projects. [1]

Early in the summer of 1955, on a Sunday morning, Seitz’s mother Olga showed him an article in the Schwabmünchen newspaper about Ulm and its beautiful new campus. This glowing article inspired Seitz to ride his bicycle 60 miles to Ulm to apply for admission. He was accepted as a first year student and lived in the student dormitory. For the first time in his life Seitz had hot running water available day and night. The thrill of taking a hot shower whenever he wanted was one of the highlights of his first year.

All 30 of the first year students were enrolled in the Foundation Course, which was a year of basic design studies. The students also studied psychology, sociology, behavioral science, and marketing as it related to design. Seitz recalls that, “We were taught that design is not frivolous. It is serious. Good design is very serious.” [2] Argentine designer Tomás Maldonado, Seitz’s foundation teacher, became one of his mentors and was the first person to encourage him to consider a teaching career.

While at Ulm, Seitz was taught that designers have a responsibility to take an active role in society. The school advocated an objective and socially aware approach to design. Having personally witnessed the devastation of Europe during World War II, Seitz came to believe that designers can solve social as well as aesthetic and utilitarian problems. In 1956, Seitz met John Lottes, an American student from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD), who was studying at Ulm on a Fulbright Scholarship. Seitz practiced speaking English with Lottes and learned as much as he could about America. For the first time, he seriously considered studying or working in the United States. At the same time, Otl Aicher, another of Seitz’s design teachers, hired Seitz to work in his design studio and became his most influential mentor.

Aicher, who had just returned from six weeks of teaching and lecturing at Yale University, encouraged Seitz to apply to the School of Art graduate program. In 1958, Peter was accepted as a graduate student at Yale University’s School of Art. He was also awarded a $250 Fulbright Travel Grant from the American Women’s Club at the Stuttgart Army Base. Seitz recalls, “In those days $250 was a princely sum. It was all the money I had when I came to America.” [3] In 1959, at age 28, Seitz completed his senior thesis (a corporate identity for Hubert Fisheries in Hamburg, Germany) and graduated from Ulm with a Bachelor’s degree in Visual Communication. With the assistance of Walter Zeischegg, a product design teacher at Ulm, who arranged free passage for Peter on a Danish freighter from Hamburg to Montreal, Seitz arrived at Yale two days after the fall semester started, exhausted and overwhelmed from the journey. Seitz’s immediate concern was that he had arrived at Yale late;

“For a German to be late for school was an unthinkable transgression. I was afraid they would send me back home. But this turned out to be a blessed time period. The head of the design department arranged for me to stay in a free room at the International Center. My roommate was a law student from Cambridge, England. He helped me to speak English correctly and was very kind.” [4]

At Yale, Seitz studied with such celebrated graphic designers as Paul Rand and Bradbury Thompson. He also studied photography with the Swiss designer Herbert Matter. In the spring of 1961, Seitz completed his thesis (a series of theater posters) and received his Master’s of Fine Arts degree in Graphic Design and Photography from Yale University.

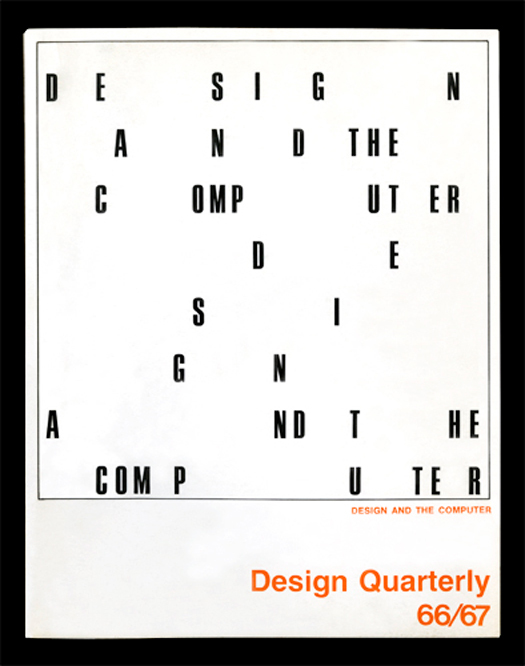

Design Quarterly 66/67: Design and the Computer (cover), 1966, Walker Art Center

After graduation, Seitz worked for the architectural firm, I.M. Pei & Associates in New York City and taught at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). In 1964, Martin Friedman, director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, appointed Seitz design curator and editor of Design Quarterly. At the Walker, Seitz curated the exhibitions Toward a New City (1965), Norman Ives, Graphic Design (1966), Furniture by Breuer/Le Corbusier/Mies van der Rohe, 1924–1931 (1966) and Mass Transit: Problem and Promise (1968).

The close relationship between design, science, and technology that was emphasized during Seitz’s studies at Ulm, led him to apply this concept to his work at the Walker, where he was one of the first design professionals to make the connection between emerging computer technology and its application to graphic design. In 1967, he designed and edited a landmark double-issue of Design Quarterly 66/67 that featured the topic “Design and the Computer.” It was the first time the idea of using the computer as a design tool was discussed in a national design journal.

In 1968, the Walker Art Center closed temporarily for construction and Seitz left to start his own graphic design business. That year he placed the very first listing for a graphic designer in the Twin Cities Yellow Pages. In 1970, Seitz (graphic design), Dewey Thorbeck and Al French (architecture), Roger Martin (landscape architecture), and Steve Kahn (computer specialist) launched InterDesign, the Twin Cities’ first interdisciplinary design firm. This new firm was groundbreaking in its collaborative philosophy and interdisciplinary approach to design.

The firm’s major projects included the identity programs and signage systems for the Minneapolis parkways, the downtown St. Paul skyways, the Minnesota State Capital and the Minnesota Zoological Gardens. The first Print Casebook series featured the signage system InterDesign developed for the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

In 1978, Seitz left InterDesign to start a new design firm called Seitz Graphic Direction. It included former InterDesign senior graphic designer Hideki Yamamoto and other members of the firm’s graphic design department. After two years, the name of the firm changed to Seitz Yamamoto Moss. The firm specialized in corporate identity projects. Major clients included: Lutheran Brotherhood, Control Data, Miracle Ear, the Minneapolis Convention Center, Edina’s Centennial Lakes Retail Area, the Mayo Clinic, and the Pacific Convention and Exhibition Center in Yokohama, Japan.

Modular exhibition system and exhibition design, 1973 Minnesota State Art Council

Minneapolis College of Art and Design

In 1971, while working full-time as a partner at InterDesign, Seitz was hired by the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) to teach the third-year graphic design class. Although it was a logistical challenge, he strongly believed that it was important for practicing designers to teach students the concepts and skills necessary to excel in the graphic design profession. Seitz introduced his students to the rigorous discipline and formal harmony of modern design. He emphasized the value of good design and how it influences the way average people are informed.

Starting in 1981, Seitz spent three years setting up a computer laboratory at MCAD. He used his business contacts to secure donations for expensive systems that the school could not afford to buy. The lab contained a few Apple computers, a brand new Macintosh, and other small machines that were used to introduce students to basic computer capabilities in one room; and three professional grade “dedicated” computer graphics systems (a Dicomed D-38 system, a Florida Computer Graphics system, and a 3M BFA “Paint System”) for advanced students in a second room.

Seitz retired from teaching at MCAD in 2002. Reflecting back on his thirty- year career, he said, “I’m sorry to say that I used to be a terrifying teacher. Too often I was unnecessarily harsh. However, my intensity was based on my belief that design was a serious business and my students must be serious about their studies if they were to succeed. I am still a modernist at heart, but I now know that there is more than one way to create good design. You might say that I’m a recovering perfectionist.” [5]

Minnesota Graphic Design Association and AIGA Minnesota

Seitz’s dedication to graphic design excellence also was reflected by his long-standing involvement in the graphic design profession. When a young Minneapolis designer, Tim Larsen, started making phone calls to create a list of graphic designers to influence the design of a new license plate by the State of Minnesota in 1976, Seitz agreed to lend his name to the list if Larsen agreed to start a professional graphic design organization. This organization, the Minnesota Graphic Designers Association (MGDA), was the predecessor of AIGA Minnesota, which was established in 1988.

Advocating the value of good design was Seitz’s passion. He helped draft the MGDA’s Charter and served as its president in 1978-1979. He was a national board member of AIGA from 1983-1986, and has represented the Midwest for the Society of Environmental Graphic Designers (SEGD).

Seitz was the first Minnesotan to receive the AIGA Fellow Award in 2000. This award recognizes mature designers who have made a significant contribution to raising the standards of excellence in practice and conduct within the design community.

Peter Seitz’s story is about how one individual affected the lives of so many while improving the visual environment of the Twin Cities. The ideas and ideals of modernism that Seitz planted in the rich cultural soil of Minnesota have flourished, setting the standard for quality design in the Twin Cities — something that we have come to expect and now take for granted. Seitz’s advocacy of the principle that “good design is good business” has helped create local, national, and global respect for the social and economic value of excellent design. That is his legacy.

Notes

1. Lindinger, Herbert. Ed. Ulm Design: The Morality of Objects. MIT Press: Boston. 1991. 124-129.

2. All quotes are from interviews with Peter Seitz conducted by Kolean Pitner and Bruce Wright from April 2002 to March 2003. They are included in Peter Seitz: Designing a Life, Blauvelt, Andrew. Ed., MCAD: Minneapolis. 2007.

3. ibid

4. ibid

5. ibid